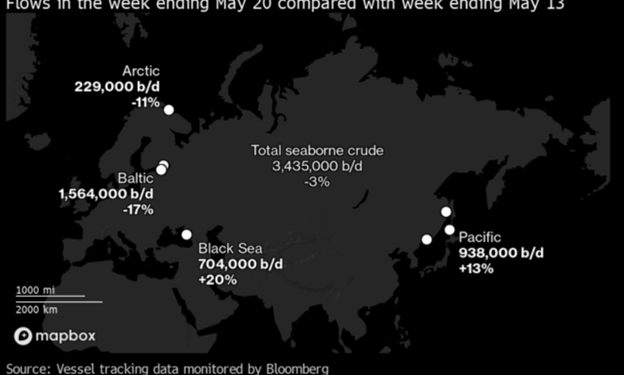

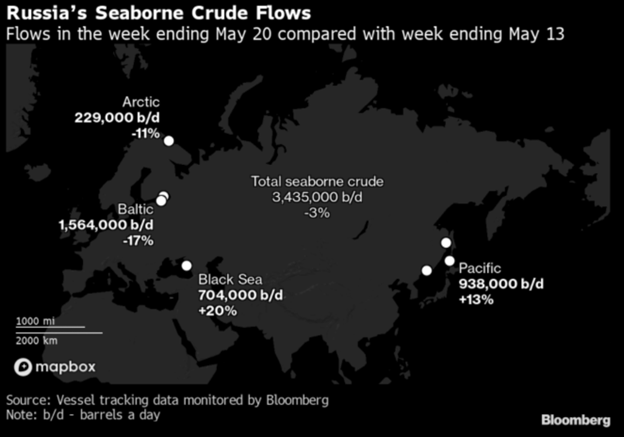

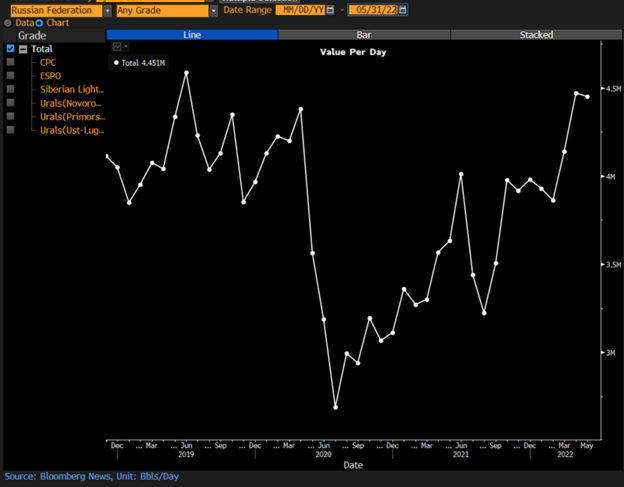

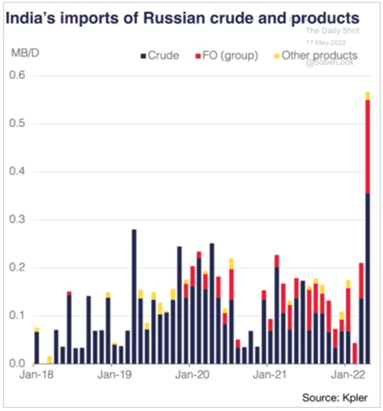

The energy markets are seeing more shifts with a record amount of Russian crude heading out to sea. “Between 74 million and 79 million barrels from the OPEC+ producer were in transit and floating storage over the past week, more than double the 27 million barrels just before the February invasion of Ukraine, according to Kpler. Asia overtook Europe as the largest buyer for the first time last month, and that gap is set to widen in May, according to the data and analytics company.” The volume of crude at sea will expand by 45 million to 60 million barrels because of the increased Russian seaborne trade with Asia if the European Union is able to agree on phasing out all imports from the nation by the end of this year, industry consultant FGE said in a note this week. The Russian shift is putting more crude on the water and increasing the miles per ton as India and China purchase more crude. It is leaving West African cargoes in floating market, which will start heading into the European and U.S. markets. As of May 26, about 57 million barrels of Urals and 7.3 million barrels of Russian Far East ESPO crude were observed to be on the water, compared with 19 million of Urals and 5.7 million of ESPO in late February, according to Kpler data.

Russia will keep shifting crude to the Pacific, which has a hard stop at about 1.3M barrels a day based on infrastructure limitations. They have slated about 4.45M barrels a day to go on the water, but have so far only been able to hit about 3.7M barrels. The limitations are on the availability of ships and total buyers that remains prohibitive to the speed to market.

India and China remain the primary destinations with more likely to follow, but the question will be at what price? We expect to see Urals, ESPO, and Sokol trading at steeper discounts as the buyers face more issues with obtaining vessels and insurance. The shortage of diesel and middle distillates in the market will keep the incentives moving forward to pull down cheaper feedstock and try to maximize margin. Refiner costs have also shifted higher as more pressure comes from natural gas and hydrogen costs, but the healthy distillate crack will keep things moving. China is boosting imports of Russian ESPO crude from the Far East, with some barrels possibly flowing into onshore storage as a Covid-19 resurgence clouds the nation’s demand outlook. Twenty of the 21 oil cargoes that have been loaded at the port of Kozmino so far this month are heading for China, according to shipping analytics company Vortexa Ltd.

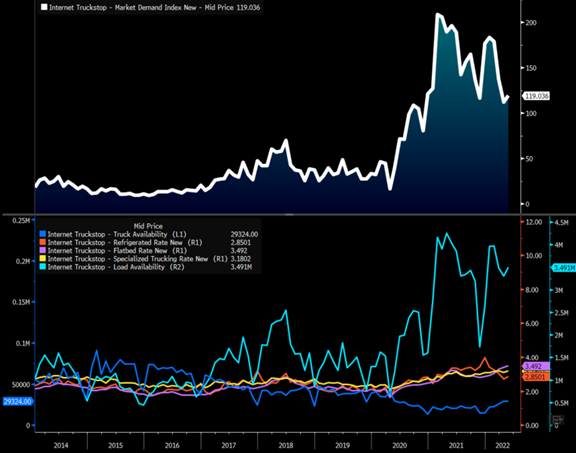

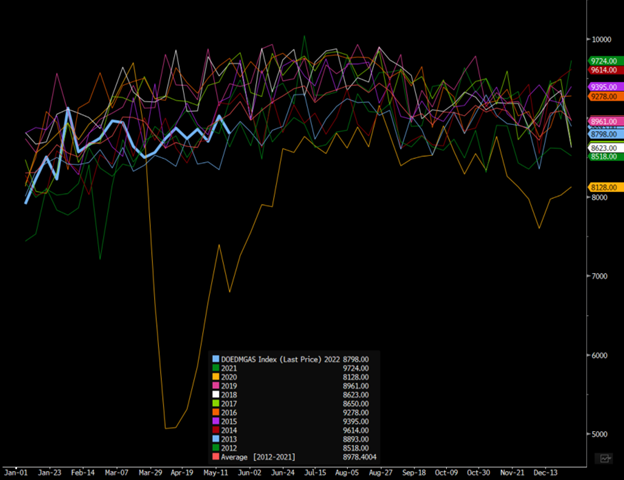

The distillate side of the equation will remain robust on a global scale, but in the U.S. will ramp up again as shipments start flowing from China. We should get a wave of backlog hitting our coast that will support trucking activity well into September, which gives way to the Christmas push. There will be enough near-term activity to hold us at around 100 but push closer to 150 in demand as the Chinese container ships start their offloading in the West.

There was a big step up in light and residual fuels in Singapore, but middle distillate still remains in a very tight market. Light distillate (gasoline) remains well supplied with residual fuel in a similar spot.

Singapore Light Distillate

There will be additional distillate coming online over the next few months out of the Middle East that will help provide some relief. China is also starting to increase exports of refined products that will also help address the underlying shortfall. Stocks of light distillates, including gasoline and naphtha, rose by 907,000 barrels or 15.9% on the week to 6.601 million barrels. The East of Suez gasoline market was seeing some downward pressure, amid expectations that Chinese exports may increase moving forward, market sources said. “I believe that gasoline cracks have narrowed significantly recently as the market is expecting a new gasoline export quota that may be as high as 3.5 million mt,” one trader said. Stocks of middle distillates, including diesel and jet fuel, rose by 592,000 barrels or 34.7% on the week to 2.298 million barrels. The gasoil market was finding headwinds from easing supply tightness pressuring the complex even as demand continues to recover across the region. Market participants are also eyeing fresh supplies coming from new refineries in the region, with Saudi Aramco’s Jazan refinery heard having begun export operations for oil products, and expectations for Kuwait’s Al-Zour refinery to start-up during the second half of the year, sources said. “Kuwait’s new refinery will be online [soon]… we heard their new refinery will be online in June or July,” a trader said.

We will see some of this additional distillate flowing into the European markets from the Middle East assets while China supplies some new flows into Asia.

The European market is in a similar spot when it comes down to gasoil (diesel) vs gasoline. European imports of refined fuels from the Middle East are headed for a 14-month high in May, driven by a multi-year surge in jet-fuel shipments that helped more than offset a drop in diesel cargo arrivals. There is way more behind it especially as the new facilities come online.

- About 43 tankers hauling 2.23m tons of clean fuels are expected to arrive in Europe from the Middle East this month, highest since October 2020

- That includes 37 tankers that have arrived with 1.85m tons and another 6 ships en route with 377k tons

- Compares with 33 tankers that discharged 2.03m tons in April, according to fixture reports, ship-tracking and Vortexa data compiled by Bloomberg

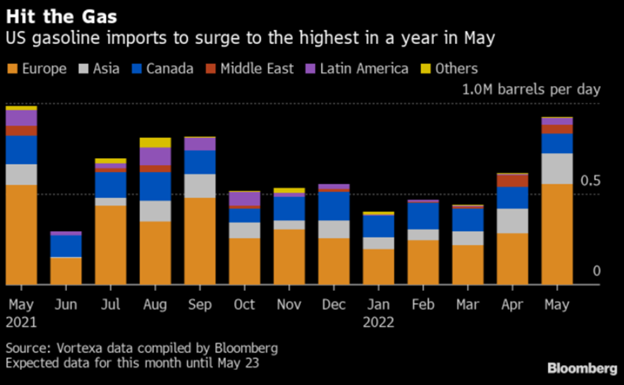

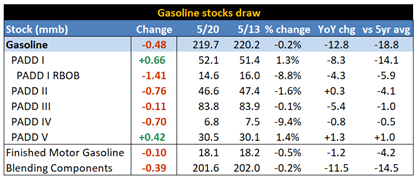

There is a significant amount of gasoline flowing from Europe into PADD1 (East Coast) to help supply some of the steep shortfalls in the region. Flows to the US East Coast from Europe will jump to about 487,000 barrels a day this month, the highest since May 2019, according to Vortexa Ltd., an energy analytics firm. The spread remains supportive of flows- and we expect more European imports over the coming few months. Storage levels had a big bounce with only 2020 having more in European storage. The same can’t be said for gasoline, which remains at near record lows and had another small draw this past week.

European Gasoline Storage

The gasoline shortage in the U.S. is mostly weighted to the East Coast- for both gasoline and diesel, which opens up the opportunity for more imports. This is why we expect the amount of gasoline heading over to stay robust. Diesel will be a way more competitive market, while there is available gasoline capacity.

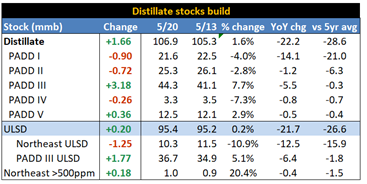

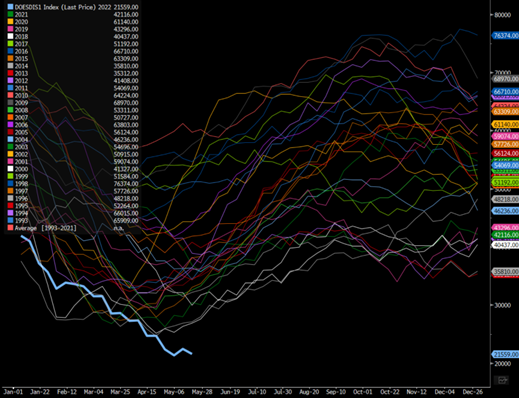

The distillate shortfalls remain on the East Coast, which is about 21M below the 5-year average.

PADD1 should be building at this point in time but is still falling putting us at record lows.

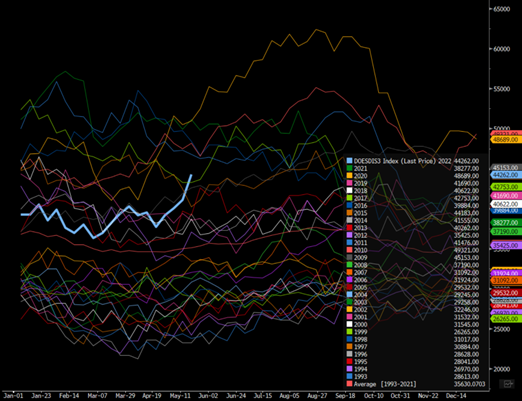

PADD 3 on the other hand has seen some big spikes in storage levels, which will keep moving higher as exports slow. More flow will be coming into the Atlantic Basin, which will cap the amount of distillate exported from the GoM.

PADD 3 Distillate Storage

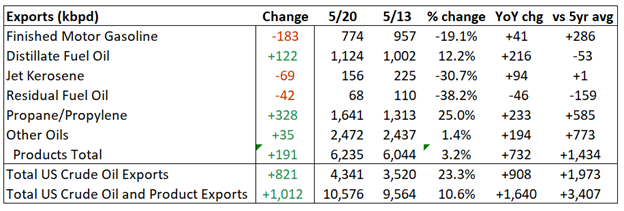

Exports will remain elevated for crude-maintaining exports at about 3.4M-3.5M with a large part going into the European markets. Europe’s crude imports from the U.S. Gulf in May are set to jump to 1.36m b/d, the highest level in at least three years- with a lot of staying power.

Exports of diesel will hold just below 5-year average with a bit more downside risk while gasoline holds above the 5year as additional product flows into Latin America- mostly Mexico.

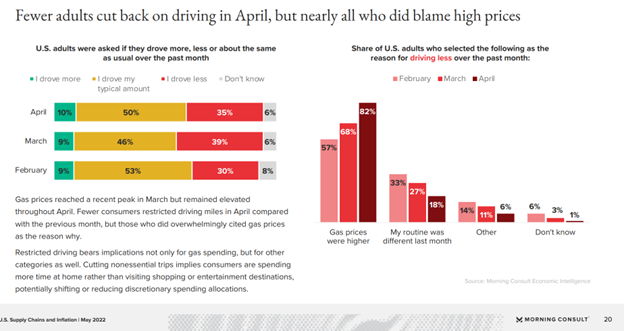

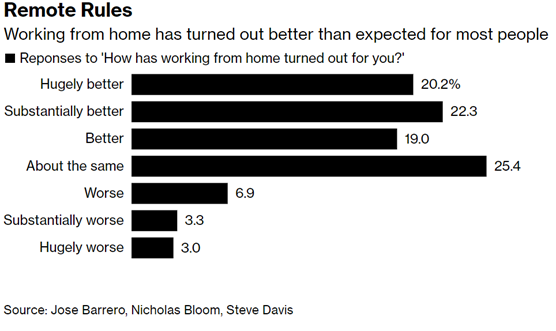

Gasoline demand in the U.S. will remain subdued as prices put pressure on driving activity and shifts in work schedules persist.

We expect to see demand have a jump for the Memorial Day Holiday but remain subdued vs other “normal” years. The pressure remains price and less people heading into the office.

The world is a living beast that has seen seismic shifts in weather patterns over the last decade with the extremes creating a growing shortfall in food and water over the last several decade. We have seen prolonged droughts in key growing areas and severe flooding creating devastation in core industrial and crop regions. The issues we are seeing today in 2022 don’t just “appear” but build on themselves with prolonged miss management and weak harvests. In year one of a soft harvest, a country can just pull down from reserves with the view that they can purchase additional capacity in the following crop year. Instead, we were hit with locust swarms, army worm outbreaks, swine and bird flu, and culminating with COVID-19 hitting supply chains hard exacerbating an already terrible food situation. China saw floods in the Yangtze River Basin that saw the feet of a Buddhist statue touched by water for the first time in 400+ years. This destroyed almost 97% of crops and livestock in the region, which is an important source of food for the country. This was exacerbated by droughts in Latin America and just general weakness throughout the world on global yields. Unfortunately, 2021 didn’t see any relief when it came to replenishing stockpiles but further drawdowns from inventory and weak global yields. The problem has been declining fish populations, weakening crop yields driven by drought and pests, and varying flus culling herds and flocks. This is a cascading event that is hitting all parts of the underlying supply chain. There are multiple examples of how this is playing out around the world, and we will touch on a few of them prior to summarizing how this is hitting every region to varying degrees.

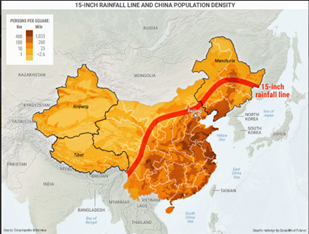

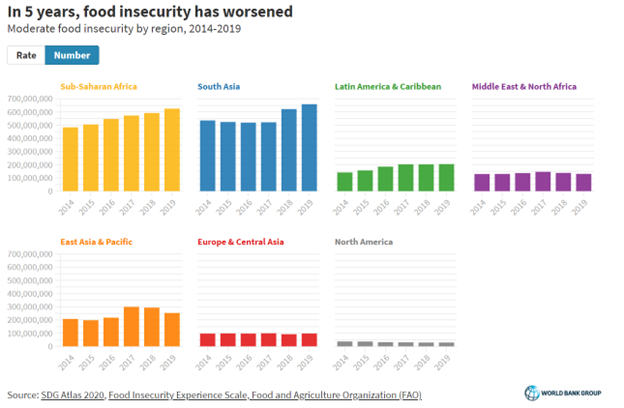

When we take a step back, there have been cracks forming all around the world going back to 2014 (as shown in a chart below), and a broad failure to address the growing problems. It also doesn’t happen in just one food category, but a cascading effect as one crop or livestock becomes short people pivot to a cheaper or more abundant alternative. So as fish availability diminishes- people rely more on chicken and pork, but those have had their own issues of swine flu and bird flu causing millions of animals to be culled. The same can be said for water as aquifers have been drained without any real concern about managing water volumes. Saudi Arabia is a great example of a country that subsidized water for decades to promote farming but are now facing a water crisis that went from “important” to a dire situation. China has been facing the same problems and has been looking to counter these problems with policy shifts both internally and externally. Within the country, there is a key limitation on the amount of food that can be grown within China. The “15-Inch Line” sets the regions that receive enough rainfall to produce crops, but most of China’s population lives on the east side of the line. China has about 21% of the world’s population but only about 12% of the world’s arable land limiting the ability to feed themselves. The CCP has prioritized fertilizer and food procurement in order to address these issues, but the sheer land and populace locations makes changing the equation to food self sufficient impossible.

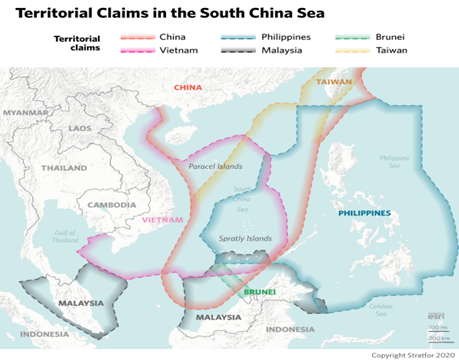

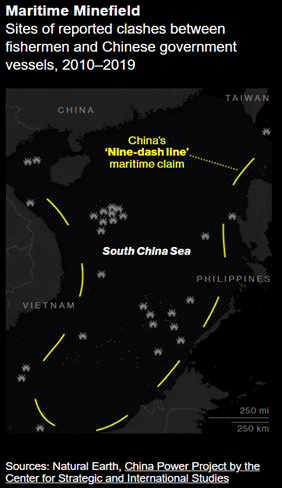

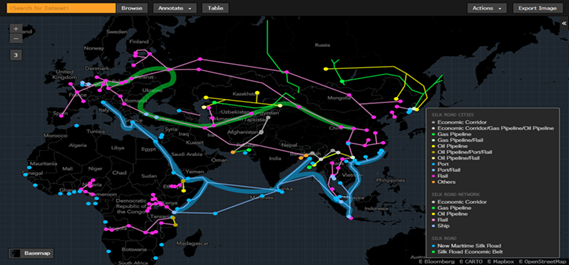

China has been addressing these shortfalls through the Belt and Road Initiative as well as their claims over the “Nine Dash Line.” China claims large parts of the South China Sea as their historical property and lay claims to these areas that just so happen to contain large fishing grounds and oil and gas assets. The U.N. unanimously rejected China’s claim across various islands and reefs that fall in neighboring countries Sovereign waters or EEZs (Exclusive Economic Zones). China has been harassing fishing vessels in the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia resulting in the sinking of vessels. The islands that China claims have also been built-up with anti-ship missiles, radar, and advanced communications to extend their reach and push navies further into international waters.

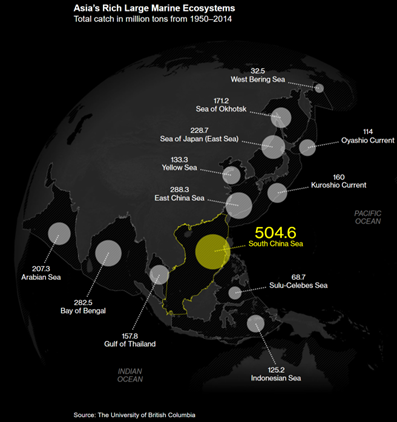

Here is a breakdown of the number of fish that is pulled from different ecosystems with the Nine-Dash Line claiming the largest.

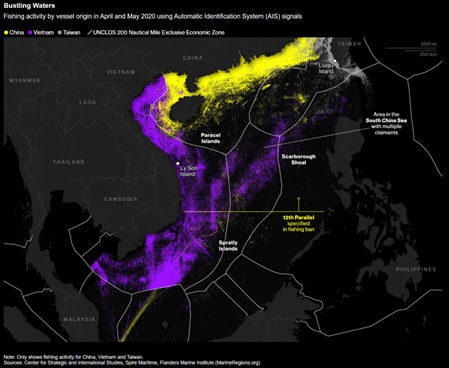

The below color-coded chart shows how Chinese vessels have been infringing into some of these key areas claimed by Vietnam under the EEZ international maritime laws.

This has resulted in clashes between governments and the sinking of vessels in some key disputed fishing areas. The U.S. maintains freedom of navigation trips through these disputed areas to support trade line and international waters. This has led to more friction between the U.S. and China, but the growing shortfall of food within China means they aren’t going to back down anytime soon.

China has expanded their influence around the world through the Belt and Road Initiative that has opened up ports, factories, mines, and other infrastructure for Chinese businesses. They have also used their position in Africa to increase commercial fishing, but due to overfishing and disregard to international standards have had their fishing licenses revoked. The problem is that none of the countries have the naval capacity to enforce the revocation or they are worried about scaring Chinese investment away from their nations. As fish populations have diminished, China has looked to expand their footprint in key producing areas.

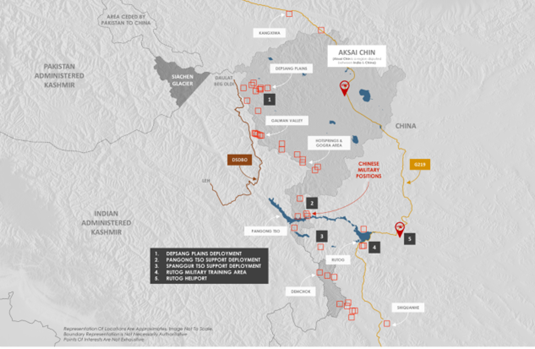

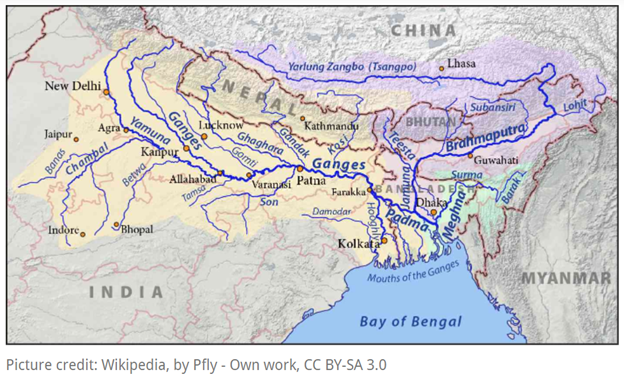

China has also been building dams to control water flows throughout their country in an attempt to prevent flooding and irrigation for farmers. This has led to political conflicts with surrounding nations, such as India and Vietnam. India and China came to blows in Ladakh, which is a key crossroads for the Indus River (Zanskar River- locally). Pakistan, India, and China have contested areas throughout the region that is a key bloodline for water that flows further south. The Indus Water Treaty has existed since 1960 and has last throughout many skirmishes and disagreements, but the terms of the agreement are getting pushed to the limits and could result in a broader conflict- especially as droughts expand in the region.

“During the border crisis in 2020, China established improvised positions at key locations along the edges of its own territorial claim in the region. Chinese forces established tent camps in the Galwan Valley, occupied critical patrol points, sent forces to camp atop mountain ranges along high altitude lakes and set up new bases in open plains. Negotiations during the crisis itself led China to abandon a small minority of these improvised frontline positions, but over the next two years, the vast majority of them developed into permanent all-weather military encampments. The strength that China has rapidly developed along these borders will severely constrain India’s ability to ever recover access to the Aksai Chin region. Despite the public appearance of the crisis being settled in a Chinese withdrawal, this withdrawal has remained negligible compared to the scale of the territory that China has militarized. As such, China has achieved a form of territorial expansion by bringing Aksai Chin from a disputed status to a de facto militarily occupied status. India has, of course, not been entirely passive throughout the course of the crisis and the two years that have followed. Initially, its stern response to Chinese expansions into the Galwan Valley quite literally pushed back the Chinese efforts to establish new positions, but its risk-averse approach did eventually allow the Chinese military to dig in at Aksai Chin.”[1]

China has dug in laying claim to these key areas, while issues remain pervasive around Kashmir between India and Pakistan. The Indus Valley is a pivotal crossing point for these three nations- especially as China has expanded their involvement in the region with the Pakistan-China Economic Corridor. This has increased their involvement and the important of water to their projects. China announced the potential for a 60 gigawatt facility on the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo river. The Brahmaputra is called the Yarlung Tsangpo or the Yarlung Zangbo in Tibet, where it originates. India reacted almost immediately. A top official in the Jal Shakti ministry told journalists of India’s plans to build a 10-gigawatt project on the Siang, the main tributary of the Brahmaputra that connects it to the Yarlung Tsangpo, to “offset the impact of the hydropower project by China”. The “Water Wars” exist all around the world as the commodity is becoming a bigger problem.

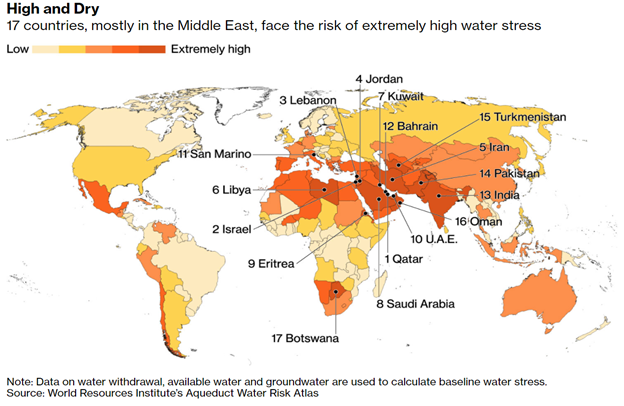

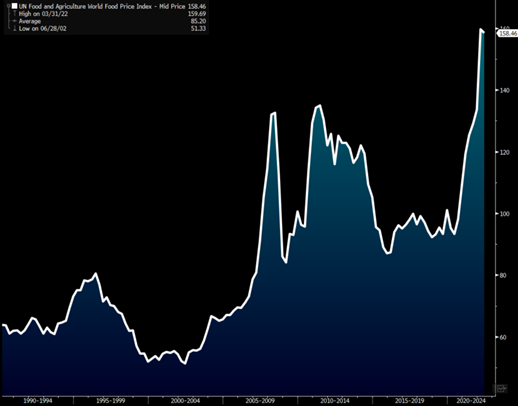

The issues have been expanding in key areas with Central Asia, Latin America, and Africa key area that are seeing an increase short fall. For example, in 2019, Iran was ranked 5th in the world for water scarcity, and based on the current protests and water levels, it has only been exacerbated since then. The water shortage creates multiple problems: from safe drinking to crop yields to maintaining animal herds. To fill the void of crop shortages, the country must rely more on the import market, which opens them up to global pricing pressures. The U.S. sanctions only complicate Iran’s ability to access the international markets for driving inflation to the stratosphere. The people of Iran have faced economic pressure and rampant inflation before, but as water and food (basic necessities) scarcity grows, it will drive people to action. We have seen it happen around the world—especially in Emerging Markets—where COVID19 has created significant stress on supply chains and underlying commodity prices. The Arab Spring took place during a time of elevated political and social pressure, but it was also a time of droughts, heatwaves, and high food prices, helping to fuel the unrest. In today’s market, food prices have blown through 2011 levels with a water situation that has only gotten worse since the Arab Spring. All of these factors leave nations facing a powder keg of political uncertainty. Without addressing the underlying problems, civil unrest, economic stress, and instability are just getting started.

Another example is the Ethiopian-Egyptian Water war regarding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. The dam has created rising tensions between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia on the Blue Nile. The highlands in Ethiopia supply more than 85% of the water that flows down the river. There is a concern that the downstream markets will be cut off from vital water flows that are needed for the local population drinking and irrigation.

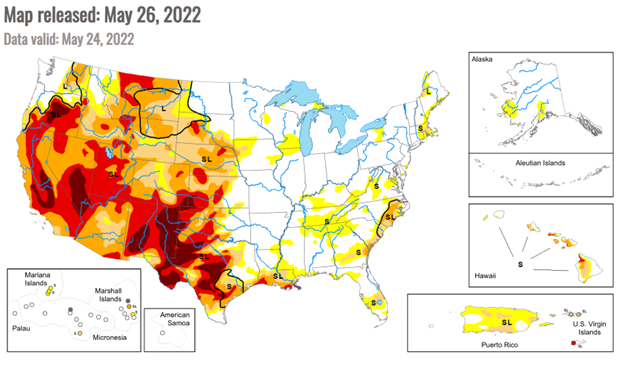

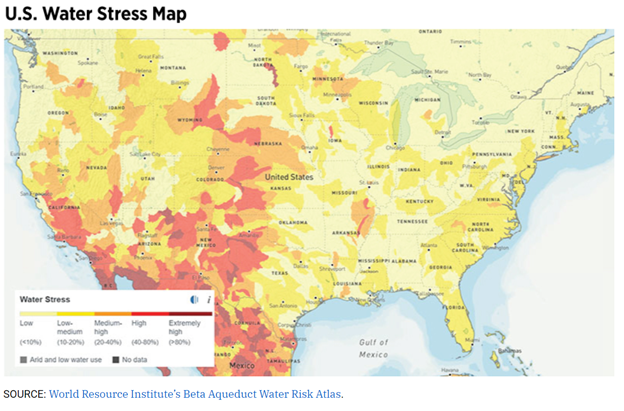

The U.S. doesn’t escape these issues as droughts have become more prolific and extreme in the Midwest, south, and west coast. The extreme shifts have created water scarcity in population growth regions and significantly diminished yield in many of the core growing regions. This has played out in Brazil as well that has seen a significant drop in rainfall impeding their yield and growing season.

The shortages shown above to the water stress that has yet to be truly alleviated.

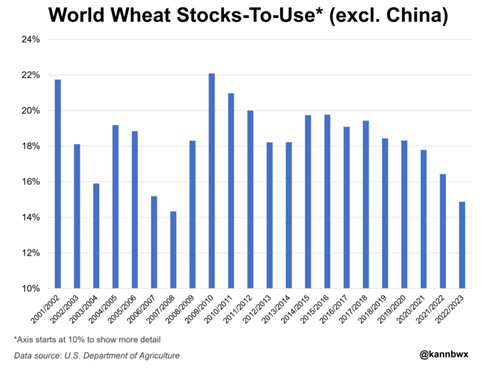

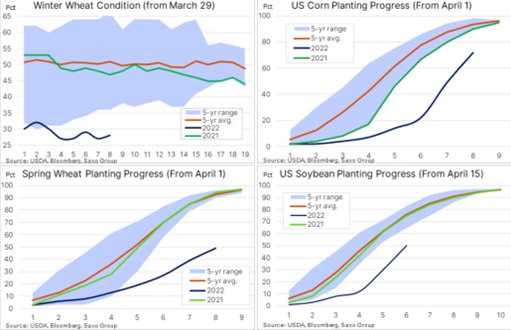

India has recently banned exports of wheat (3% of the global market) and put a cap on sugar exports at 9M with the ability to sell another 1M with government approval- but capped at 10M. USDA’s attaché has cut 11 million ton (404 million bushels) off of India‘s wheat harvest after an extreme heat wave. The harvest is now seen at 99 mmt vs 110 mmt last month. They see 22/23 exports at 6 mmt at best versus 10 mmt projected previously (and that’s with the ban). The food situation is deteriorating and has been even before the Russian-Ukraine war that only exacerbated a terrible situation. World wheat stocks-to-use has been falling since 2019, and only gotten worse as the weather patterns have shifted cutting yield. Many of these issues were pervasive BEFORE Russia invaded Ukraine impacting exports from those two countries. U.S. spring wheat planting is advancing at the slowest pace in more than 20 years and was only 49% complete as of Sunday with the average for the date normally 83%. Wheat prices could remain elevated into 2023 if this forecast holds true. USDA pegs world wheat stocks-to-use (excluding China) at 14.9% in 2022/23, the 4th lowest ever and the lowest since 2007/08 (14.3%; all-time low) which is down from 16.4% in 2021/22- showing the steady degradation of the situation.

The issues in the U.S. are hitting all levels of planting as we look at progress across our key crops.

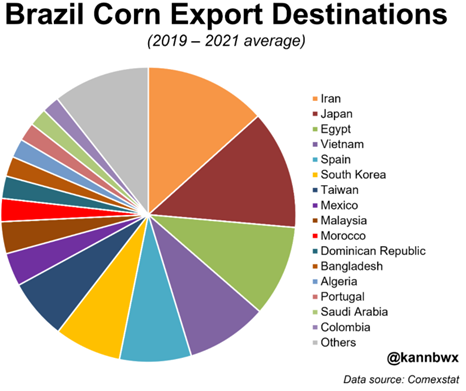

The fear in the market is causing countries to horde more food, start buying next year’s crop and fertilizer, and abandon restrictions on some imported products. For examp,e China has signed an agreement with Brazil to allow imports of their corn that was previously subject to phytosanitary restrictions. This is going to pull more product away from other markets- such as Iran, Egypt, and Vietnam (to name a few) that won’t be able to compete against the prices China is willing to pay.

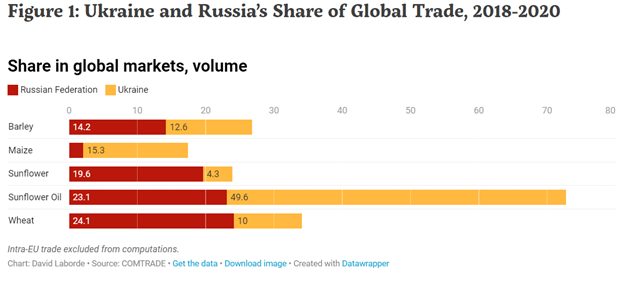

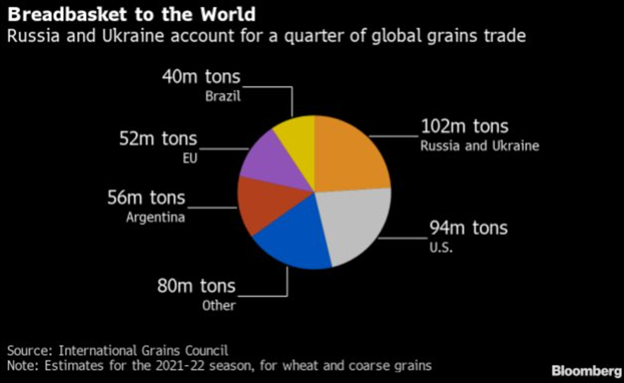

The Russia-Ukraine war takes additional capacity out of the market with both countries a huge component of the global markets. “Russian President Vladimir Putin said he’s willing to facilitate grain and fertilizer exports as global concern mounts about food shortages and rising prices — but only if sanctions on his country are lifted.” Russia is trying to play food diplomacy, but there were already issues with their harvest BEFORE they invaded Ukraine. The estimates were already being cut and export limitations in place as yield was already a problem. Ukraine on the other hand had their ports shuttered and farmers called to war instead of planting their land.

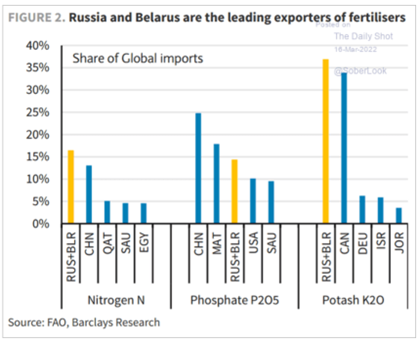

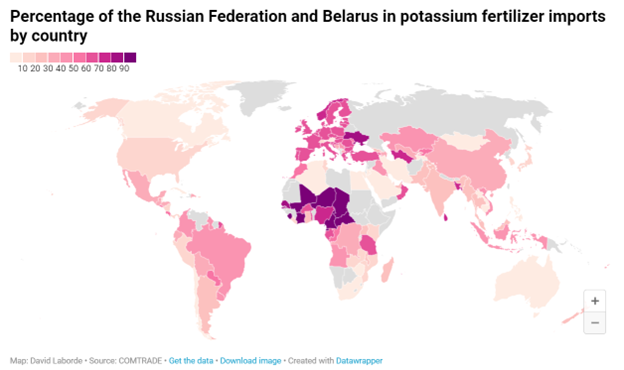

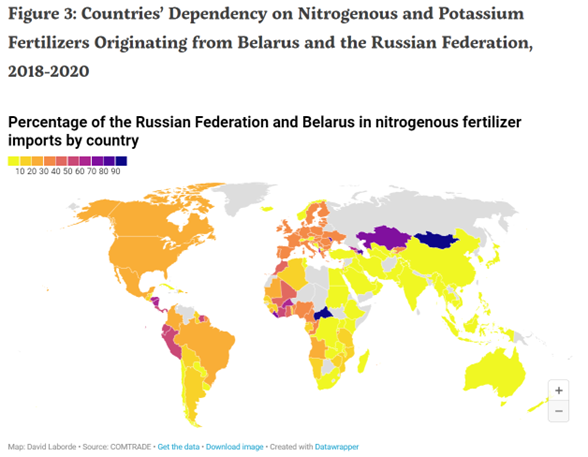

The impacts also go beyond crops and impact fertilizer shipments around the world that originate in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. Russia and Belarus are a big part of the global nutrient that are required to maintain the yield we have become accustom too. A large part of this volume has been removed due to sanctions and logistical bottlenecks that have cut the availability of fertilizers. This has caused price spikes globally and shortages that have expanded into 2023. The shortages are stressing countries with inflation already spiking in Africa and Central Asia.

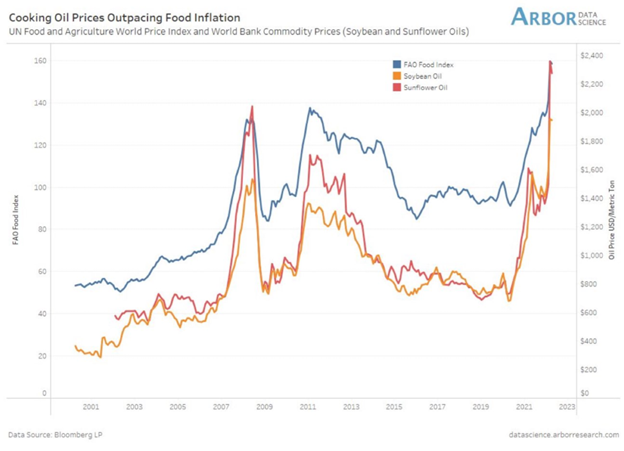

Constraints on food supply are not abating, and as Ukraine exports more than half of world’s sunflower oil on top of South America’s recent drought has spelled uncertainty for soybean oil supply, adding pressure to global food crisis.

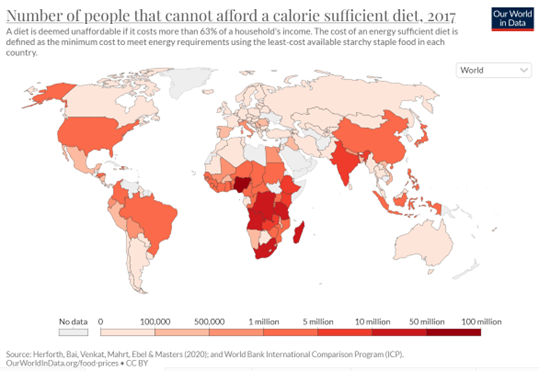

As prices rise, there is a growing amount of people that will not be able to afford enough calories per day. “A person can eat an energy sufficient diet on less than $1 a day. The global average price for this diet across all countries in the study was $ 0.84 per day.[2]” This figure was from 2021, which has only gotten worse when we look at 2022 prices and what the expectations are going forward.

Food insecurity was already GROWING prior to COVID-19, and now with shifting weather patterns and war- the issues are being exacerbated. In 2019, 80% of global incomes in struggling areas were spent on food, which has only pivoted higher. “Unsurprisingly, a diverse, healthy diet is much more expensive than a calorie-sufficient one. The researchers found that the average cost across the world was $3.69 per day. That’s more than four times higher.7 When we put these prices in the context of affordability – again defining this as spending 63% of our income on food – we find that three billion people cannot afford a healthy diet. In many of the world’s poorest countries – particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa – it’s unaffordable (or not producible) for most of the population. This is shown in the map which gives these figures as a percentage of the total population. In many countries, a healthy diet is out-of-reach for more than 90%.” When you look at the chart, even in the U.S. we have an inherent problem of enabling everyone to receive enough calories per day.

Globally, the number of poor is broken out into several categories based on the “depth” measured by USD payments per day—with the lowest being $1.90 and highest just below $6. The World Bank has seen the global poverty figures declining steadily over the last several years. Since 2019, the trajectory started to shift and COVID19 sent us on a completely different path higher due to lack of earnings potential. Now, with the U.S. 10-Year Treasury Bill above 3% and climbing, the cost of borrowing has risen, limiting the underlying stimulus a government can provide through subsidies and economic incentives. Countries around the world issued a record amount of new debt to stimulate their economies that increased their underlying leverage. This huge spike in debt mixed with several years of easy monetary policy has opened the flood gates for inflation. We are already seeing fuel costs rise globally with little ability for governments to protect or limit the rise. As our rates go up (10-year is typically the global “risk free” benchmark), countries are finding it harder (and more expensive) to access the markets. This is why I believe we will see the number of people not available to afford food rise exponentially —especially in Africa and Asia. In the United States and Europe, the extremes of destitution are vastly different, but that is not to say that people aren’t reaching the same levels of despair and “hopelessness” as other people in poverty around the world.

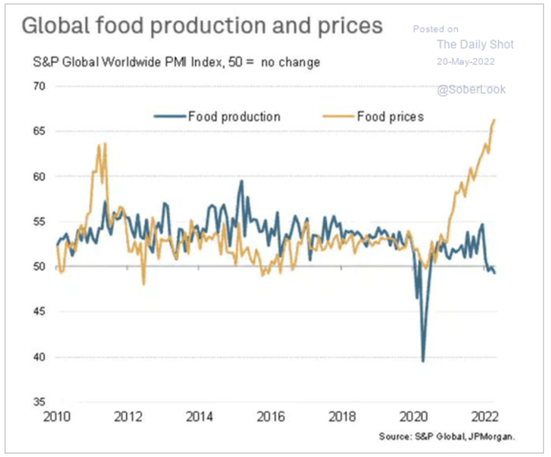

As global food production falls- it will support a large push higher in food prices that have blown through the levels we saw in 2011 that ushered in the “Arab Spring” or “Peasant Uprising.” The charts below help show just how high prices have gone and with yields falling to this degree- prices have a lot of staying power in this area. When gasoline/diesel prices spike, you have the option to “not drive” but who can stop eating? The global population has continued to grow even as yields have fallen across all food forms- plant and animal. This is causing a broader issue as we project forward.

Historically, social unrest and uprisings have often followed widespread illness, and this does not bode well for a global economy that was already not in a good place in 2019. Those countries with the least economic support (Emerging Markets and Low-Income Countries) face the greatest likelihood of problems, as stimulus is harder to achieve on a monetary and fiscal level. Time. We may be returning to some normalcy, but as people go longer without food, work, or other basic needs, anger increases, and the chance of unrest goes up exponentially. There is always a lag in the “anger” or expression of frustration as people are unlikely to protest/riot at the peak of a pandemic (or in this case, COVID19). Typically, poor nations are exposed to more disease and epidemic spreads, which keeps their economic development running in place and exhausting government support quickly. We are now facing a rise in food shortages and cost, and when people can’t feed their families, desperate actions and measures are taken. Life requires food and water to survive and without we perish quickly. As a father, I can attest that I will do whatever it takes to protect my family, and what will a desperate father watching their family starve or die of thirst do? What actions will they take to protect the ones they love? Maslow’s hierarchy has stood the test of time because without water and food to support the base of the pyramid- everything else comes tumbling down, and right now that foundations looks unstable.

[1] https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/china-india-border-crisis-has-quietly-resulted-in-victory-for-beijing [2] https://ourworldindata.org/diet-affordability