The U.S. labor market appears stable on the surface as of mid-2025, with headline numbers that suggest continued resilience. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a gain of 147,000 jobs in June and a modest decline in the unemployment rate to 4.1 percent. Everyone seems to be happy about it. But if we dig deeper things aren’t as rosy as they look. In this article, I try to decode the numbers and what they actually mean.

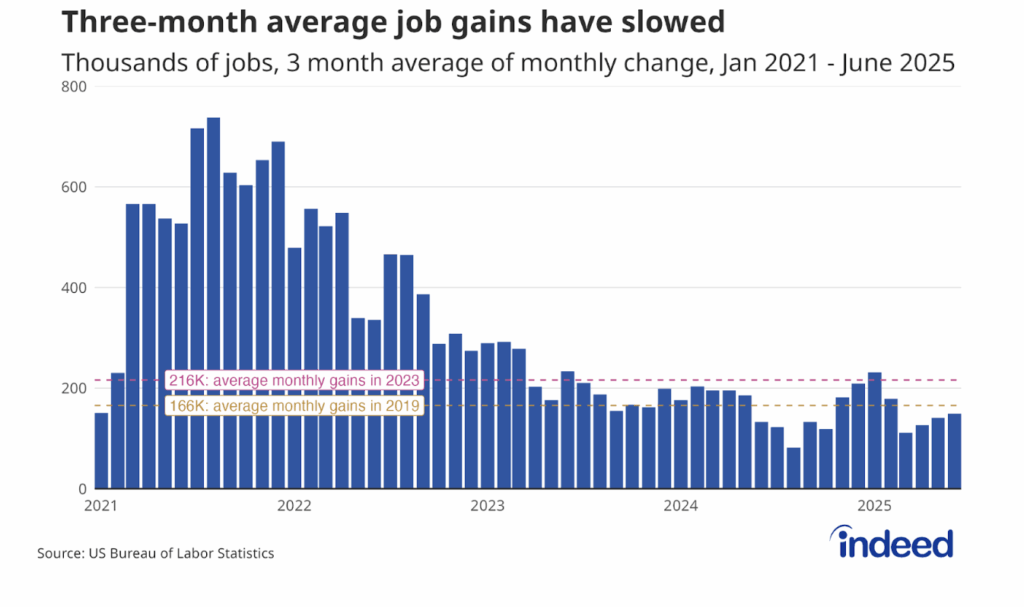

Let’s look at the averages. The three-month moving average for job creation stands at 150,000, which is slightly below the pre-pandemic norm of approximately 166,000 per month. Wage growth remains positive, averaging around 4.25 percent annually. On its face, this data implies that the labor market is functioning well and absorbing existing economic pressures. However, a more detailed examination of underlying dynamics reveals a structure that is far more vulnerable than the topline indicators suggest.

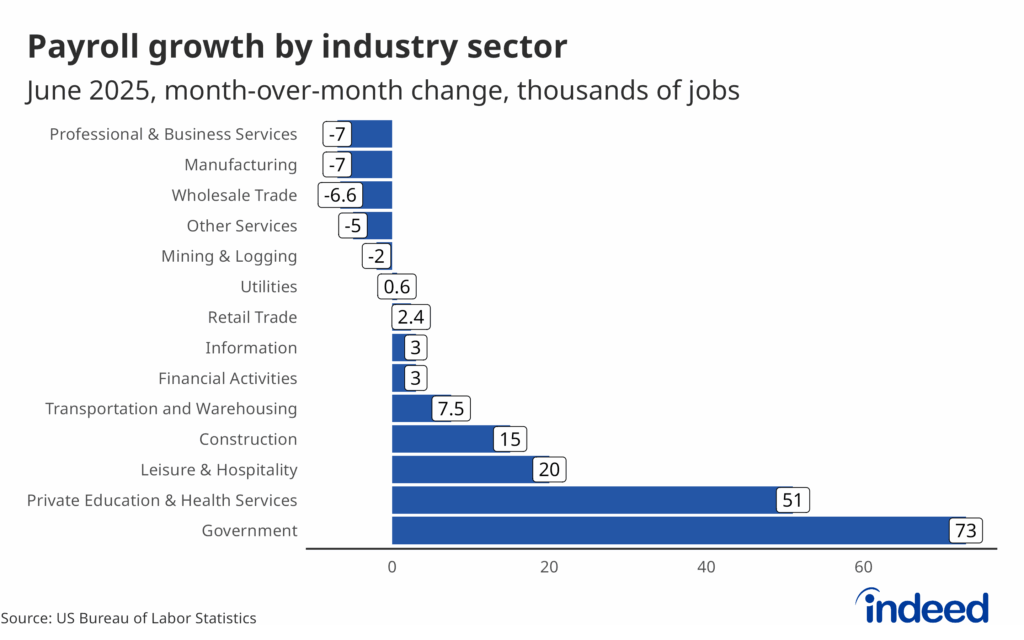

The current pattern of job gains is heavily concentrated. Nearly 94 percent of June’s net employment growth came from just two sectors: healthcare and social assistance, and state and local government, especially public education. These gains reflect continued demand in essential services, but they also mask broad stagnation across most private sector industries. According to ADP data, private sector employment actually declined by 33,000 in June, driven largely by service sector job losses. This bifurcation is critical, as it suggests that most of the labor market is either treading water or deteriorating, despite government-supported segments continuing to expand.

Further complicating the outlook is the growing duration of unemployment. The average length of unemployment rose to 23 weeks in June, up from 21.8 weeks the previous month. Although the overall unemployment rate has remained in a narrow band between 4.0 and 4.2 percent over the past year, the increasing difficulty workers face in finding new employment points to a labor market that is less dynamic and more prone to persistent dislocation. Labor force participation among prime-age workers ticked up slightly to 83.5 percent, but it remains below its recent peak in September 2024. This lack of consistent improvement suggests that the pool of available and engaged workers is not expanding meaningfully, even in the presence of job openings.

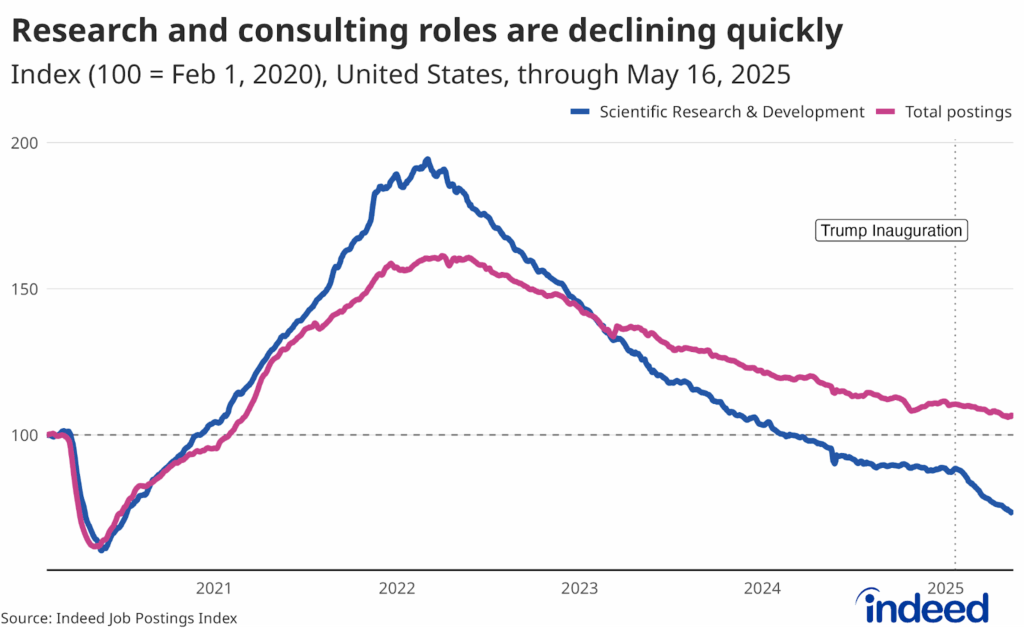

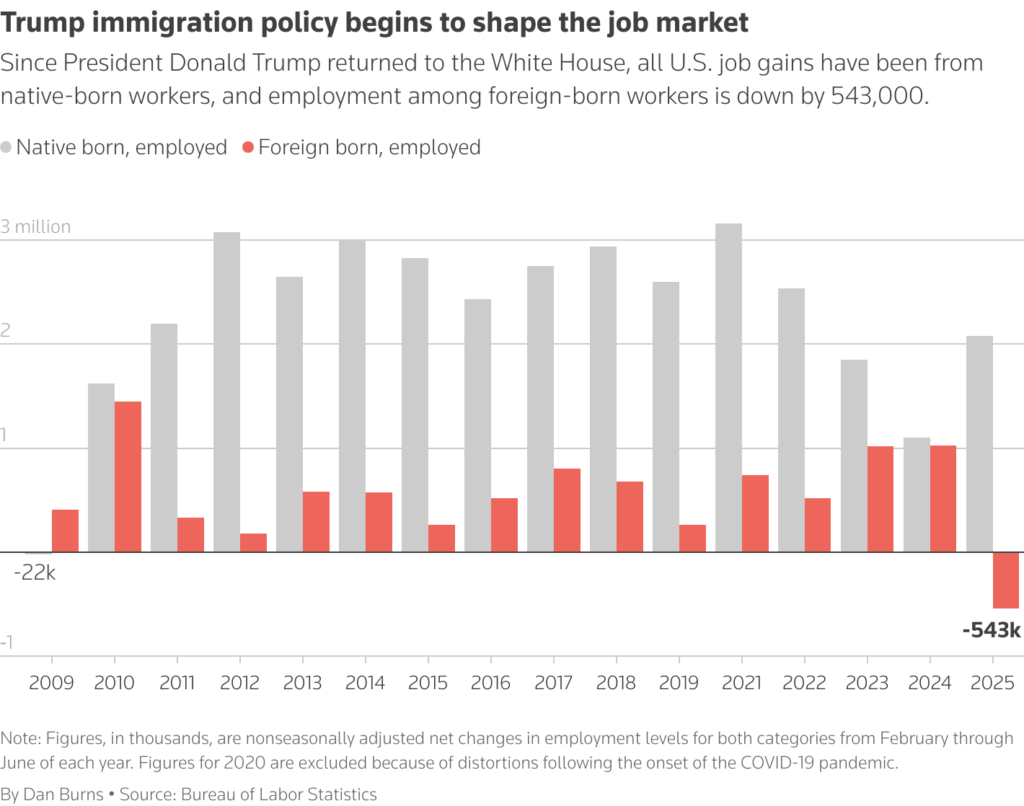

The policy environment is adding further complexity. President Trump’s trade and immigration strategies are beginning to affect both labor supply and employer behavior. Multiple economic forecasts, including from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, anticipate a slowdown in job growth during the second half of 2025. Pantheon Macroeconomics expects the monthly average to fall to just 75,000 jobs, a level that would reflect weak demand for labor by historical standards. Others, including J.P. Morgan, warn of potential negative payroll prints in coming months, even if a full employment contraction on a quarterly basis remains unlikely. A significant risk is that reduced immigration, already visible in a declining foreign-born workforce over the past three months, may impair employers’ ability to fill vacancies, particularly in sectors such as agriculture, construction, and hospitality.

Some argue that immigration restrictions will incentivize greater participation by native-born workers. However, that view remains unproven. The unemployment rate for workers aged 20 to 24 remains above 8 percent, and more than 14 percent of working-age teenagers are unemployed. While there may be slack in some demographic groups, it is not clear that policy changes alone can bring these workers into the labor force at the scale or speed needed to offset declining immigration. Moreover, the Congressional Budget Office and other nonpartisan institutions have long projected that population aging and slower natural growth will constrain the future supply of labor. Any reduction in migration, voluntary or otherwise, only compounds the demographic drag already baked into the medium-term outlook.

There is no indication yet of an imminent collapse in labor market conditions. Employers continue to show caution when it comes to layoffs, and there is evidence that firms are paying more to retain the workers they already have. That said, job growth is becoming more fragile, more narrowly distributed, and increasingly reliant on public sector expansion and labor supply constraints to sustain its current trajectory. In such an environment, even moderate cyclical headwinds could be enough to tip employment into contraction territory, especially if business sentiment weakens further under policy uncertainty.

The key challenge now is not simply whether the labor market can maintain modest monthly gains, but whether it can do so in a balanced and broad-based way. A labor market that grows only in a handful of sectors while the rest stagnates is not one that offers long-term economic stability. Policymakers and analysts should be cautious about over-interpreting stable headline indicators in isolation. The deeper trends in participation, sectoral concentration, private sector weakness, and policy-induced labor supply disruptions suggest that the economy is in a more precarious position than recent job reports imply.