The question of what lies ahead for oil markets remains more pressing than ever as we witness a series of interrelated developments across the global energy landscape. In particular, the pressure is mounting on OPEC as key players, especially Saudi Arabia, face increasingly challenging circumstances that extend far beyond supply and demand mechanics. As oil prices continue to dip, approaching their 14-month low, and the global economic landscape slows down, we must carefully dissect the implications for oil-producing countries, OPEC agreements, and the broader market.

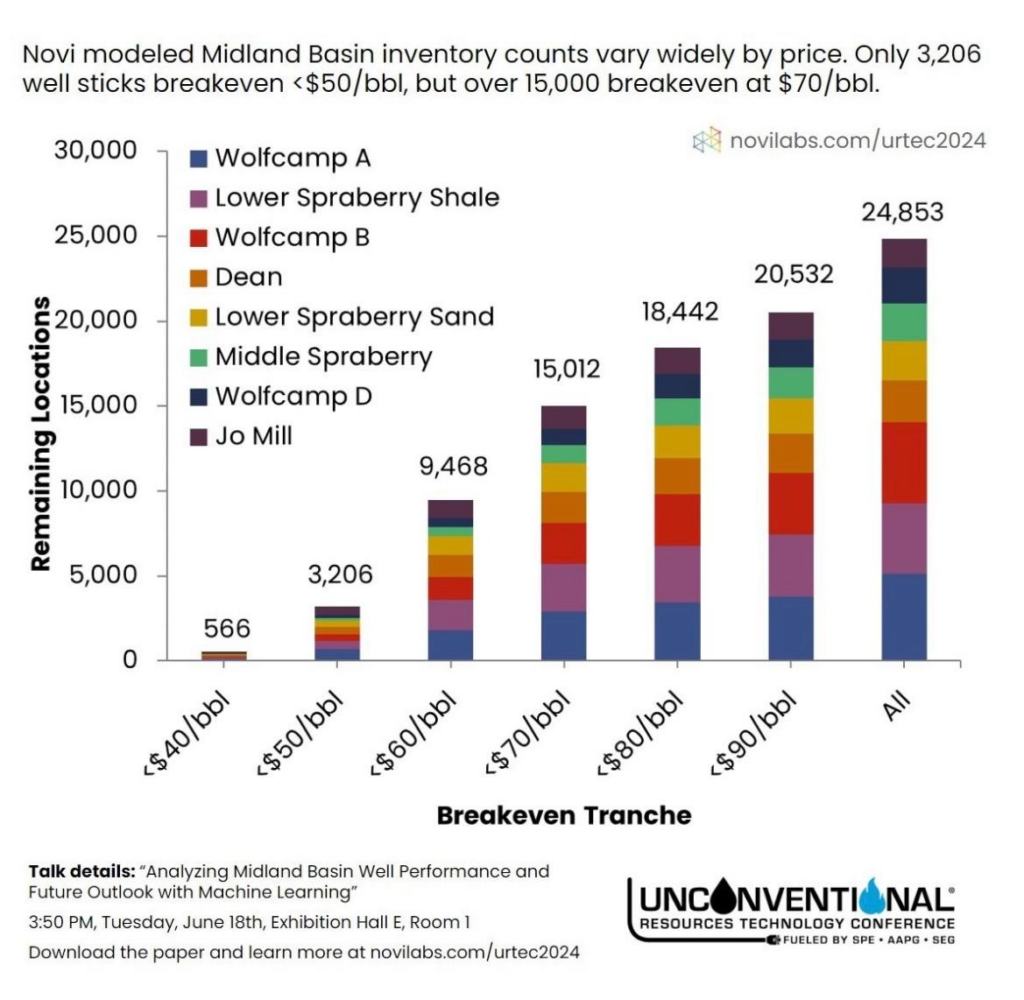

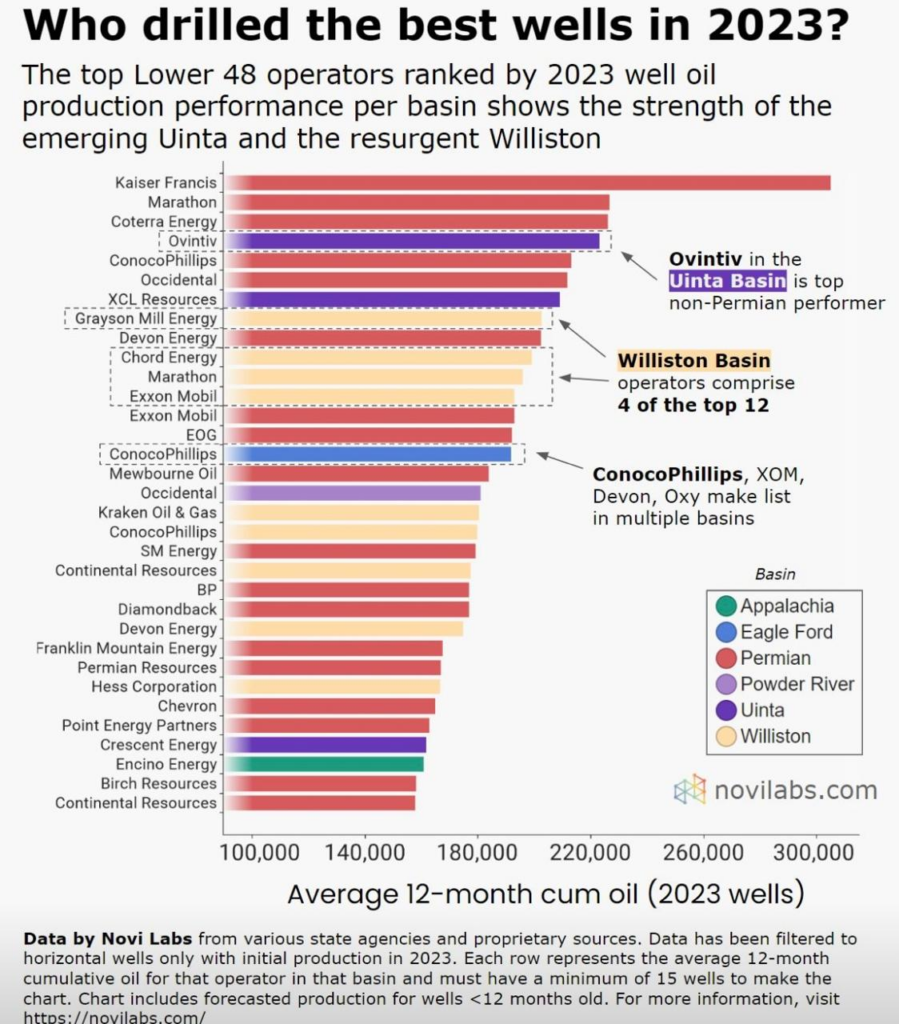

In recent months, the Permian Basin has continued to prove its vital importance to the U.S. oil industry. But how long can this go on? Data reveals that there are still approximately 25,000 undrilled locations left in the Midland Basin, a number that might seem promising but becomes problematic when considering the economic viability of these wells. Prices are a key factor. As oil hovers around $73 per barrel, a far cry from Saudi Arabia’s fiscal breakeven point of over $96 per barrel, it’s clear that not all of these locations in the Permian will be economically viable. It is projected that only fewer than 10,000 of these wells have breakevens below $60 per barrel, a stark contrast to the highest Tier 4 locations that demand $96 per barrel just to break even. As the oil price continues to linger at these lower levels, the profitability of U.S. shale becomes increasingly tenuous, which might explain the recent struggles for many smaller players in the region.

Turning our attention globally, Saudi Arabia is feeling the pressure. Their breakeven oil price has skyrocketed as the kingdom embarks on ambitious projects under Vision 2030, aiming to diversify the economy away from its overreliance on hydrocarbons. The most recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecast puts the breakeven figure for 2024 at $96.20 per barrel, a far cry from current Brent prices that hover around $73. The kingdom, despite its low production costs, faces a situation where even its considerable financial reserves and borrowing capacity may not be enough to cushion the blow from these prolonged low oil prices. Saudi Arabia has been able to tap the debt markets to cover its deficits, with its public debt rising from 3% of GDP in the 2010s to 24% today. However, it remains to be seen how long this can continue without significant repercussions, especially as non-OPEC supply, particularly from countries like Brazil and Guyana, continues to grow.

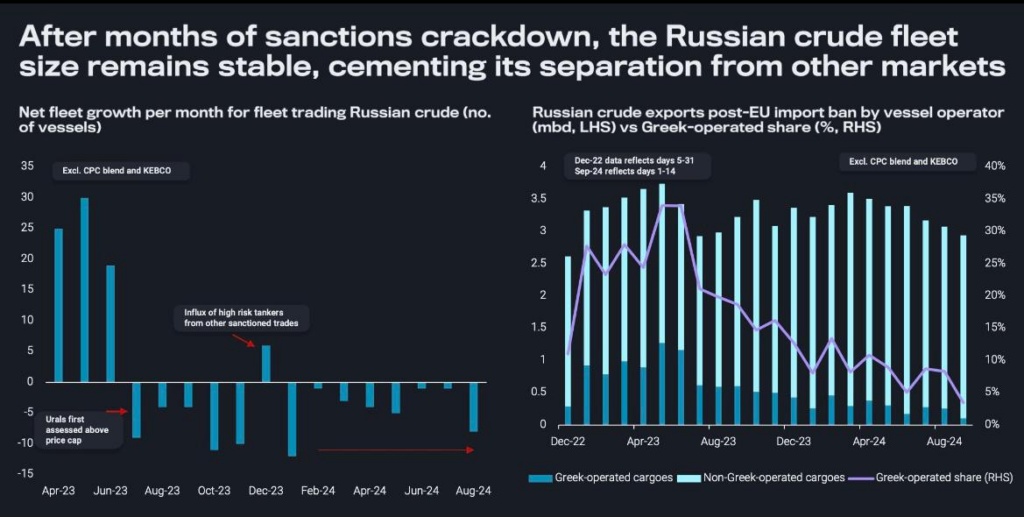

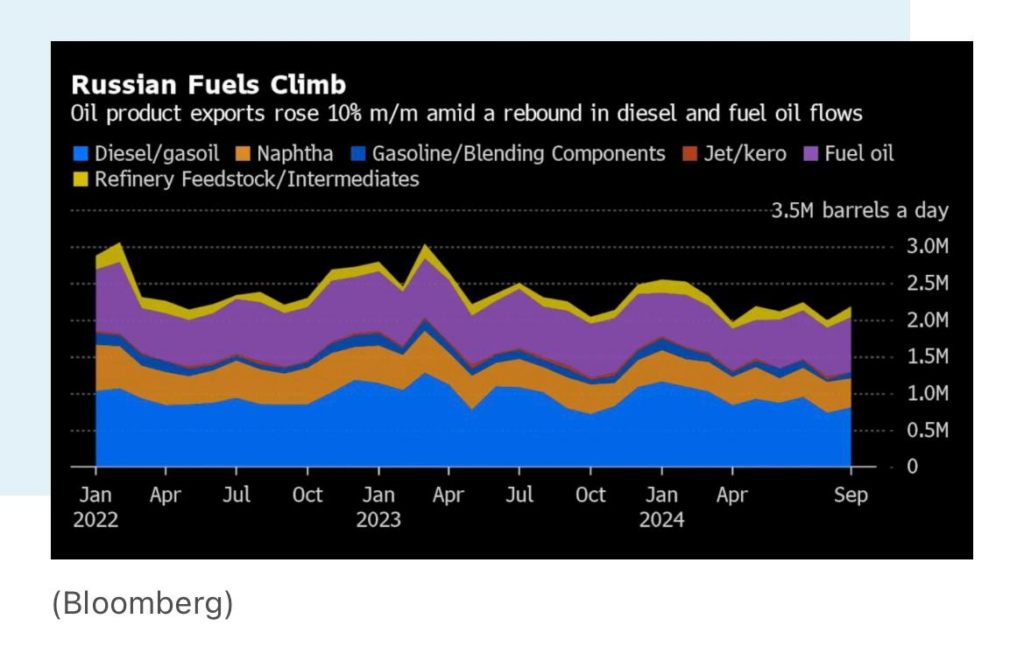

Compounding the situation is the resurgence of Russian oil product exports. Russian exports rebounded to 2.2 million barrels per day in September, up almost 10% from the previous month, indicating an upward trend in supply despite Western sanctions. This poses a problem for the already oversupplied market.

With Russia adding fuel oil and diesel exports to the global mix, the supply-side pressure on prices continues to intensify, particularly when key demand centers like China show signs of sluggishness. Russian oil revenues, while pressured, have managed to sustain themselves with the help of clever export rerouting, but the increased flows are adding downward pressure on global prices.

At the same time, the slowdown in global economic growth has not only impacted oil demand but also created a ripple effect across multiple energy products. Diesel stocks have been swelling at key global hubs, such as Amsterdam and Singapore, pushing distillate prices down and slashing refinery margins. In the U.S., inventories reached 125 million barrels in August, the highest for the time of year since 2021. Europe has been similarly affected, with stocks in the Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp trading hub reaching 2.2 million tonnes, the highest since 2020. With so much inventory on hand, refinery margins have plummeted, cutting the profitability of refineries and, by extension, decreasing demand for crude oil. Valero, the world’s largest independent refiner, has seen its share price drop more than 20% from its April high. Crack spreads, which measure the margin for refiners, have halved to $18 per barrel in Europe compared to $35 a year earlier.

While traditional giants like Marathon, Oxy, and ConocoPhillips continue to report strong results in the Permian, smaller players such as Kaiser Francis have surprised the market by leading performance with 305,000 barrels per well in their first year of production. This exceptional productivity hints at the long tail of high-performing wells in the U.S. shale sector, but also raises questions about the sustainability of this performance. Across Lower 48, 2024 is forecast to be even more productive than 2023, and some analysts believe it could be the most productive year ever for unconventionals.

The situation is not much better for OPEC+, which finds itself backed into a corner as it extends production cuts in the face of weakening prices. The organization’s recent decision to push back phased output increases until at least December 2024 only postpones the inevitable. The group had initially planned to increase production in October, but this decision has now been deferred as weak demand and high inventories wreak havoc on oil prices. In the worst-case scenario, if this trend continues, there is the potential for the current agreement to fall apart entirely as member nations start to cheat on quotas in an attempt to shore up revenues.

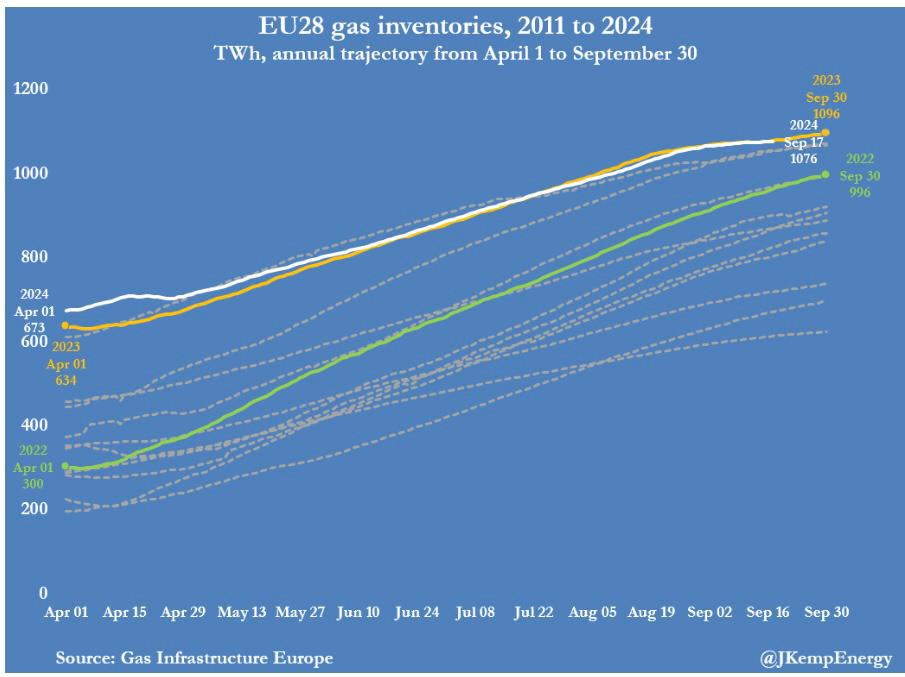

The backdrop to all of this is a slowing global economy, with major consuming regions, particularly Europe and China, struggling to revive industrial production. Europe’s gas storage is now nearly full, more than a month ahead of schedule, suggesting that demand is nowhere near what was anticipated. European gas inventories stood at 1,076 terawatt-hours as of September 17, a record seasonal high, further exacerbating the oversupply issues facing global energy markets. Similarly, in China, despite a recovery in crude imports in August, the industrial slowdown has kept demand tepid, raising concerns over future demand in the world’s second-largest oil-consuming country. With the U.S. Federal Reserve expected to cut rates by 50 basis points in the coming months, some may hope that cheaper borrowing costs will stimulate economic activity and increase demand for oil.