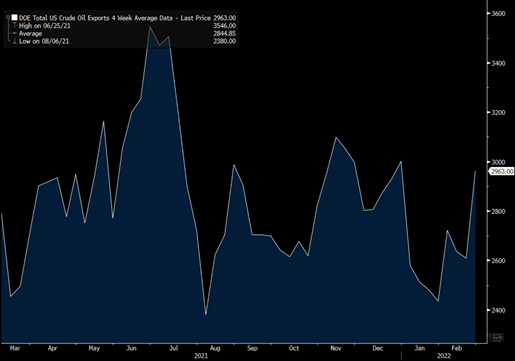

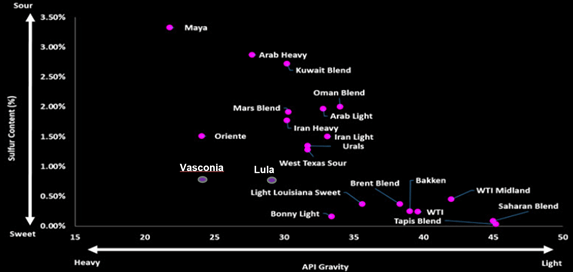

The U.S. completions market should remain healthy, but the ability of the U.S. market to see a huge “surge” in production is near impossible. We are sitting in a market that has broad shortfalls and supply chain bottlenecks across proppant, pipe, casing, labor, and just available horsepower. Even if an E&P wanted to increase their drilling program by 25%, there are significant supply chain shortfalls to achieve that increase. There are also many limitations that will spring from Russia as well ranging from met coal to nickel to diesel. The U.S. has been a big importer of Russian diesel into PADD1, and we have now seen that move to zero. Another big hinderance is the way our refiners are constructed because on average they run 33 API crude. U.S. shale averages 42-48 and that is after it has run through a splitter, which means we will still need to rely on the international market for volume. We have already seen a pick-up of purchases from West Africa and the Middle East in order to bring new volume. The U.S. will also look to max out purchases from Canada wherever possible to bring the heavy crude down to PADD3- boy it would be nice to have a pipeline for that right now… 😊! But, the additional U.S. volumes have seen a big step up in demand international- specifically into Europe. This will support exports in the U.S. and keep us at around 3M barrels per day. So even if the U.S. refiner isn’t running it- there is enough demand abroad to keep our energy industry trying to hit on all cylinders.

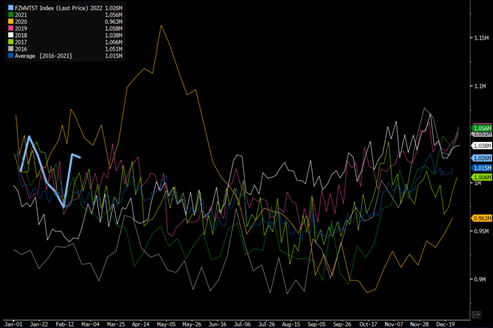

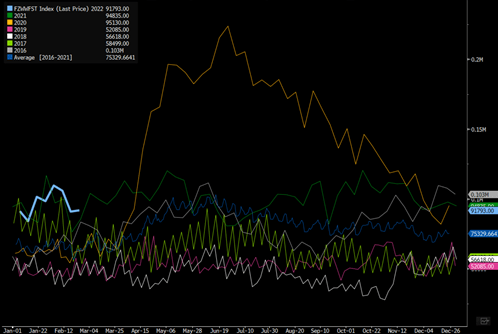

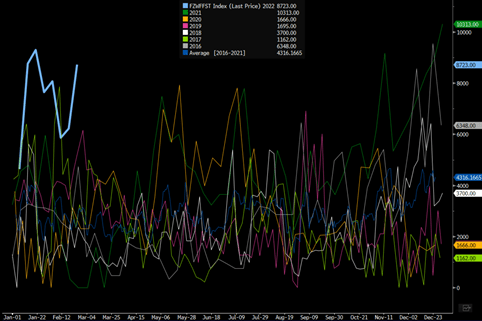

There has been a lot of spot work available that has pushed the frac spread count higher in the near term, but we will see some of that roll off this week and next. We will continue to see a lot of activity in the Anadarko, Haynesville, and Permian with a lot of the growth weighted to the Anadarko in the near term. The liquids market remains white hot- especially with the steep drop off in storage and steady demand in the market. Total completion activity ran to 290, but we should see it pullback a bit (by 5-7) over the next 2 weeks or so. As we head into end of March/April, there will be a steady march right back to 300, but the move past 300 is going to be difficult as equipment shortfalls remain throughout the U.S. When we look at broad activity, the Permian is now running at peak levels, but we still have room to see an increase in the Anadarko. We will likely move closer to 20 spreads in the Anadarko over the next few weeks as the Permian holds firm over 150.

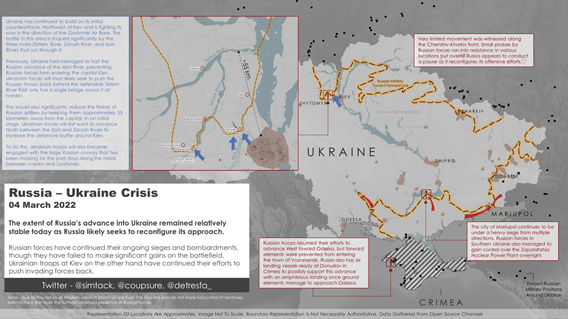

In the North, the Russian military momentum has ground to a halt due to broad logistical issues ranging from diesel shortages to equipment breaking down. We have seen countless examples of mechanical equipment that wasn’t properly maintained breaking down. The other BIG issue that we called out in December is the “Mud Season” or Rasputitsa. These leaves equipment beholden to the roads and elevated ground, which limits their maneuverability. This has allowed for broad counter attacks that the Ukrainians are using to strike blows across the Northwest of Kiev in the direction of the Gostomel Air Base. The Ukrainian military is using the three rivers very effectively to hinder the Russian movements while striking on the rear guard/supply lines. By stopping them here, they can keep Kiev outside of Russian artillery range.

Things are not going as well in the south when you look at the Russian troop advancements towards Odessa and surrounding Mariupol. So far- the Ukraine military has been able to make a stand at Voznesensk that has slowed the progress towards Odessa. Russia has been unable to full close off the Black Sea to Ukraine, but it is just a matter of time before we see more advances across this region. There are rumors/ satellite imagery that shows landing vessels preparing in Crimea that will likely be used in concert with a ground attack on Odessa. Mariupol remains under siege as they try to hold off the advances from Russia from all sides. There has also been fighting around the largest nuclear power plant in Zaporizhzhia.

In the West- there has also been limited movement along the Chernihiv-Kharkiv front, with the biggest issue also being logistical shortfalls and Russia unable to take air superiority. The Ukrainian airforce remains intact to a degree, and has been able to strike key supply lines and keep Russian fighter jets/bombers limited to night raids. Due to the lack of sophisticated bombs, the effectiveness of the night raids has been muted. Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea have stopped shipping electronics and components to Russia, which is a huge blow to not only their tech sector but also their military capacity. There have been rumors that Russia was running low on missile components, and if that is true- losing Taiwan shipments will halt essentially all military manufacturing at that level. Taiwan produces a large amount of the technology components for sophisticated missiles.

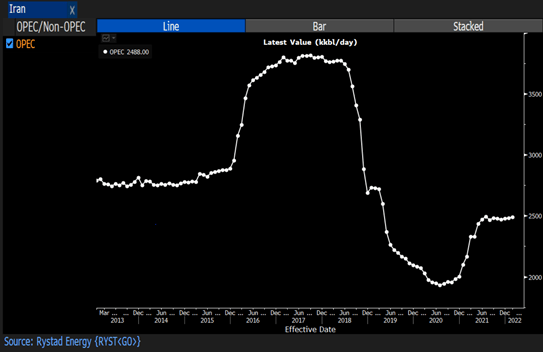

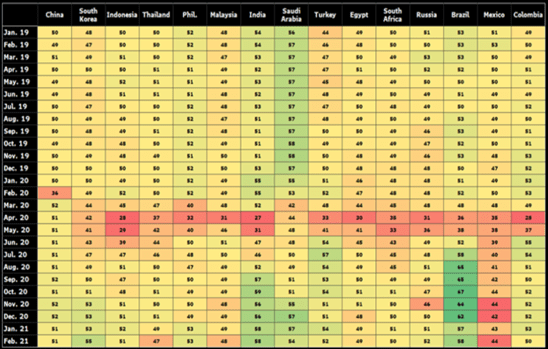

The Russian-Ukraine situation remains front and center as it hits every commodity in the world as Russia pushes further into Ukraine. Urals have gone “no-bid” as refiners and banks avoid any Russian grades. Even though there are “officially” no sanctions, banks/companies don’t want to be caught with a product that may fall under restrictions. This has led to a swift decline in demand for Russian crude, and it is unlikely to find a home in the very near term. There are varying grades that can replace urals, but the closest is “Iran Light.” Iran is still under sanctions and faces limitations on where their crude can be sold. Iran has been able to sell crude in China as “Malaysian”, and they have quietly increased exports into India. The U.S. has allowed these flows to help them (especially India) manage inflation, but we are inching closer to a deal that would unlock storage volume that could flow into Europe. The proof of the rising imports of Iran into China can be seen in Angola/Congo. We have been discussing for months (probably over a year at this point) that China hasn’t been buying their normal volumes from West Africa. They opted for the discounted barrels coming out of Iran instead of the fully priced WAF cargoes. We are now starting to see more volumes clearing from WAF as Europe scrambles to buy more volume, which has pushed Nigeria/Angola to add cargoes to April’s schedule. We have also been covering the weak Chinese economy for a long time now, and it is also driving a lot of the drop in demand. China is also pushing further on avoiding Russia/Belarus with the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank pausing all activities in the country. China is in a tough spot because they need food- grains as well as exports to help support their economy. All of this keeps them beholden to the West, and they will have to walk a tight line when dealing with Russia relations. They will still buy NG, LNG, oil, and other commodities from Russia, but they will stop/limit all investments in the country.

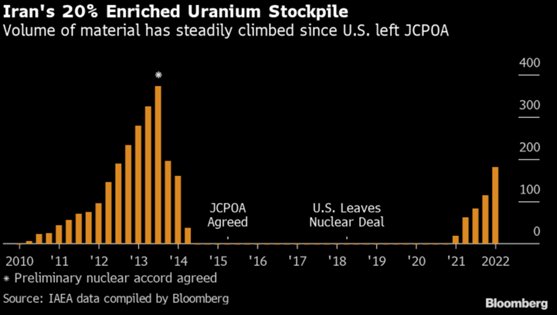

A bigger Iranian production boost would take some more time, but we will see it accelerated with crude quickly moving into Asia and Europe. We could see a quick spike of about 1M barrels a day, but Iran is now negotiating much harder because they have WAY more bargaining power now. “Iran sharply raised stocks of highly-enriched uranium and continued to stonewall inspectors, the global atomic watchdog said, as its chief prepares to fly to Tehran for talks that might help revive the 2015 pact that had reined in the country’s nuclear program.”

Iranian stockpiles have been growing again, and Iran is seeking much broader securities on how long the agreement can exist. They want to ensure another government won’t be able to rip up the deal, and they refuse to stop ballistic missile testing. “The original accord gave IAEA monitors unprecedented supervision over Iranian nuclear facilities, which they partially lost after the Trump administration unilaterally withdrew from the agreement to impose sweeping U.S. sanctions. Other issues to have bedeviled talks in the Austrian capital include an Iranian insistence that the Biden administration guarantee future U.S. governments won’t again leave the pact, and how to roll back Tehran’s nuclear advancements. The IAEA has been probing the source of uranium particles detected at several undeclared locations in Iran. European and U.S. diplomats have previously threatened to censure Tehran over its lack of cooperation with the watchdog, which convenes its next board meeting on March 7.”

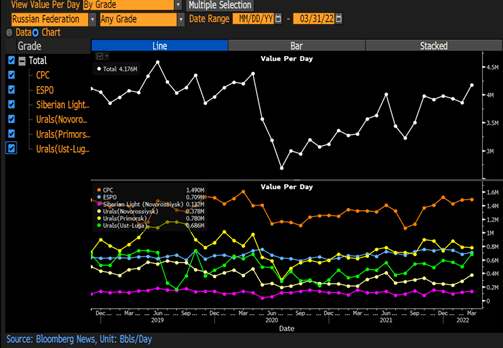

We will likely see China continue to purchase ESPO and SOKOL, but it will be difficult to purchase anything from the Baltic region as insurance and freight rates surge. We have Baltic day rates at $240k a day and insurance essentially impossible to obtain making FOB (Free On Board) impossible to purchase. This will leave a significant amount of Urals in the market without a home. India purchased about 6M, but it will be near impossible to purchase anymore- unless the RBI is willing to put up money for insurance. To be clear- the RBI and PBoC have done that for Iran.

There is about 1.844M barrels a day of Urals leaving 3 different ports that will be stuck at the coast. Russia is short on storage so as tanks fill up quickly- they will be forced to shut-in production. The 60M barrel release from the SPR was essentially meant to replace those barrels, and whatever may be lost from Russia.

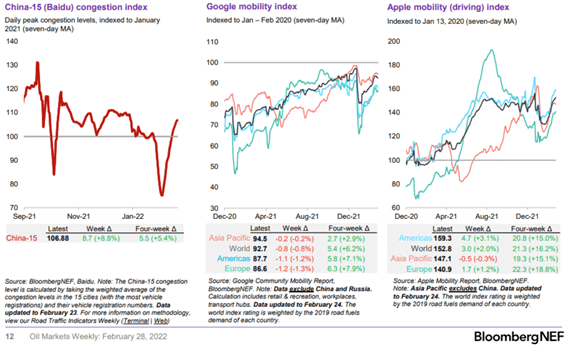

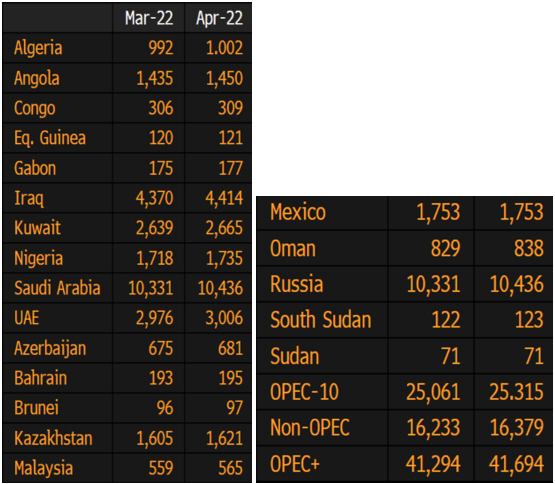

Following the OPEC+ meeting, Russia can produce 10.436M barrels a day with some of it still able to find a home. It will be limited, and we are already seeing broad discounts on other blends- such as CPC that is now $8 below dated brent and falling. Kazakhstan still sells a significant amount of crude through the CPC blend, so it isn’t 100% Russian- which is why it is a differentiating factor for that blend moving into the market. ESPO and Siberian Light will keep being purchased by China, but Chinese traders already purchased enough crude to meet Q1 quotas. China has started the process of exporting more diesel and gasoline into the market, and we should see additional flows over the next few weeks. Chinese demand for product (gasoline-diesel) has been weak and will remain well off seasonal norms. There was finally a jump in driving, but it still remains measured, which will put more refined product on the water. India also had a disappointing diesel demand number while gasoline demand spiked again softening the blow on the read thru from diesel that indicates economic activity.

- Diesel sales by the three biggest retailers were 5.77m tons, 21.4% more than the first 28 days of Jan., officials said, citing initial data

- Still, sales of the country’s most-used fuel were -0.9% y/y and -4.8% vs Feb. 2020, before the pandemic hit India

- Gasoline sales +23.8% m/m to 2.29m tons, +3.3% y/y and +7.1% vs Feb. 2020

- India’s daily new infections dropped below 7,000 on Feb. 28 from 167,059 on Feb. 1, leading to a further easing of restrictions and reopening of schools and colleges

Globally, mobility has yet to reach “normal” levels with U.S. demand also falling short. We expect to see sluggish demand as inflation ramps further, and the consumer continues to come under more pressure.

The OPEC+ meeting delivered an expected increase of 400k barrels a day, but next month will be more important as the deal expires April 2022. This will be an interesting meeting to see if the new group can stay together as we head into a very precarious economic backdrop with WTI over $100 and Brent over $110. Exports from the Middle East were increasing through February as Dated Brent surged above Oman/Dubai. Concerns over Urals started well before Russia invaded, and we saw refiners turning to the Middle East for additional cargoes. It will be important to see how much crude is slated for exports out of the ME and WAF. We already have Angola/Nigeria adding cargoes and companies are now requesting more volume from Iraq. The country took down some fields for work, but it is likely they will be back online quickly in order to capture the spike in pricing and rising demand for their grades. “Iraq stopped oil production from two southern fields with a combined capacity of almost half a million barrels a day. The operators of Nasiriya and West Qurna-2 have said nearby fields will be able to produce more to compensate for the temporary losses. Work at Nasiriya, capable of supplying as much as 80,000 barrels a day, was halted on Saturday because of protests that prevented staff from reaching the site, according to a statement from Thiqar Oil Co. That followed the closure of the huge West Qurna-2 field on Feb. 21 for maintenance. The field, which can pump 400,000 barrels a day, is scheduled to resume normal operations on March 14, though the companies that run it are trying to restart output sooner. State-owned Basra Oil Co. said the work will enable production from West Qurna-2 to be increased to 450,000 barrels a day. Russia’s Lukoil PJSC has a stake in the field.” OPEC will have some flexibility to increase production, and it will be a test on their spare capacity. Exports will be the best way to view the near term flows, which I expect to see a steady increase of out of the ME and WAF.

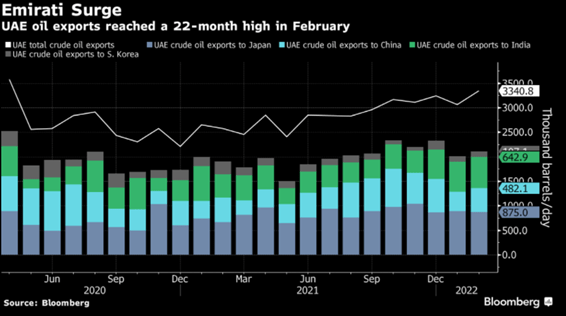

The UAE is just one example of a country that saw their exports spike, and we expect to see more flowing from the region. Shipments to India surged to a 13 month high while China flows also gained, but I expect to see more flowing and they will take out the 2020 highs. The UAE has expanded their production capacity, and I expect them to capitalize on it- especially as the current OPEC+ agreement expires.

The Brent-Dubai spread is sitting at $13.50, which is going to keep European cargoes flowing local while ME crude sees their demand spike. West Africa will respond as well, but they price off of Dated Brent- so even as their demand increases- we could see spreads dip a bit to remain competitive. It is less about “poor” demand and more about maintaining flows. UNIPEC is currently offereing 5 cargoes of Angolan crude, which they are probably trying to flip given the spike. But- it also shows that they aren’t concerned (yet at least) of crude availability and are willing to part with cargoes. It will be important to see how China is buying, but if they show up in a meaningful way- things could tighten quickly.

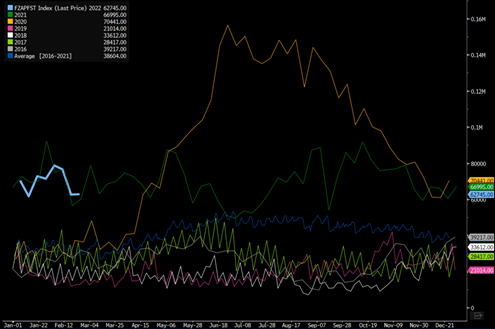

They currently have a record amount of supertankers heading into their region with a record amount of crude in floating storage, but if they see demand starting to increase we could see another spike in crude sailing to China.

SUPERTANKERS SIGNALING CHINA

ASIAN FLOATING STORAGE

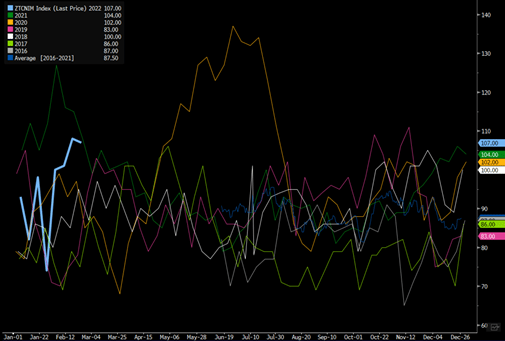

We are starting to see teapots and SOE refiners increase run rates, but the ramp has been fairly measured against historics. China will likely increase runs, and push out more exports to capture the big spike in refined products- specficially Diesel.

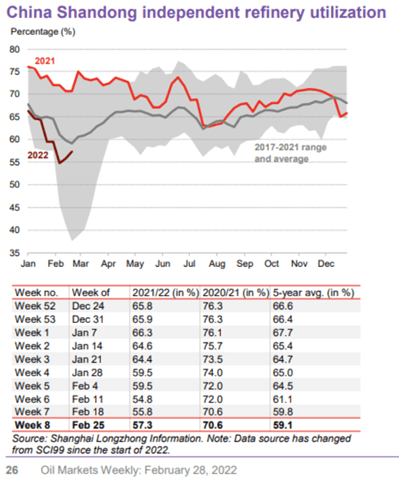

There remains a large amount of crude on the water, but we will see more in storage shift to transit as Europe and Asia start absorbing new capacity. We currently sit right at all time records with only 2020 being a similar year- I think we will be surprised at how much crude is being put out on the water from the ME.

CRUDE OIL ON THE WATER

I expect to see a big pick up on crude in transit again as more cargoes shift into motion coming from West Africa. There is enough capacity at this point in WAF and ME to push crude oil in tranit above the 2020 highs.

CRUDE OIL IN TRANSIT

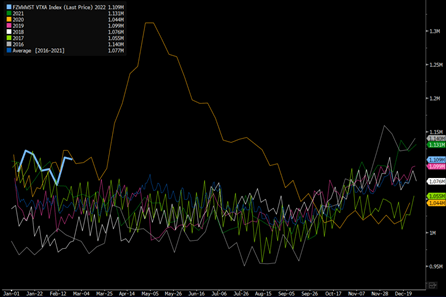

There should be a near term dip floating storage as more cargoes shift into motion. This will be a big tell on how tight the physical market is getting as these dry up. The question will be how quickly does WAF and ME increases exports to capture elevated pricing and replacing the loss of Russian crude.

GLOBAL CRUDE OIL FLOATING STORAGE

There is still spare capacity in West Africa, but we are seeing more sail towards Europe at this point.

WEST AFRICA CRUDE OIL FLOATING STORAGE

Shell is now the first country to purechase Urals at a discount of $28.50 to dated brent- this will be intereting to see how the general public takes it.

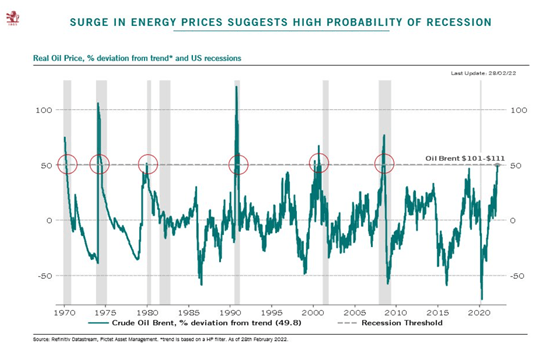

The global economy remains under severe stress as all commodities continue to shift higher. The below chart does a good job of showing what happens when Brent heads above $101- it is usally quickly followed by a recession. The cost of doing business shifts higher across all aspects of life, and this time we have inflation hitting all parts of the economy… nothing is spared.

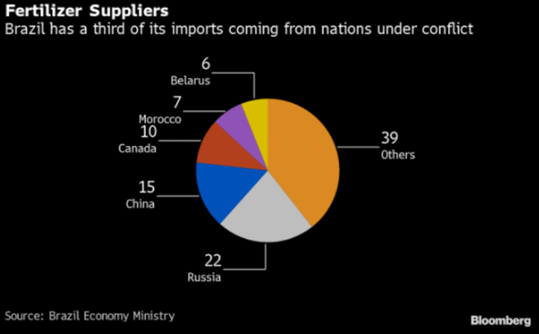

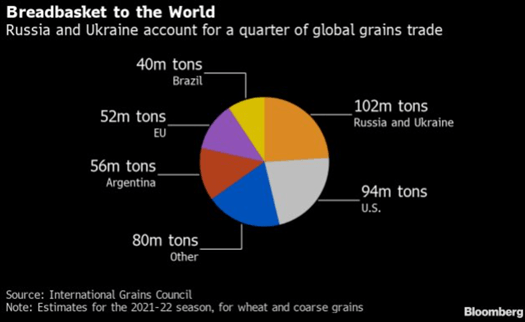

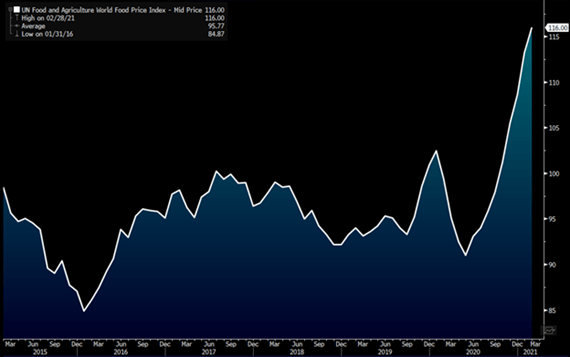

Food prices are now at record levels, and have “officially” taken out the peak that we saw in 2011. The price of grains is only going to go higher as a huge provider of food to market is taken out by a war. Russia-Ukraine are major suppliers into the market, and they also provide a sizeable amount of fertilizers. Insufficient domestic supplies of crop nutrients have been a thorn in the side of Brazil for decades, with the agricultural superpower importing about 80% of its needs. The Ukraine war has seen Brazilian farmers struggle to buy fertilizer, fueling a debate on the exploitation of potash reserves in the Amazon, including on indigenous lands.

Brazil sources a large amount of their fertilizer needs from Russia making these statements concerning: Russia is urging the country’s fertilizer producers to halt exports in a move that could send soaring global fertilizer prices even higher. Russia’s Ministry of Industry and Trade recommended domestic fertilizer producers cut volumes to farmers due to delivery issues with foreign logistics companies, according to a Friday statement. The country, which has been facing increasing international sanctions since invading Ukraine, is a major low-cost exporter of every type of crop nutrient. This would also hit Europe hard because they provide a significant amount of product to the rest of the continent as well.

Russia can’t supply farmers in Europe and elsewhere with contracted volumes of fertilizers because a number of foreign logistics companies are sabotaging deliveries, Russia’s Industry and Trade Ministry said Friday in a statement.

- Given the circumstances, the ministry recommends a halt to fertilizer exports

- Russian farmers will receive volumes of fertilizers they need

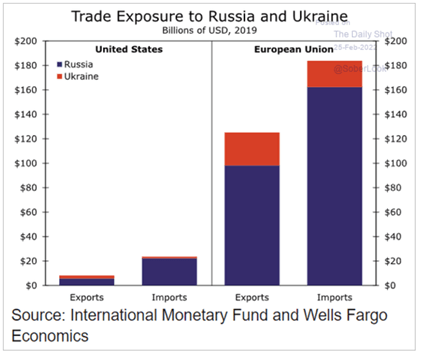

Russia trades a signficant amount with Europe with mainly raw materials and energy flowing into the EU whole the EU sends finished products back to Russia. The U.S. exposure is smaller, but still significant in the areas we import- IE oil and diesel.

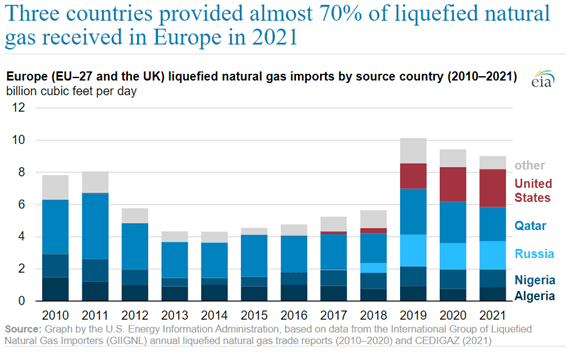

Russia sends natural gas to Europe by way of pipe but also by LNG. There isn’t enough LNG in the world to offset the loss of Russian natural gas to Europe, which leaves them in a tough spot to backfill. This is another reason they are in active discussions with Japan to take buy additional cargoes from them in order to secure their storage situation.

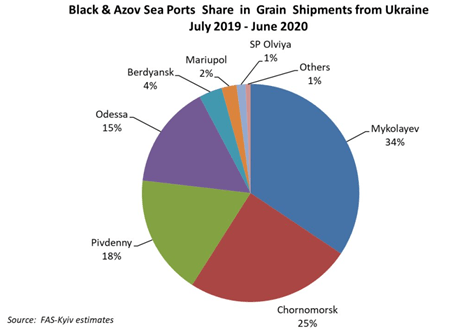

The food impact will be a huge issue given most of these ports are under siege/attack and won’t see any new exports. Ukraine is typically getting read to plant this years crops in the next 30 days, which is highly unlikely to happen even if Putin pulls all of his troops out of the country. This will leave the whole world short grains- not just this year- but also next year. We have already had droughts in Brazil/Argentina causing those estimates to fall again.

Russia and Ukraine make up the largest amount of global grains in the world. By losing one if not both, will put the world on a very scary path of broad shortfalls and another big driver of inflation in the market.

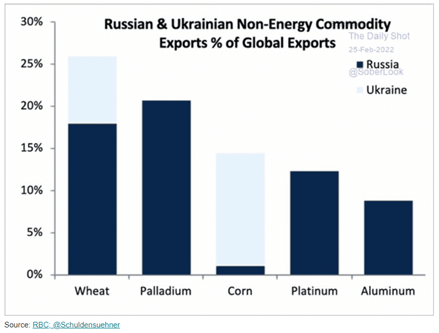

Russia also accounts for a huge amount of other products such as palladium, platnium, and aluminum to name a few. All of these base metals were already facing tough supply chains and bottlenecks, and the loss of the below volume will only exacerbate a bad situation. The world has yet to recover from the COVID bottlenecks and throwing in the Russian issues just makes it exponentially worse.

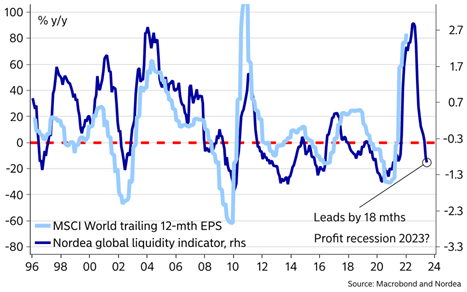

The underlying shortfalls will only drive inflation higher at a time when global central banks are raising rates. We have governments cutting stimulus and facing a spike in costs as they try to maintain subsizies for petrol in their countries. Essentially all countries in ’20-’21 had governments spending freely to support the economy, so it is difficult to see how they can maintain an easy fiscal policy as debt mounts and inflation spikes. Many budgets are going to get blown apart by the spike in energy and food. The below chart just shows how tight liquidity is getting and how that is going to be a big headwind for corporate earnings. It will weigh on margins and underlying profitability.

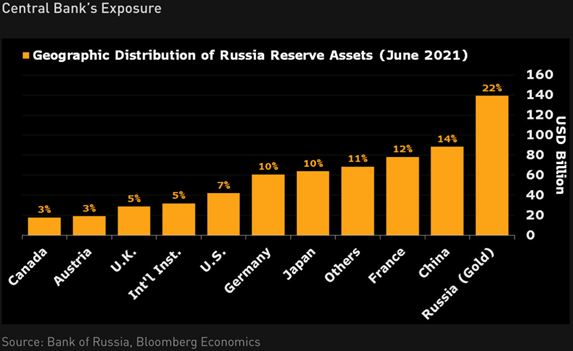

The Russian central bank is going to struggle to recover their foreign reserves. They probably started to pull some back ahead of the invasion (assuming Putin told them) because this chart is from June 2021. Central banks don’t keep their FX reserves purely in country because each bank leaves exposure in key areas so that their country and companies can do business there easier. This allows for an easier conversion of FX and ability to access those financial markets. Many of these countries have frozen their assets, which limits the ability for Russia to do business around the world.

China is watching this very closely because they need extensive access to the global financial markets, and what is happening to Russia would cause a huge problem for the functioning of the Chinese system. China has been trying to keep inflation muted to try to stimulate local spending. So far- China has failed to stimulate local consumption, but it remains a key focus for the country. They keep saying it will happen, but they have been unable to actually achive it. The most recent comments of their targeted approach is below:

In a press conference Tuesday, Commerce Minister Wang Wentao said he is will aware of the problems:

- “The downward pressure on consumption is still great, and pressure to stabilize consumption this year isn’t small.”

- “This year the pressure [on foreign trade] is going to be huge, and the situation is really complicated.”

Wang’s promise: The Ministry of Commerce (MofCom) would do “everything possible” to promote consumption.

As for exports: One of the challenges facing China is that 2021 was a banner year for exports. That high base will be difficult to match, let alone build on, particularly given:

- “The supply of raw materials and bulk commodities has not returned to normal.”

- “Labor and materials shortages continue to plague traders.”

- “The cost of raw materials and freight remains high”.

Wang added that some small firms’ negative outlook has undermined their willingness to accept new orders.

Get smart: We’ve been saying this for a while. China’s export machine is set to take a hit this year as developed economies emerge from the pandemic.

- That means less spending on home goods made in China, and more on services offered locally.

Get smarter: Although Wang and other officials realize they need to do something, Beijing has yet to come up with a solution for sluggish domestic consumption – which will need to take up some of the slack as exports decline.

- Common Prosperity – Xi’s initiative to reduce inequality – is designed to eventually boost consumption by giving households a greater share of the economic pie. But that’s a long-term structural reform and does nothing to get consumers spending today.

What to watch: If Wang and co. have some consumption-boosting measures up their sleeves, we will likely get an indication at the Two Sessions, which start on Friday.

The CCP remains focused on trying to drive additional support for small businesses. We have another group of comments from the Minister of Finance. The CCP has been targeting this are for the economy for stimulus, but has failed to drive up any real support.

On Wednesday, Minister of Finance Liu Kun penned a front page column in Study Times, the Central Party School-affiliated newspaper.

ICYMI: Liu has been on a tax-and-fee-reductions roadshow of late.

Last Friday, he wrote an op-ed in People’s Daily highlighting a variety of fee cut and subsidy proposals.

At a Tuesday presser, he announced that large scale tax reductions are coming this year.

Liu reprised his refrain in Wednesday’s column, saying policymakers would look to reduce the tax burden for:

- Small and micro enterprises

- Individual entrepreneurs

- R&D

Industries that have been particularly hard hit by the pandemic, like the service sector

Don’t worry though, all those cuts won’t leave government coffers high and dry (Study Times):

- “Although tax and fee cuts reduce current fiscal revenue, they will increase investment, confidence, and motivation.”

- “[Tax cuts] will also support stable and expanded employment and ultimately help sustain economic growth while expanding the tax base.”

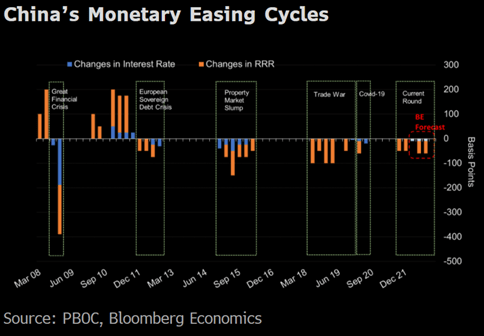

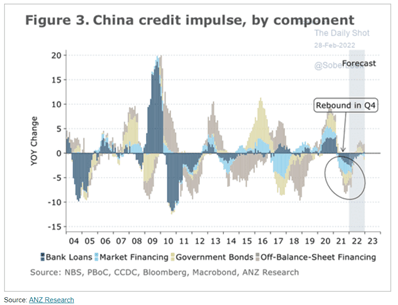

The PBoC has been increasing liquidity over the last few weeks, but we haven’t seen much reaction within the country. The biggest issue remains- they have already been using a lot of stimulus throughout the last 10 years without ever really tightening. We have seen liquidity ebb and flow, but from the persepctive of interest rates, RRR, and taxes- it has been a one way cut.

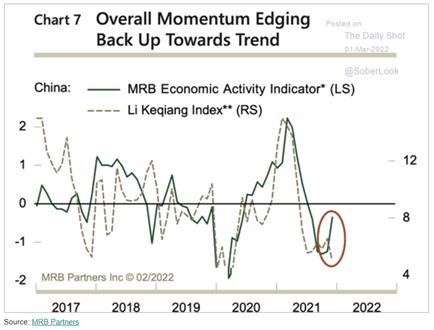

We have seen some movement, but it still remains muted. As prices spike- for both industrial and local consumers- the pain will be broad and the government will struggle to cover some of these costs.

Momentum is picking up, but as prices spike it will cool off the movements higher. It won’t cause them to reverse, but we will see renewed pressure on the economy-especially China. They will struggle to eat those costs as the industrial sector has to pass more on to the export and local markets.

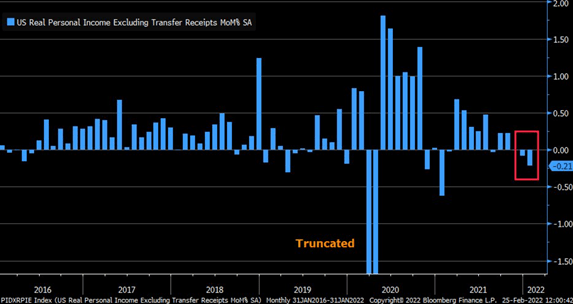

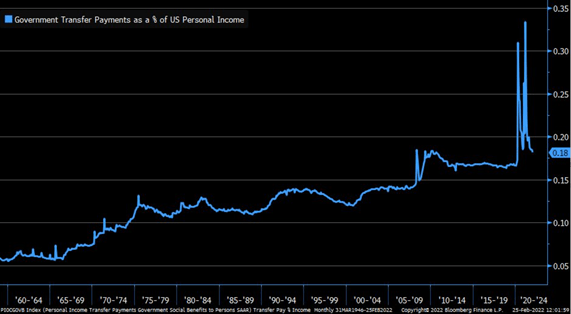

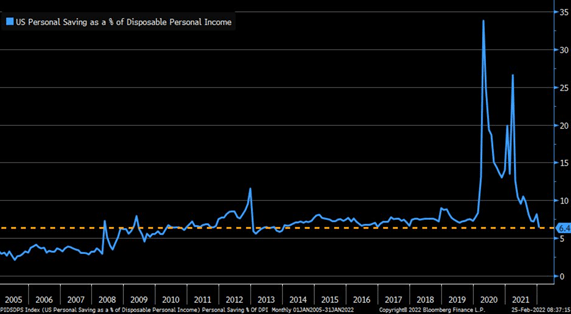

The U.S. market is going to struggle to absorb additional price increases as wages fail to keep pace with the recent moves on inflation. We are still at the beginning stages of this price move with more pain yet to come. This is all coming as presonal income excluding government transfers is negative and savings rates have moved to the lowest level since 2013.

Savings rates has collapsed to 6.4% which is the lowest since 2013.

The U.S. isn’t the only place this is going to bite hard- but Emerging markets remain the most exposed. We are now above the levels from 2011 that sparked the Arab Spring or as some call it “The Peasant Uprising.” This is why we called out that geopolitical risk was going to grow… and we are only in 2022! Here is the article from Feb’ 21.

WHAT COMES ON THE OTHER SIDE OF COVID19?

January 5, 2022

By Mark Rossano (Originally published Mar 19th, 2021)

As the world starts to awaken from the COVID19 pandemic, we are quickly going to see the problems that existed prior to 2020 come roaring back with a vengeance. Historically, social unrest and uprisings have often followed widespread illness, and this does not bode well for a global economy that was already not in a good place in 2019. Those countries with the least economic support (Emerging Markets and Low-Income Countries) face the greatest likelihood of problems, as stimulus is harder to achieve on a monetary and fiscal level. The U.S. and other Developed Markets have the luxury of borrowing, and with the U.S. Dollar as the reserve currency of the world, we have gotten drunk on cheap liquidity (which we have discussed in previous articles). We have tried to stop the business cycle by stimulating the market with trillions of dollars globally, which has just made the underlying issues of social mobility and inequality exponentially worse.

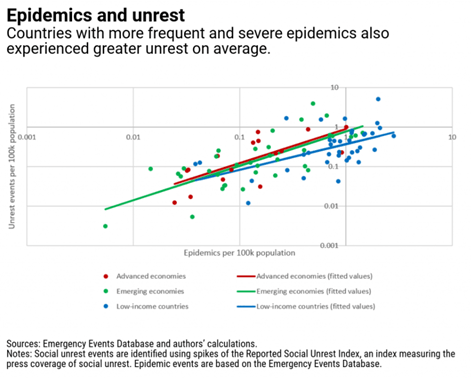

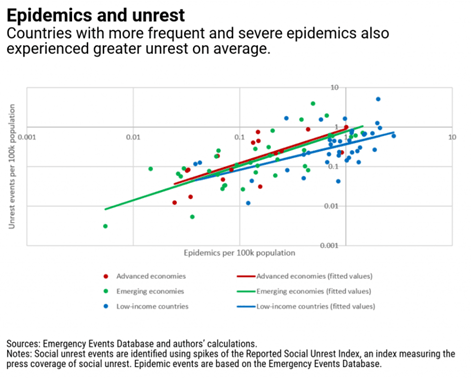

I want to look at Emerging Markets and Developing Nations because we know problems arise after epidemics, but what about a global pandemic? We haven’t had something on this scale since the early 1900s, and while there have been localized issues with illnesses such as SARs, MERs, and Ebola, the U.S. and Europe have been mostly spared—allowing for relatively stable trade, even as disruptions hit different corners of the world. Being the largest importer globally, the U.S. never stopped buying through those epidemics, but now we are facing a different economy on the other side. One with compressed wages, elevated unemployment, and rising inflation that will impact buying power. We will also see a change in consumer behavior as flexible work schedules are introduced and e-commerce purchases shift buying patterns. This will impact trade and consumption for an extended period and limit the recovery in Emerging Markets. Citizens are currently facing a lack of subsidies, job prospects, inflation, and food shortages that just throw jet fuel on the forest fire that was the economy prior to COVID. The below charts put some of this into perspective. It isn’t surprising to see that population density matters since there are less goods and money to spread around. Another key factor in assessing risk is Time. We may be returning to some normalcy, but as people go longer without food, work, or other basic needs, anger increases and the chance of unrest goes up exponentially. There is always a lag in the “anger” or expression of frustration as people are unlikely to protest/riot at the peak of a pandemic (or in this case, COVID19). Typically, poor nations are exposed to more disease and epidemic spreads, which keeps their economic development running in place and exhausting government support quickly. We are now facing a rise in food shortages and cost, and when people can’t feed their families, desperate actions and measures are taken.

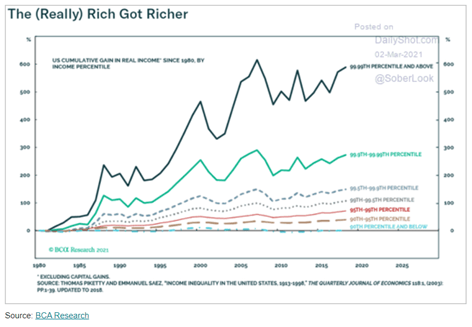

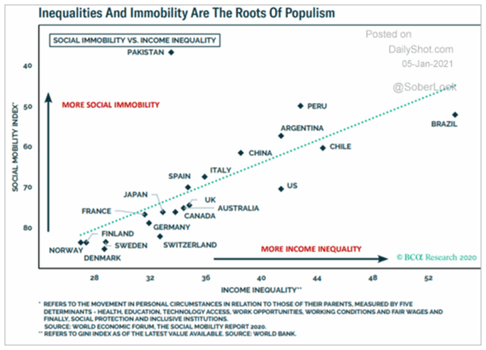

The world has been facing a rise in inequality and social mobility long before COVID19 ever entered the lexicon. This is where the “Developed Nations” come into play, as wage compression has been a key factor in creating inequality. Look at the recent expansion in U.S household net worth in Q4’20: up $6.9T, but equity holdings increased by $4.9T, with real estate adding $1.5T through price appreciation, home improvement, and cheaper rates/refinancing. So $6.4T was created by holding a portfolio of assets, leaving the expansion for everyone else at $500B . . . how much was stimulus to the poor again? The top 10%–20% have the benefit of investing across inflating assets, but if you don’t have spare cash to put into a house or stock portfolio, you are left with whatever job you can get and stimulus the government throws your way. The U.S. at least has the benefit of trillions in fiscal and monetary stimulus, but since we have been stimulating the economy since 2008, inflation has been waiting in the wings.

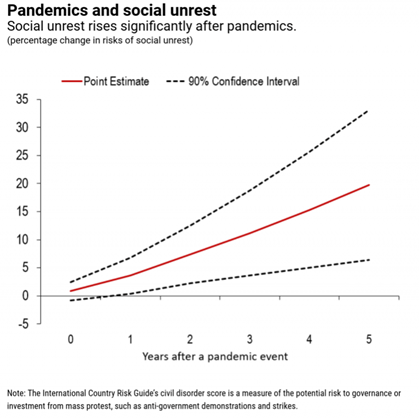

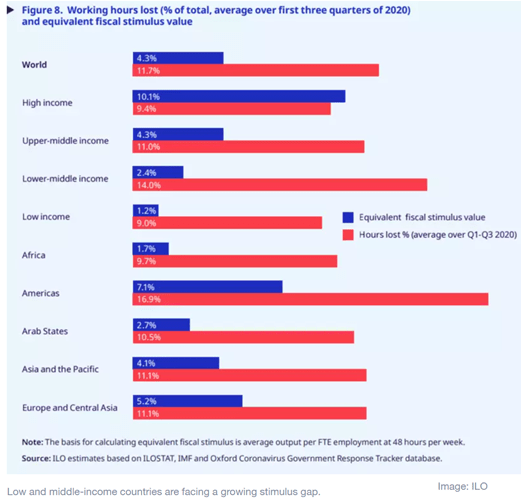

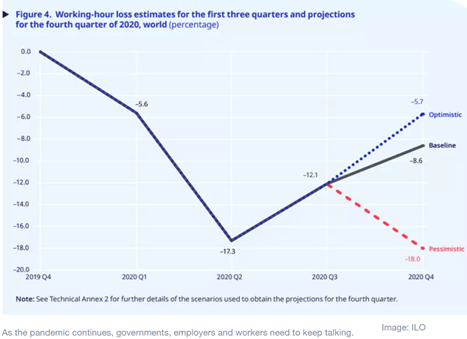

When looking at the “Pandemic and Social Unrest Chart” you’ll see that as a country moves farther along the dotted line, the pressure mounts on the local citizens that are trying to improve their social standing. While global poverty saw a steady decline, food insecurity has become a broader problem as the population grew and grains yields remain stagnate. Wage compression has impacted social mobility across all economies: Developed and Emerging. The reduction in salary and benefits comes from the elevated level of unemployment and the duration that people have been out of work. The longer someone is unemployed, the less money they will accept to re-enter the workforce—especially if they are changing careers. Job openings are back above pre-COVID levels in the U.S., but yet companies are reporting that jobs are hard to fill because it either makes more sense for candidates to collect unemployment benefits + stimulus, or they have the “wrong” skillset. The below chart puts a value on the amount of money lost—the “red bar” highlights hours lost, with the lower-middle income and low-income brackets getting absolutely destroyed. Global debt is at historic highs. Countries are issuing debt at massive rates to provide stimulus for the economy, but the interest expense is now rising as yields push higher. The cost of this debt has risen since the below chart was created; yield curves price in more risk and inflation has risen on a global level. Debt requires a buyer . . . and who is the buyer of last resort? Or rather, when does that paper have to stop because demand is filled? If it is a central bank buying, when is inflation seen to be out of control and needing to be reined in? So the blue bar estimates what fiscal stimulus it would take to close that gap as of Q3’20—but how much money is available to bridge the gap? Is there a job on the other side, or will the individual have to change careers? Working hours have been lost around the world with little chance of a near term (or even long-term recovery). Companies were already bloated in 2019 (hello zombie companies!) and technology CAPEX has increased, resulting in further wage reductions. Automation has replaced or streamlined work processes, limiting total earning potential. This inherently impacts the middle- to low-income earners the most, as some (if not all) of their job function is replaced, outsourced, or done by less people working longer hours.

If a company hires someone with a limited skillset, they will offset the loss of efficiency from on-the-job training by reducing total compensation. This reduction in salary is being stressed further as inflation hits wallets and the costs of everyday life drive higher. The below chart also shows that more employees who want full-time work are only getting part-time opportunities due to the limitations in the current job market.

This pain is spread across the world, but it’s clear that those in the middle of the pack or lower seem to be getting left behind. It takes time to get discouraged and disenfranchised because nothing happens overnight, but the stress placed on the global economy by COVID19 has exacerbated the problem. Companies have found an “easy” way to cut personnel and an excuse to not hire them back, or if they come back, they are at depressed wages. Now with inflation kicking into high gear—and more importantly, food prices tightening—the stakes are really going to rise in the geopolitical theater.

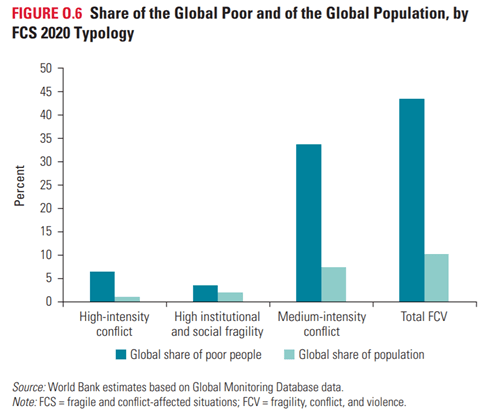

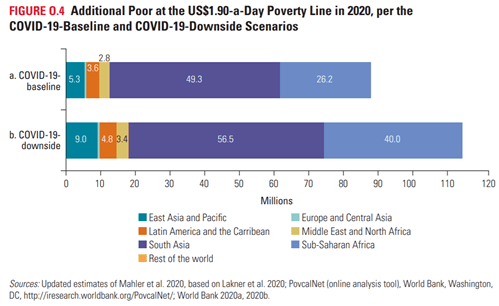

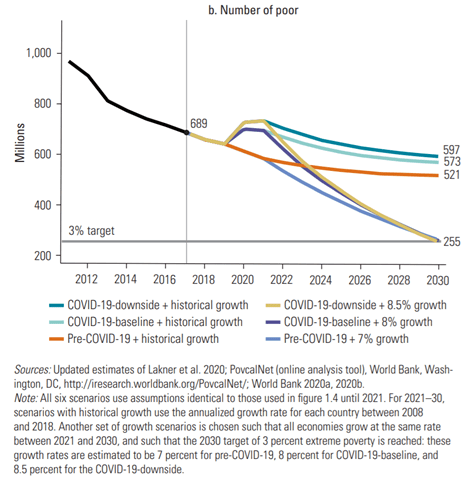

The number of global poor has increased the most in “medium-intensity” conflict locations. So if you have a group of people that were already at the front end of mounting unrest, what does a global pandemic do for you? How much support can these countries provide if they were already facing struggles at home? The “size” of those deemed as poor is erasing 10 years’ worth of progress. This will take years to adjust back to previous levels given prolonged issues in global trade and underlying pricing that will increase the cost of living. Regions already facing a problem will be driven into overdrive.

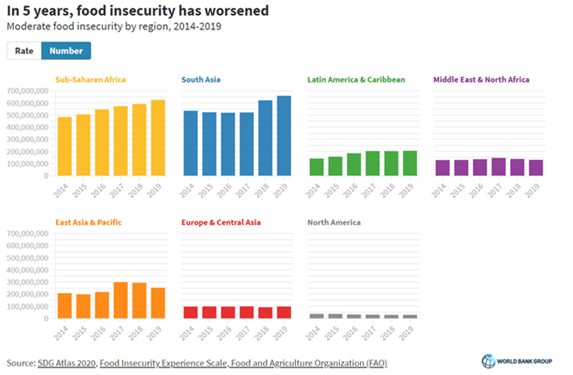

Basic needs are the crux of survival, and economic expansion can’t begin until people not only have enough to live, but excess that can be stored or sold to allow for growth. For example, if you are worried about your next meal, will you focus on growing a garden / foraging for food, or sitting at a library to study to become a doctor, engineer, writer, or another skilled job? Food insecurity has become a big problem around the world, with Africa and Asia seeing a steady rise in basic needs not being met. The below chart is from 2019, so when we factor in prices that are now back to 2014 highs, the pain is just getting worse. 2014 was when global food insecurity really started, and now that prices have pushed back to decade highs—alongside a global pandemic impacting salaries and subsidies—the pain is just beginning. It is important to note that even without COVID19, the world was already facing several “Biblical”-sized locust swarms, droughts, floods, swine and avian flu, army worm infestations, among other disruptions that were causing yield drops. COVID19 was the cherry on top that has made a bad situation much worse—limiting the movement of migrant workers, delaying plantings, harvests, and bottlenecks at ports. We have seen an increase in acres planted, but weather hasn’t been cooperative, delaying key planting across places like Latin America. These adjustments take seasons, and with China absorbing massive amounts of grains in the market and dealing with a new round of swine flu driving up prices, poor countries will be left paying up for goods to feed their people. Nationalism will also become a bigger issue as countries withhold exports, managing volumes and pricing, to make sure their citizens have enough to eat. We saw evidence of this at the outset of the pandemic, and restrictions still remain in place with export quotas and rising tariffs.

UN Food And Agriculture World Food Price Index

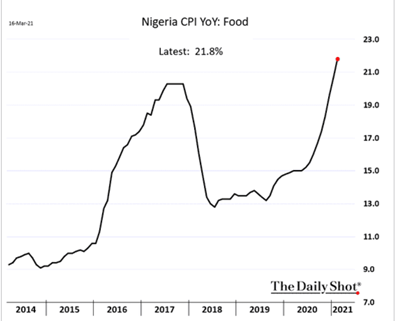

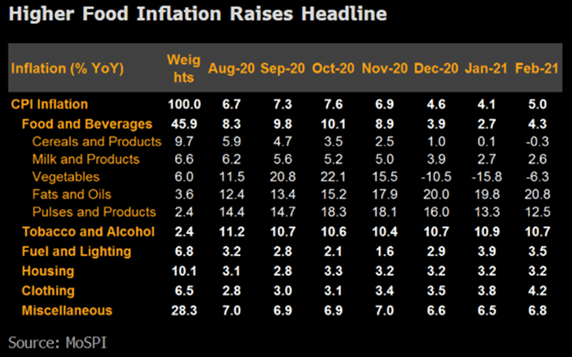

The global rise in grain prices has resulted in huge spikes of food inflation, with the below charts highlighting just two examples in Nigeria and India:

India Inflation Breakdown

The rise in inflation and inherent costs—alongside falling wages—has only intensified the extremes of poverty, with more people being added to the “$1.90 a Day Poverty Line” continuously throughout COVID19. The longer people reside below these levels, the more anger builds up against their situation, and blame gets passed around. We have already seen food riots and general uprisings in Africa (most recently Nigeria), the Middle East (Iran), and Asia (Myanmar), and we aren’t even fully out of the pandemic. Pain, despair, and anger has been bubbling beneath the surface for years, and now the match has been lit.

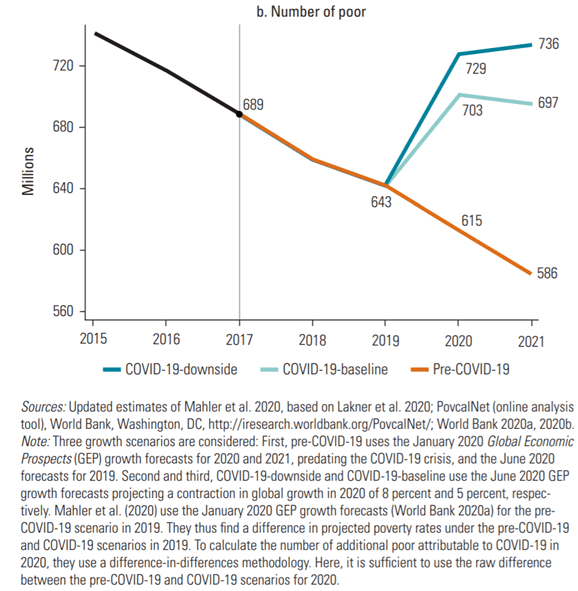

Globally, the number of poor is broken out into several categories based on the “depth” measured by USD payments per day—with the lowest being $1.90 and highest just below $6. The World Bank has seen the global poverty figures declining steadily over the last several years. Since 2019, the trajectory started to shift and COVID19 sent us on a completely different path higher due to lack of earnings potential. Now, with the U.S. 10-Year Treasury Bill shifting higher, the cost of borrowing has risen, limiting the underlying stimulus a government can provide through subsidies and economic incentives. We are already seeing fuel costs rise globally with little ability for governments to protect or limit the rise. This will only exacerbate underlying issues across food availability and basic needs. Sadly, the below chart illustrating global poverty is not painting the full picture. Their criteria for classifying “poor” does not include levels seen in Developed Countries—who are having their own issues with food security and populations falling well below the poverty line designated by the country. The U.S. is no exception to the pressure, as weekly jobless claims throughout the pandemic have outpaced the worst day of the financial crisis (665k jobless claims in March 2009). We have the benefit of borrowing, but as the U.S. taps the debt market at a greater rate and inflation fears rise, so do our interest rates. As our rates go up (10-year is typically the global “risk free” benchmark), countries are finding it harder (and more expensive) to access the markets. This is why I believe we will see those “Number of Poor” values continue to shift higher and reach the “downside” case—especially in Africa and Asia. In the United States and Europe, the extremes of destitution are vastly different, but that is not to say that people aren’t reaching the same levels of despair and “hopelessness” as other people in poverty around the world.

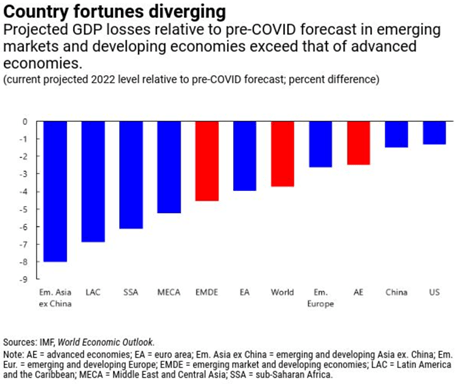

The hope is to continue to pull people out of poverty by 2022, but the baseline shift (measured by the light and dark blue lines) demonstrates the lasting effects of COVID19 on the global economy. Once we factor in the prosperity shift, we have to look at food security, age of the workforce, and underlying opportunities for advancement. The Middle East and Africa have a young workforce and some of the highest unemployment numbers for the key working ages of 16–35. This is when Generational Dynamics come into play as the next generation looks to enrich themselves and build a life/family. When that isn’t achieved, with little chance of change, this group is more likely to take to the streets to drive some form of change. We have seen protests across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, with more to follow as pressure remains across the system. Europe is facing another wave of COVID19 cases alongside Latin America (Brazil), and with continued hurdles with the vaccine rollout, the pressure on economic activity will be prolonged. The longer the Developed Markets remain capped, the worse off Emerging Markets will fair, as major economies are the main buyers of raw materials and semi-finished goods. The limitations on demand prohibit the movement of capital into poorer nations and stress the balance sheet as foreign reserves dwindle. This leads to increased inflation fears, limiting the ability for the central bank to cut rates and the government to borrow.

Here is just one example, below: Nigeria is facing food riots and increased political pressure as a third of the 69.7M workers either haven’t worked or have fallen to below 20 hours a week since the pandemic started, while 15.9M have worked less than 40 hours a week. If you want something more for your family and are willing to work for it . . . how can you achieve that with limited opportunity and part-time work?

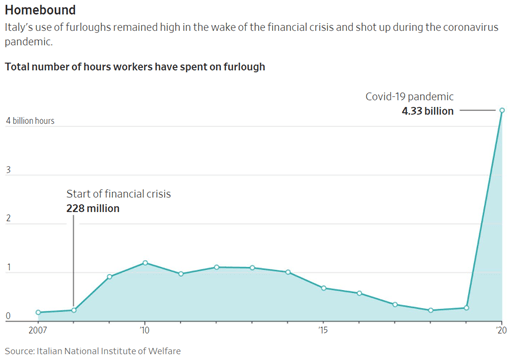

At the Developed Market level, millions of workers have been furloughed and are being paid to do nothing. Germany, France, U.K., and Italy are paying workers’ salaries until the economy normalizes so employers can avoid large-scale layoffs. They are looking to avoid the “social cost”—or unrest—that would result from that upheaval, but Emerging Markets don’t have that luxury. “Italy has been doing that for decades, turning what was supposed to be a short-term program to save jobs into a permanent fixture. Now, an especially weak economy and a glacial rollout of vaccines in the EU mean millions of workers will remain furloughed well into 2021.” The rise in COVID19 cases and pause in vaccine rollout will just increase the need for stimulus and underlying support. “Indeed, pandemics can set off a vicious cycle of economic despair, inequality, and social unrest. Using econometric analysis, we show that past major pandemics led to a significant increase in social unrest in the medium term, by reducing growth and increasing inequality. Higher social unrest, in turn, is associated with lower growth, which worsens inequality, forming a vicious cycle.” These characteristics are a problem given the low growth we have experienced over the last several years.

Wars don’t typically happen during robust economic growth, but rather when there is an event that creates prolonged impacts to basic needs. If I can get a job, afford shelter, and feed my family, why would I go fight a war? But would you feel differently if you were watching your children starve? The below chart is just one metric of evaluating growth, and we saw slowdowns creeping into key markets well ahead of COVID19. The International Monetary Fund “take[s] a closer look into this issue in a new IMF staff working paper by analyzing the effect of past major pandemics in 133 countries over 2001–18: SARS in 2003, H1N1 in 2009, MERS in 2012, Ebola in 2014, and Zika in 2016.” These were smaller pandemics. Now what happens after COVID19—a worldwide pandemic that sent the global market into its first contraction in over 20 years?

Emerging Market PMI (Purchase Manager Index)- source: Bloomberg and IHSMarkit

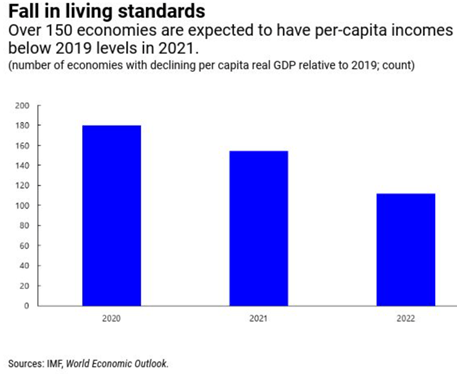

Living standards are dropping around the world with the extremes in Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa: all areas that were seeing an increase in uprisings before COVID19. A shift lower in GDP is just going to exacerbate an already terrible situation.

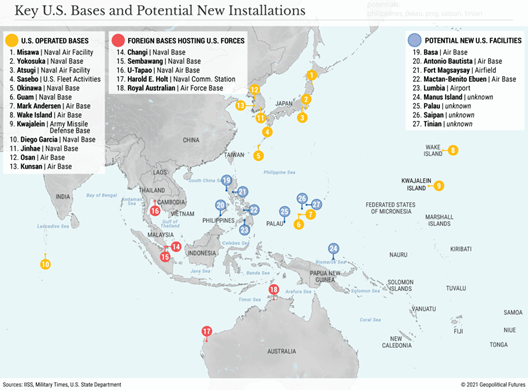

Developed Markets won’t be spared, either. The U.S. has already been experiencing riots in the face of an uncertain future. Living standards and general mobility in the U.S. has been falling, likely leading to more political strife. The gravity of it all has been somewhat kept in check by lockdowns and a hope for “better days.” But as COVID19 passes and people feel the sting of inflation and unemployment, the pressure will mount on governments, and calls for change will rise. The U.S. is addressing the rise in military pressure by looking to expand in Asia—accelerating our deployment of forward assets as depicted in the chart below. The U.K. is looking to expand their presence in Asia as well, especially after China’s violation of the Hong Kong treaty. India and China are already at standoffs in two strategic points of the Himalayas, with tensions rising. The U.S. is trying to win allies and influence to help manage China’s expansion in the region.

The “Spring Thaw” is approaching just as COVID19 cases are falling and vaccine rollouts are accelerating. We are living on the tip of a knife. Tensions are at the highest levels since the Cold War. We face a very bifurcated recovery, with the lowest three quintiles being left behind. The poor are getting poorer, and the middle class is being pushed closer to the poverty line as quality of life around the world is diminished. It just takes one incident (on purpose or by accident) to set off a chain of events that can’t be contained. This is why securing supply lines, solid allies, and trade partners will be pivotal for success on the other side of COVID. The problems we face were not caused by the pandemic, but rather magnified by underlying economic issues and growing food problems. This is a familiar trope: when the world becomes too tilted in one direction (as we have seen with the divide between rich and poor, with no growth or prosperity to promote social mobility), we face a rising chance of conflict. We have a long uphill battle ahead—one filled with difficult decisions and countless hurdles—but by relying on allies and supporting the business cycle, there can be light at the end of the tunnel.