U.S. oil production has long been a topic of intense debate. We’ve heard the bullish calls—some even expecting U.S. production to continue growing for years to come. And yet, the reality on the ground is more complex. As we sit today, the data suggests U.S. oil production is near its peak, but the story is far from straightforward. According to James Davis at FGE, production is expected to max out at around 14-14.2 million barrels per day. We aren’t there yet. In fact, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts U.S. production to average 13.25 million barrels per day in 2024, with a slight bump to 13.67 million barrels per day in 2025.

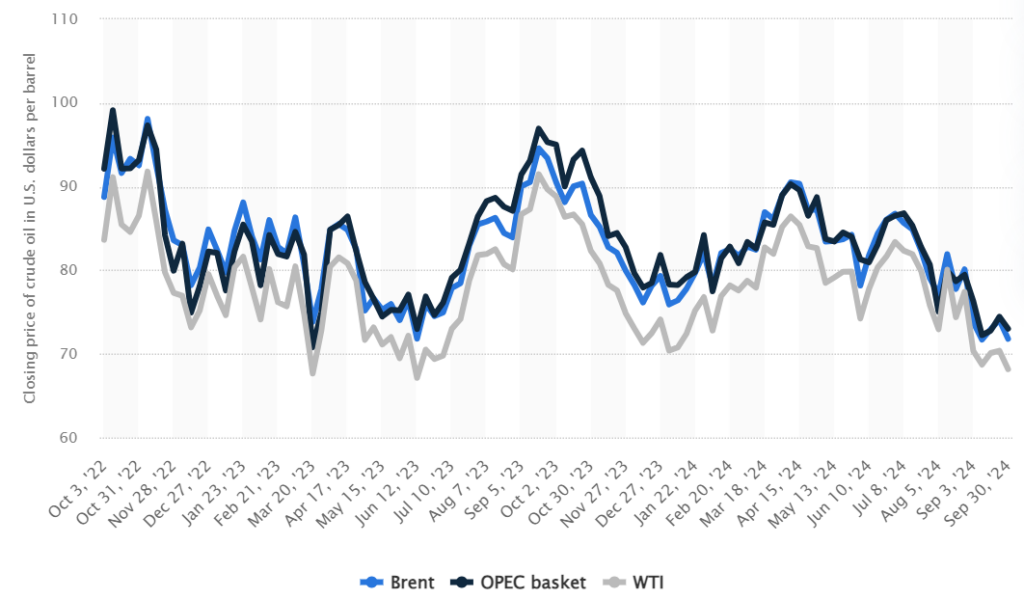

Now, these are big numbers, but let’s not forget: 2023 only saw an average of 12.93 million barrels per day, despite several bullish runs. The monthly figures for December 2023 were the highest ever at 13.308 million barrels per day, but we’re not exactly seeing that sustained. A lot of this boils down to price. Sure, the spike in 2022 pushed producers to ramp up, but the world looks a lot different now. As of September 2024, oil futures were hovering around $69 per barrel (they increased after the recent tensions but that is, I believe, a temporary geopolitical risk-premium). That’s a far cry from the post-Ukraine invasion highs of $124 per barrel in mid-2022. When prices are down, so too is the incentive to produce.

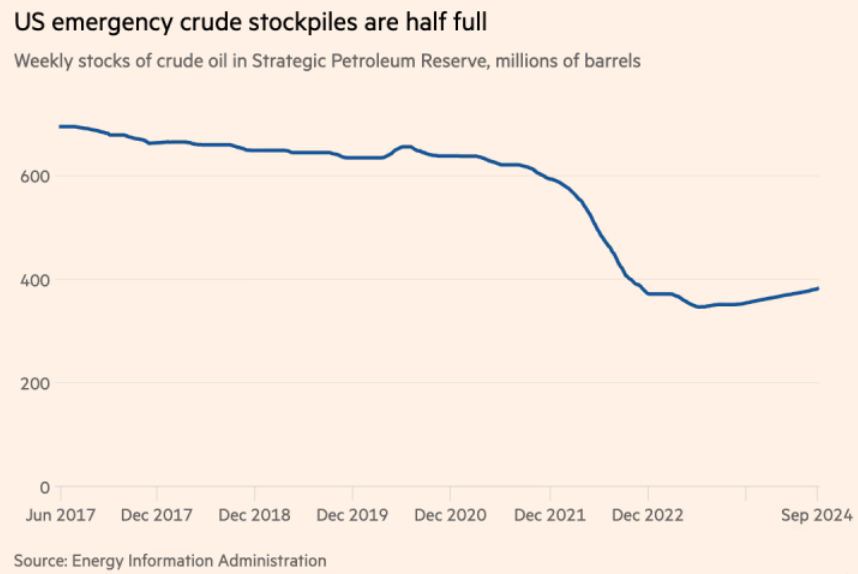

And here’s where it gets even more interesting. Harold Hamm, the shale pioneer himself, has been extremely vocal about the position the U.S. finds itself in. According to Hamm, the draining of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) has left the U.S. exposed to external shocks—especially any that might stem from instability in the Middle East. His view? The U.S. isn’t in as strong of a position as some might like to think. The SPR sits at 382 million barrels right now, which may sound like a lot, but it’s really only enough to cover about 19 days of consumption. If something happens in a critical area like the Strait of Hormuz, where 20% of global oil passes, the U.S. could be in a very tough spot.

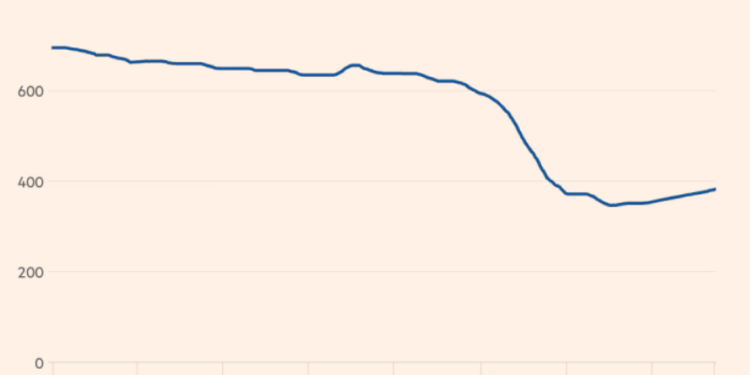

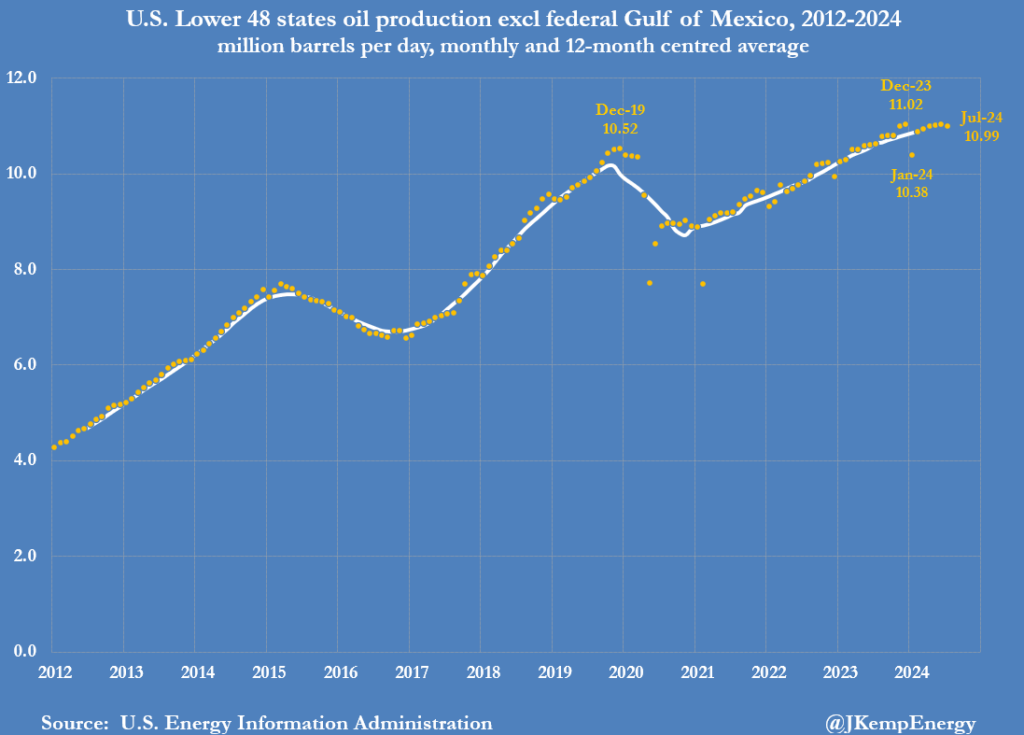

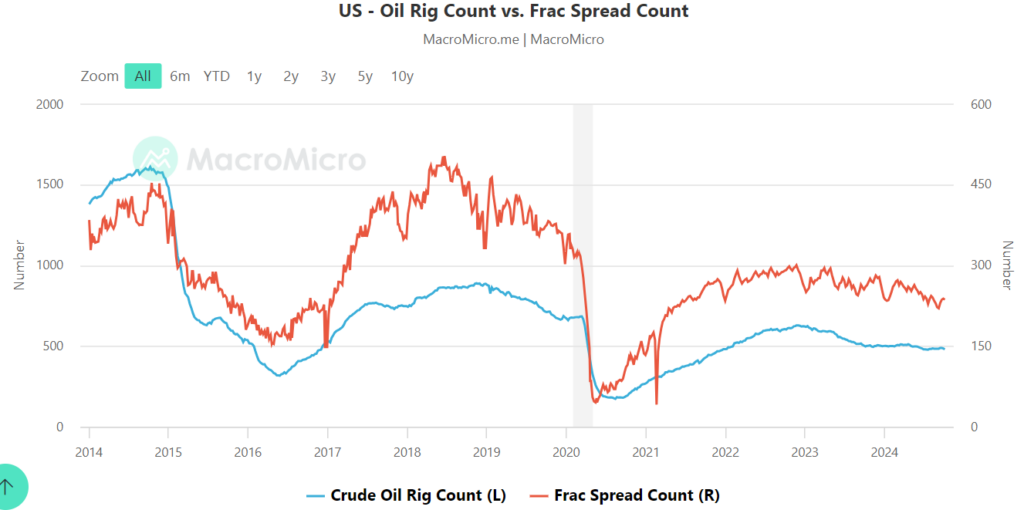

Shale sector has hit some real headwinds as well. While 2023 saw solid growth, the rate of expansion is slowing down. Crude output from the Lower 48 states—excluding the Gulf of Mexico—was up just 0.4 million barrels per day year-on-year in July 2024. That’s a steep drop compared to the previous year’s growth rates. And the reality is, if prices stays depressed after the geopolitical risk premium has been discounted in, that growth may flatline by 2025. Primary Vision’s Frac Spread Count is currently at 236 which has been reduced by 24 as compared to last year. This further shows a normalization in drilling activity in the U.S. shale sector.

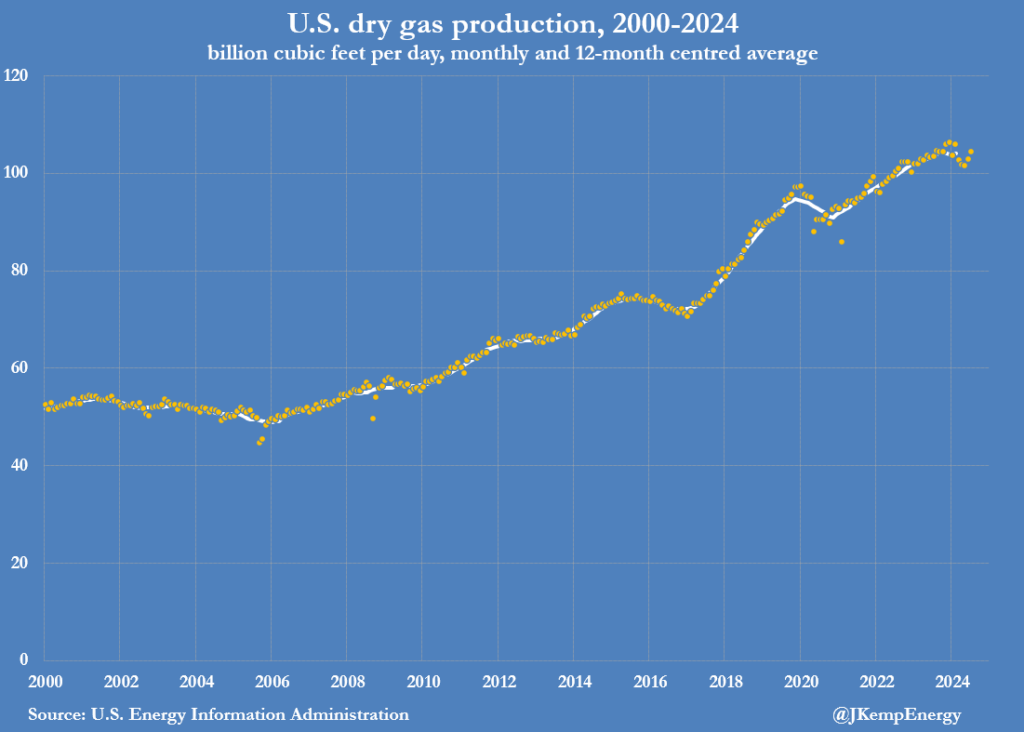

Gas production isn’t looking much better. Between February and April 2024, gas prices hit their lowest levels in three decades. That’s driven many producers to dial back drilling, and as of now, fewer than 100 rigs are actively drilling for gas. That’s down from 160 rigs just two years ago. The shale gas boom, once hailed as the answer to U.S. energy security, has been hit hard by overproduction and mild weather, which left inventories bloated.

So where does that leave us? The production boom that helped push the U.S. to record highs is slowing. The margins just aren’t there at current prices, and without a major price rally, it’s unlikely we’ll see U.S. output rise much further. But this doesn’t mean we’re heading into a crisis. While the SPR is at concerning levels, commercial inventories are up 25% over the past decade. This gives the U.S. some breathing room, but it’s still a situation worth watching closely.

The industry has matured, and while it will remain a critical part of the global oil supply picture, it’s unlikely to be the same growth engine it was in the 2010s. This slowing growth could have far-reaching implications—not just for the U.S., but for the global market. As U.S. producers dial back, we may see OPEC+ regain some of the control it lost over the past decade. In any case, the dynamics in oil markets are shifting, and anyone betting on a return to pre-2020 production growth might be in for a surprise. The landscape is more complex, and frankly, more fragile than many would like to admit.