I’ve been thinking about the growing tension between America’s gas ambitions and the actual hardware needed to move those molecules. Everyone talks about record U.S. production, surging LNG exports, and gas-powered data centers. But the real bottleneck — the thing that determines how fast we can grow — comes down to miles of steel in the ground. That’s why the pace, politics, and practicality of U.S. natural gas pipeline development deserve a closer look.

Let’s start with the Constitution Pipeline. It was proposed to deliver 650,000 dekatherms per day of Marcellus gas from Pennsylvania to the Iroquois and Tennessee Gas Pipeline systems, aiming to supply New York and New England. The project was cancelled in 2020 after the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation denied a key water permit, despite it having FERC approval. But with New England still importing LNG at prices often several times Henry Hub during winter peaks, quiet talk of reviving similar routes is resurfacing. Recently, Donald Trump and New York Governor Kathy Hochul discussed the possibility of reviving the Constitution Pipeline or similar infrastructure, though no formal agreement has been reached yet. Talks are ongoing, and while no new permit is on file, the policy window is clearly reopening. This is a classic case where economics aren’t the constraint; permitting and politics are.

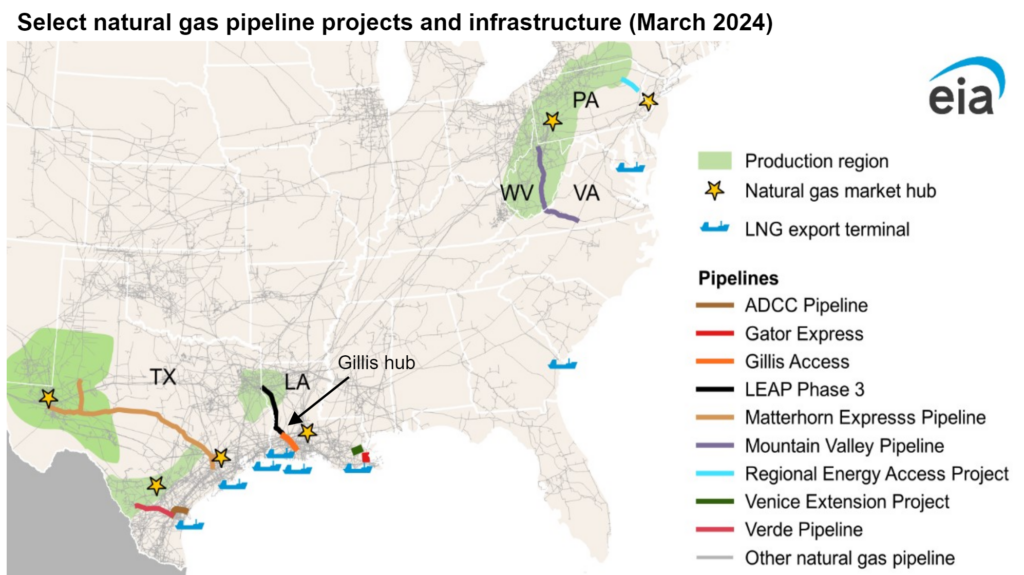

Shifting to another critical corridor: the Transcontinental Gas Pipeline (Transco), which is owned and operated by Williams. This massive interstate system is central to East Coast gas supply and is undergoing major expansion. Williams’ Southeast Supply Enhancement (SEE) project is slated to add 1.6 Bcf/d of capacity by 2027, boosting flows from Pennsylvania to Georgia and the Carolinas. The project is currently in development, with Williams initiating the pre-filing process with FERC in early 2024. Separately, the company has also greenlit its Texas to Louisiana Energy Pathway (TLEP), aimed at expanding capacity between the Haynesville and Gulf Coast LNG terminals. Such positive developments signify the need for more pipeline infrastructure and also the fact that policymakers and industries are already focusing on it.

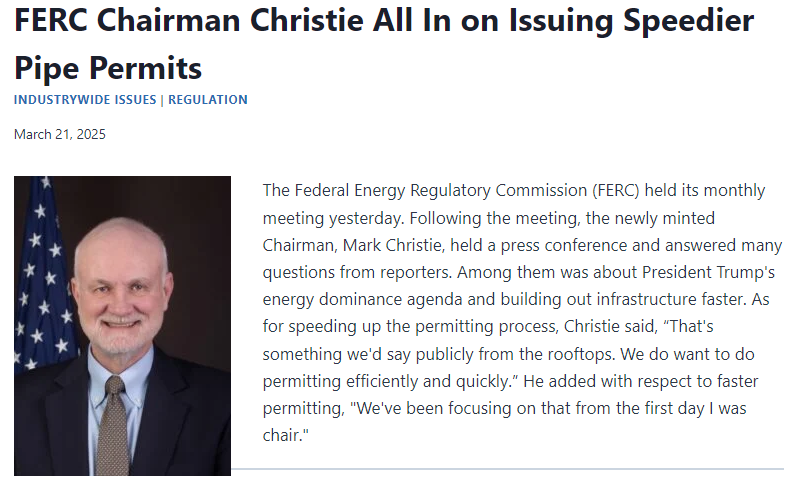

These expansions reflect more than just commercial opportunity — they’re becoming essential to grid stability, a point underscored recently by federal regulators. FERC Chairman Mark Christie has been direct. In February 2025 remarks, he said: “Electric reliability depends on gas reliability”, linking the fate of the power grid to timely gas pipeline buildout. His warning came as more coal and nuclear units retire, and gas picks up the baseload slack. Add AI-driven data center growth and industrial reshoring, and pipeline lag becomes a systemic grid constraint. Few days ago, he categorically supported issuing speedier pipeline permits.

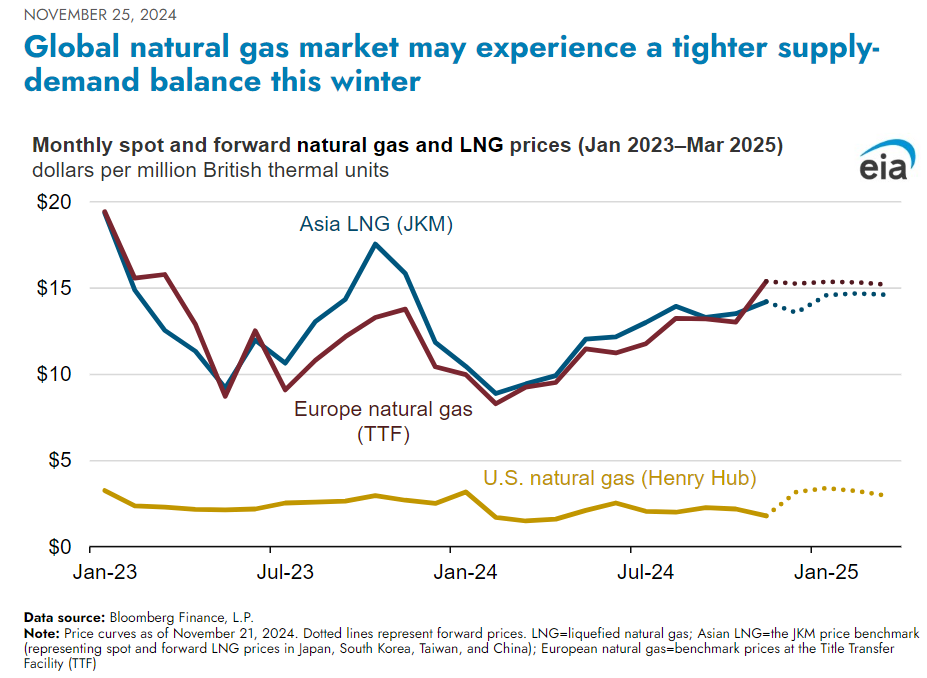

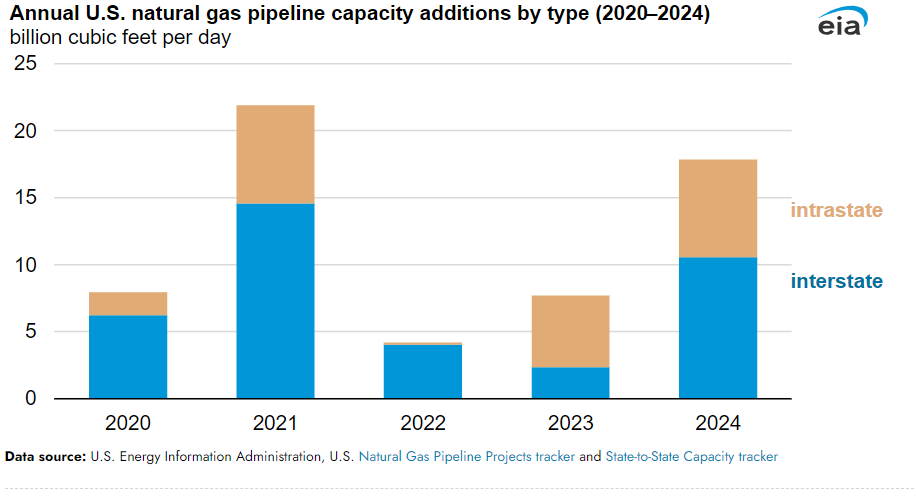

Similarly, in Louisiana, where the pressure is most evident, Venture Global’s Plaquemines LNG Phases 1 and 2 are expected to add up to 2.6 Bcf/d of new export capacity upon completion. Phase 1 began production in December 2024, and Phase 2 is anticipated to commence operations by September 2025. Additionally, the CP2 terminal has received authorization to export up to 3.96 Bcf/d of LNG to non-free trade agreement countries, with operations expected to begin in the coming years. To support this increased export capacity, midstream infrastructure has been expanding; according to the EIA, approximately 8.5 Bcf/d of new takeaway capacity was added in 2024, primarily serving LNG terminals in Louisiana and Texas. While this development is encouraging, the buildout remains uneven—concentrated in the Gulf Coast, whereas regions like Appalachia continue to experience bottlenecks. To supply the growing LNG demand, projects such as TC Energy’s Gillis Access are underway. With the next wave of LNG projects nearing final investment decisions or construction, operators like Cheniere and Tellurian are proactively securing long-term gas supply contracts, fully aware that without adequate pipeline infrastructure, production commitments cannot be fulfilled

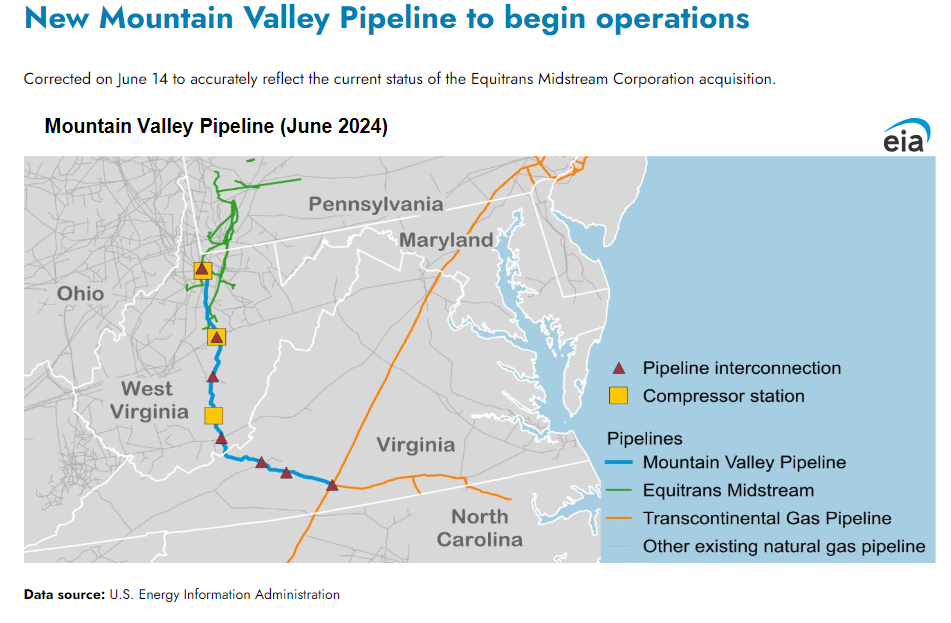

Then there’s the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP). After a decade of legal, political, and environmental delays, the project finally entered service in June 2024, following a mandate from the Fiscal Responsibility Act. The scars from that fight remain deep. MVP’s tortured permitting path became a case study in the obstacles facing U.S. infrastructure development — with years of litigation, state-level opposition, and regulatory stalls. Even after going live, MVP continues to stir conflict. In early 2025, the pipeline’s developer revived plans for its Southgate Extension, a 75-mile expansion into North Carolina, reigniting regulatory scrutiny and local resistance. Meanwhile, legal action against pipeline protesters was allowed to proceed in court, further highlighting the project’s polarizing footprint. MVP may be operational, but the permitting and public trust issues surrounding it continue — Permitting and regulatory delays now often stretch 3–5 years — and longer in contested regions — outpacing the 2-year upstream and 3–4 year LNG build timelines that dominate the market.

Appalachia is gas-rich but has historically faced takeaway constraints due to regulatory challenges. The Permian Basin has experienced flaring pressures, though recent pipeline developments aim to address offtake lags. Even the traditionally overbuilt Gulf Coast is experiencing tighter capacity utilization amid rising LNG exports. According to the EIA’s Short-Term Energy Outlook, U.S. dry natural gas production is expected to reach 104.6 Bcf/d in 2025. LNG exports are projected to rise, bolstered by new facilities like Plaquemines LNG and Corpus Christi LNG Stage 3. Regional disparities persist: Texas and Louisiana have generally been more pipeline-friendly from a permitting standpoint, attracting substantial midstream investment. In contrast, New England, parts of the Midwest, and California remain constrained, primarily due to regulatory and governance challenges.

So where does this leave us? If the U.S. wants to remain the world’s swing supplier of LNG — and meet its own electrification goals — pipeline infrastructure must become a national priority again. That means regulatory reform, permitting acceleration, and perhaps even federal preemption in key cases. Because without the ability to move gas reliably and at scale, production gains won’t translate into energy dominance. They’ll just sit in the ground.

What happens next will hinge on how fast the industry and policymakers can align. The demand story is straightforward. The production potential is proven. Now it’s up to the pipes.