One of the major themes that has determined the direction of the global economy (and also oil prices) is the story of Chinese economy. There is a slew of indicators – some suggest stability, some improvement and others that points towards impending trouble. In many ways, the answer to the question if China’s economy is really in trouble depends upon the a) context it is being asked b) the timeline c) the perspective. This deep dive into China’s economy tries to analyze the question on all three points. If you are a business owner worried about the future direction of interest rates, or an analyst trying to navigate the important factors in global economy or even just someone who wants to learn what is and what will happen with the world in as we are 100 days away from 2025 – the story of China is extremely relevant for you!

Beijing has recently announced several measures aimed at arresting the decline, the real question remains: Are these moves enough to change the trajectory, or are they merely masking deeper, more systemic issues that have been building over time?

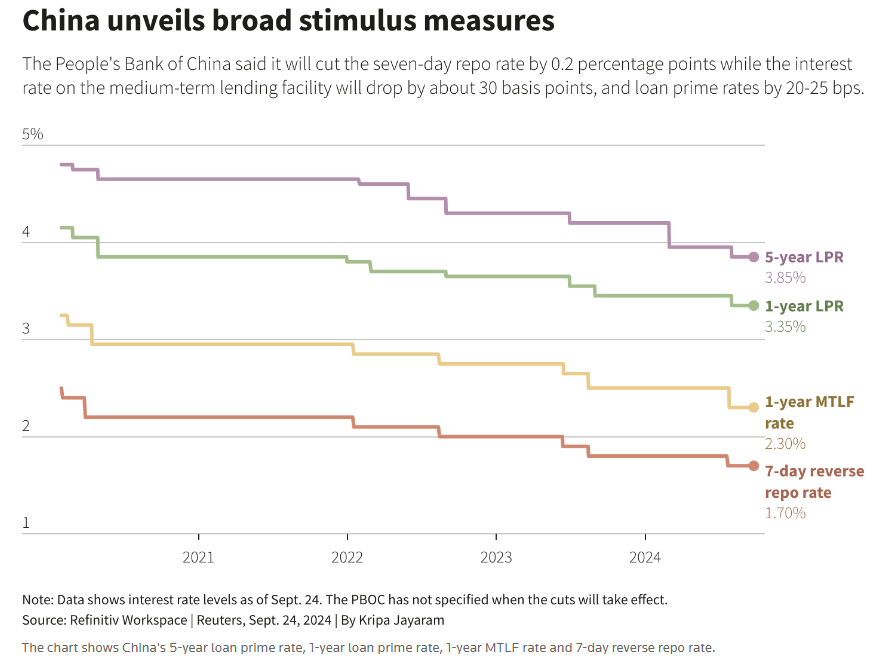

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has attempted to signal a path forward with a series of stimulus measures, including cuts to the reserve requirement ratio (RRR), a policy designed to inject liquidity into the financial system. In total, these actions are expected to release roughly 1 trillion yuan ($141.7 billion) into the market, offering short-term relief to an economy that’s been buckling under the weight of its own ambitions. In addition, the PBoC has moved to lower mortgage interest rates, a clear attempt to stave off further decline in the property sector—an industry that has been central to China’s growth story for decades

Yet these liquidity injections are at best a stopgap. Julian Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics has rightly pointed out that, while the PBoC’s moves are a step in the right direction, they are likely to be insufficient to spark a meaningful turnaround unless followed by more aggressive fiscal support. China’s broader economic problems run deeper than just liquidity constraints. What we’re seeing in China now is the culmination of years of economic policies that prioritized rapid growth and expansion over sustainability and balance. And those choices are catching up.

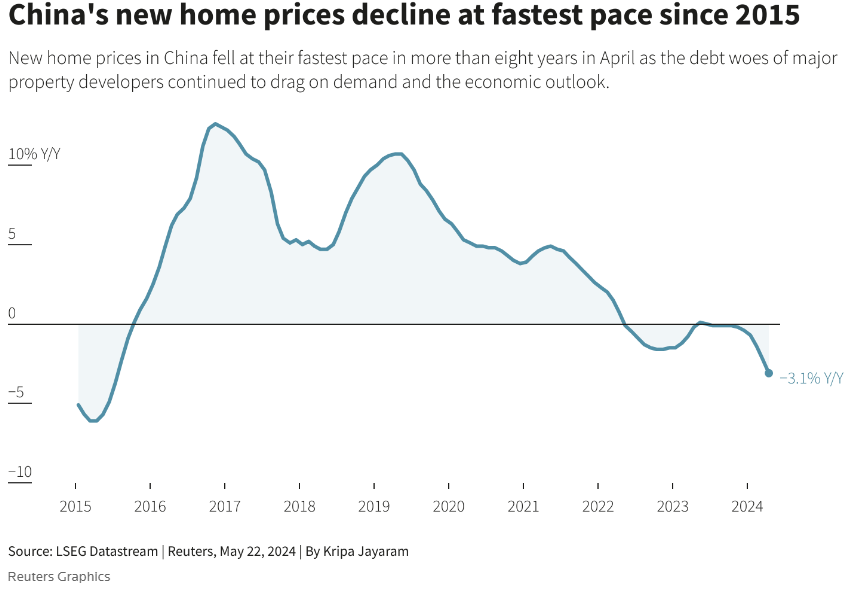

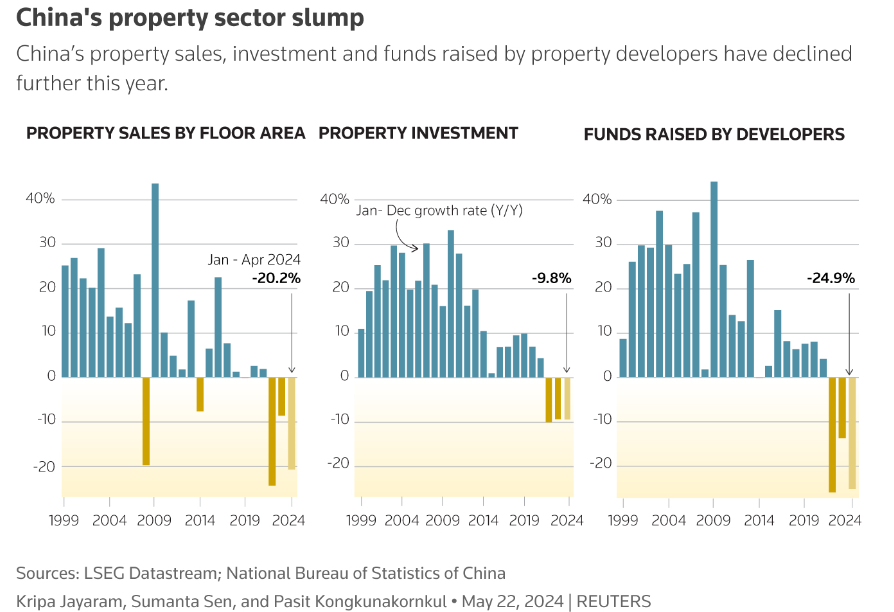

Take the property sector. Real estate accounts for roughly 25% of China’s GDP—an unsustainable proportion by any measure. The collapse of Evergrande, one of China’s largest property developers, has sent shockwaves through the economy. With over $300 billion in liabilities, Evergrande’s default is not an isolated incident; it’s emblematic of the wider problems plaguing China’s real estate market. Local governments have relied heavily on land sales as a primary revenue source, and with the property sector now in crisis, those revenues have collapsed. In the first seven months of 2024 alone, land sales dropped by more than 20%, a staggering decline for local governments already struggling under enormous debt loads.

To make up for the shortfall, local governments have resorted to squeezing more revenue from non-tax sources—things like selling state-owned assets and imposing fines. Nomura’s economists have highlighted the continued growth of these non-tax revenues, which jumped 12% during the first seven months of this year. But the reality is, this is a temporary fix. Local governments can only sell off so many assets or impose so many fines before they run out of options. And this reliance on opaque, non-tax revenue sources does little to inspire confidence in China’s longer-term economic trajectory.

Real estate prices falling and unfinished construction projects dotting cities across the country, confidence in the property market has plummeted. This has far-reaching consequences. For many Chinese, real estate is more than just a place to live; it’s a key investment vehicle. With property prices declining, the wealth effect that once supported consumer spending has evaporated, leaving households more reluctant to spend. And that’s not all. The ripple effects are being felt throughout the banking system, which is heavily exposed to the property market through both direct loans to developers and mortgages issued to homebuyers. Estimates vary, but recent data suggests that property-related loans could account for as much as 40% of total bank assets.

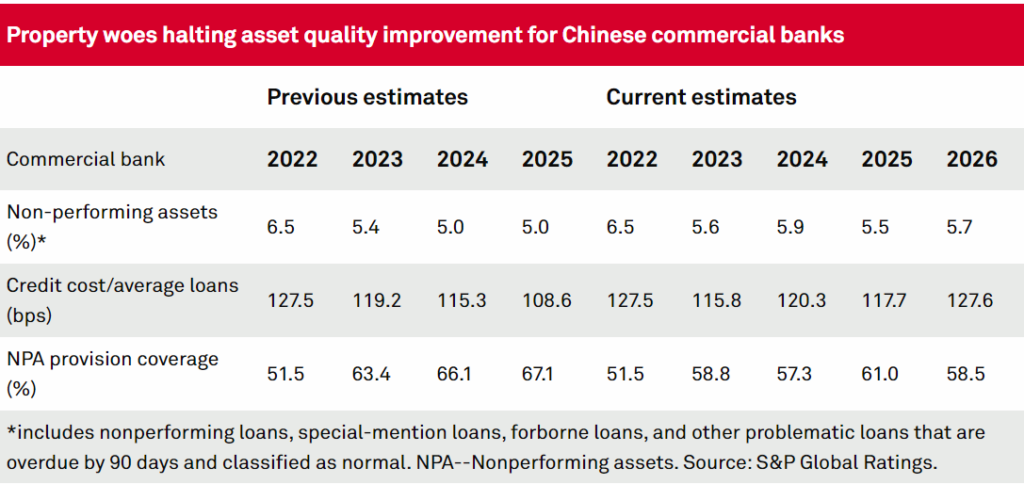

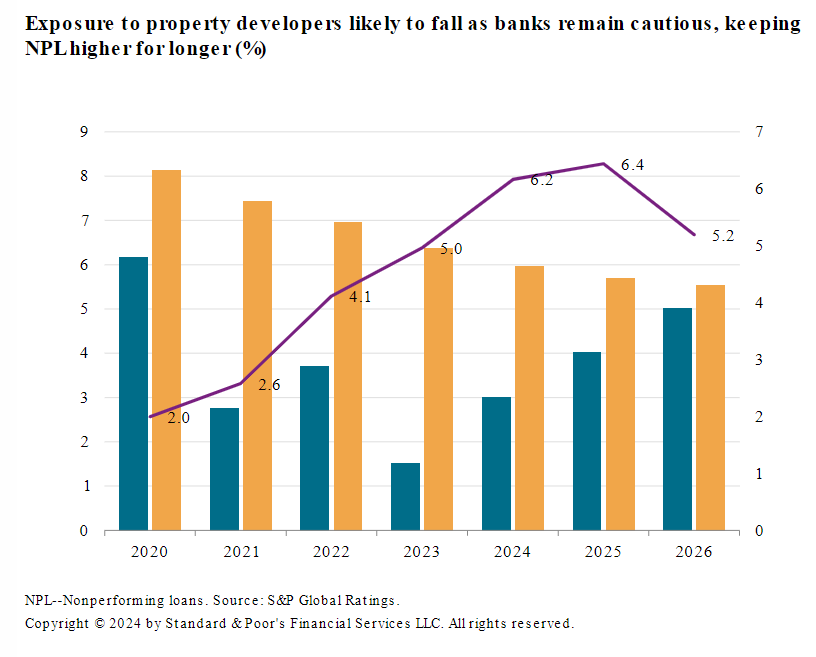

S&P Global has warned that the non-performing asset ratio in China’s banking sector could rise to 5.7% by 2026, up from an already troubling 5.6% in 2023. This stands in stark contrast to the Chinese government’s officially reported non-performing loan ratio, which is a mere 1.6%. The discrepancy between these figures raises serious questions about the true state of China’s financial system. The truth is, the official numbers don’t tell the whole story. Many of China’s banks, particularly smaller regional institutions, are facing significant pressure from mounting bad debts, and Beijing’s reluctance to fully acknowledge the scale of the problem could be a major obstacle to any meaningful recovery. If the property-related NPL ratio hits the projected peak of 6.4% by 2025, we could see increased strain on China’s banking sector, particularly among smaller and rural banks that do not have the financial buffers of their larger counterparts.

But the banks are expected to reduce exposure is likely to fall moving forward as they remain very cautious which will keep NPL higher for a longer time.

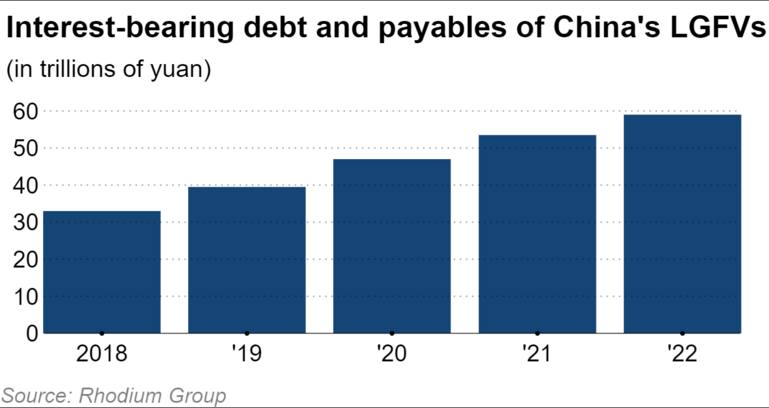

Adding to these challenges is the fact that local governments, which are already struggling with falling revenues, are heavily indebted themselves. According to S&P, China’s local government financing vehicles—off-balance-sheet entities that were used to finance large infrastructure projects—carry more than $10 trillion in debt. This debt overhang represents a massive risk to China’s financial stability. The problem is compounded by the fact that many local governments have been slow to respond to Beijing’s calls to take on more of the burden of addressing the property market crisis. Out of the more than 200 cities that were encouraged to buy up excess housing supply, fewer than 30 have done so, according to recent reports.

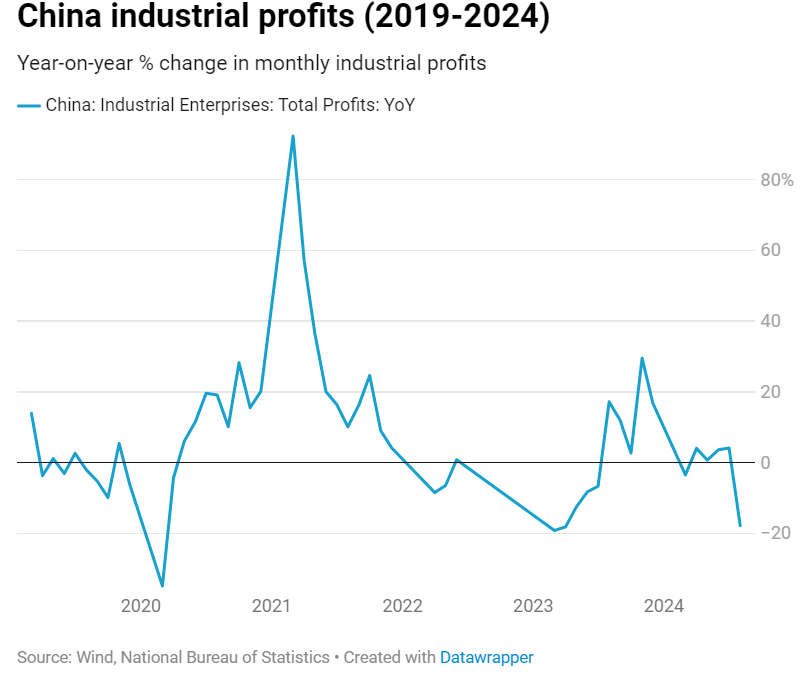

Meanwhile, China’s industrial sector is showing signs of strain as well. Industrial profits swung to a decline in August, falling 17.8% year-over-year, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics. This marks a sharp reversal from the 4.1% increase recorded in July, and it’s a clear signal that China’s broader economic slowdown is beginning to take a toll on manufacturing. While high-tech sectors like lithium-ion batteries and semiconductors have seen profit growth, these gains are nowhere near enough to offset the broader downturn in industrial activity.

Beijing’s response to these challenges has been both cautious and incremental. While the PBoC has cut interest rates and injected liquidity into the market, it has stopped short of the kind of bold, sweeping reforms that many believe are necessary to address the underlying issues. In contrast to the 2008 global financial crisis, when China unleashed a massive stimulus package, Beijing’s approach this time around has been much more restrained. Part of the reason for this is political. President Xi Jinping has made it clear that he wants to avoid adding to China’s already substantial debt burden, particularly in the property sector. But the longer Beijing waits to act decisively, the harder it will be to turn the ship around.

One of the most troubling aspects of China’s current economic situation is the growing divergence between what Beijing says and what is actually happening on the ground. Officially, China’s banks are reporting non-performing loan ratios that are well within acceptable limits. But behind the scenes, the reality is much bleaker. Many banks, particularly smaller regional institutions, are grappling with rising levels of bad debt, particularly in sectors like real estate, hospitality, and retail. And while Beijing has made some moves to address these problems—such as encouraging mergers among smaller banks and reducing mortgage rates—these efforts have so far been insufficient to stem the tide.

Looking ahead, it’s clear that China is facing a series of difficult choices. On the one hand, Beijing can continue to take a cautious approach, rolling out incremental measures aimed at stabilizing the economy. This approach may avoid a full-blown crisis in the short term, but it does little to address the deeper structural issues that have been building for years. On the other hand, China could take more aggressive action, such as implementing bold fiscal reforms, tackling its overleveraged property sector head-on, and allowing more market-driven forces to play a role in its economy. However, such an approach would carry its own risks, particularly in a political system where maintaining stability is often prioritized over economic efficiency. China’s growth prospects are further complicated by external factors, including slowing global demand for its exports and rising geopolitical tensions. China’s export sector, which has been a major driver of growth for decades, is now facing headwinds from weakening global demand and trade tensions with the United States and Europe. In the second quarter of 2024, China’s GDP growth slowed to 4.7% year-over-year, down from 5.3% in the first quarter. While this is still a respectable growth rate by global standards, it’s far below what China has grown accustomed to in recent years. The reality is, the days of double-digit growth are long gone, and China must now navigate a much more challenging economic environment.

Beijing’s strategy moving forward will likely involve a multiple pronged strategy. It will need to continue supporting key sectors like exports and high-tech manufacturing, while also managing the fallout from the property market collapse. On the other hand, it will need to carefully monitor its financial system, particularly the risks posed by rising bad debts and the growing burden of local government debt. Ultimately, the success or failure of China’s economic policies will depend on Beijing’s ability to strike this balance while maintaining social and political stability. Whether Beijing can navigate these challenges without triggering a broader financial crisis remains to be seen.