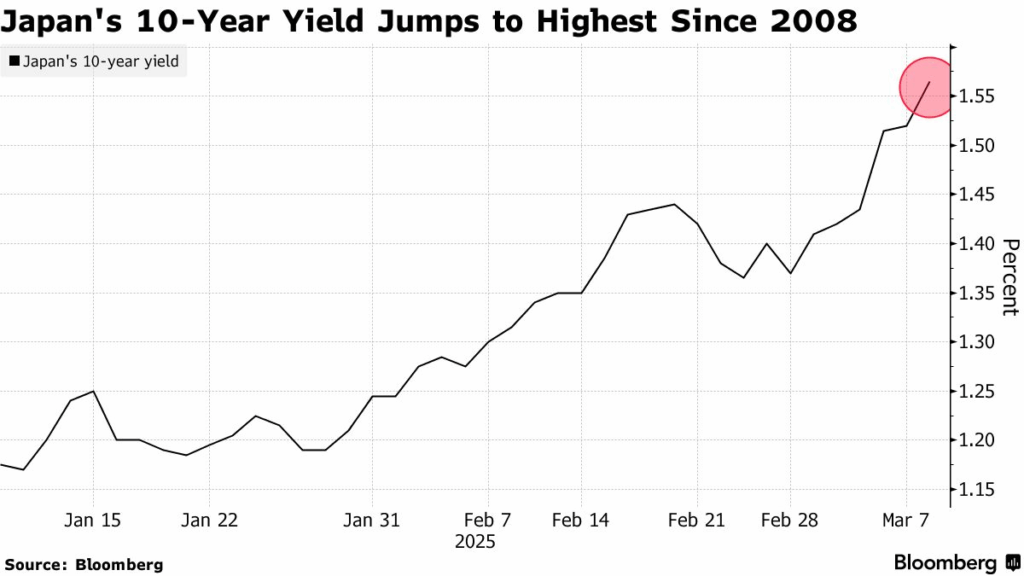

Japanese government bond yields are surging, and this week saw the 10‑year JGB jump to approximately 1.59 %, the highest since the 2008 financial crisis, while the 20‑year yield soared to around 2.65% and the 30‑year topped 3.21 %, marking recent highs across the curve. This dramatic shift reflects a convergence of intense fiscal and political tension, exacerbated by the ruling LDP-Komeito coalition’s defeat in the July 20 upper‑house election. Although the populist Sanseito party did not win a majority, its sharp rise — gaining 14 seats — highlighted growing voter support for fiscally expansive platforms. Markets are now digesting the uncertainty around fiscal policy and government stability.

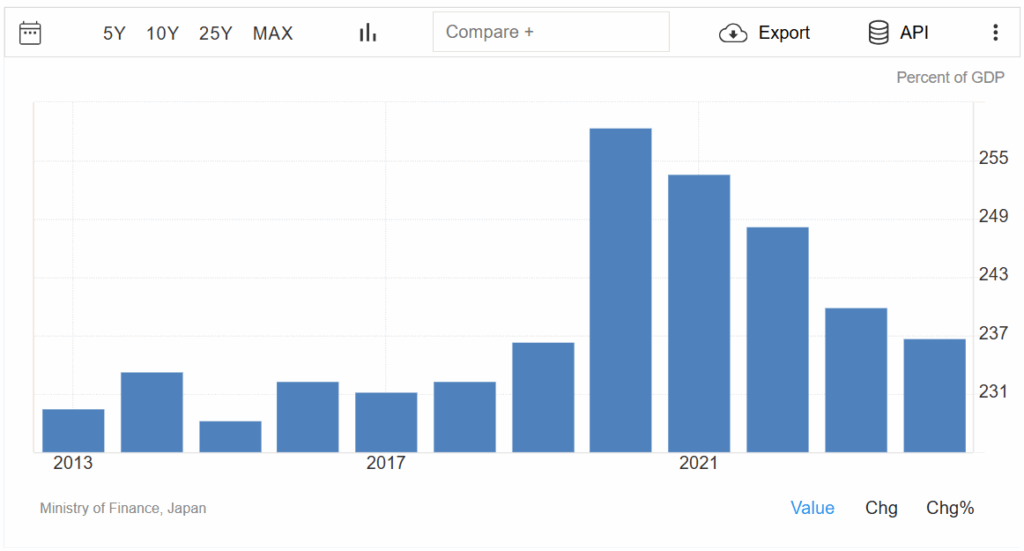

Japan’s debt exceeds 230 % of GDP—the highest among developed nations—and market confidence is fragile. Investors fear that tax cuts or cash handouts, possibly totaling over ¥10 trillion if the opposition gains ground, would deepen fiscal shortfalls and prompt further JGB issuance. That concern is already reverberating down the yield curve: long‐dated bonds are most sensitive to fiscal stress, prompting 30‑year yields to hit all‑time highs above 3.20 %.

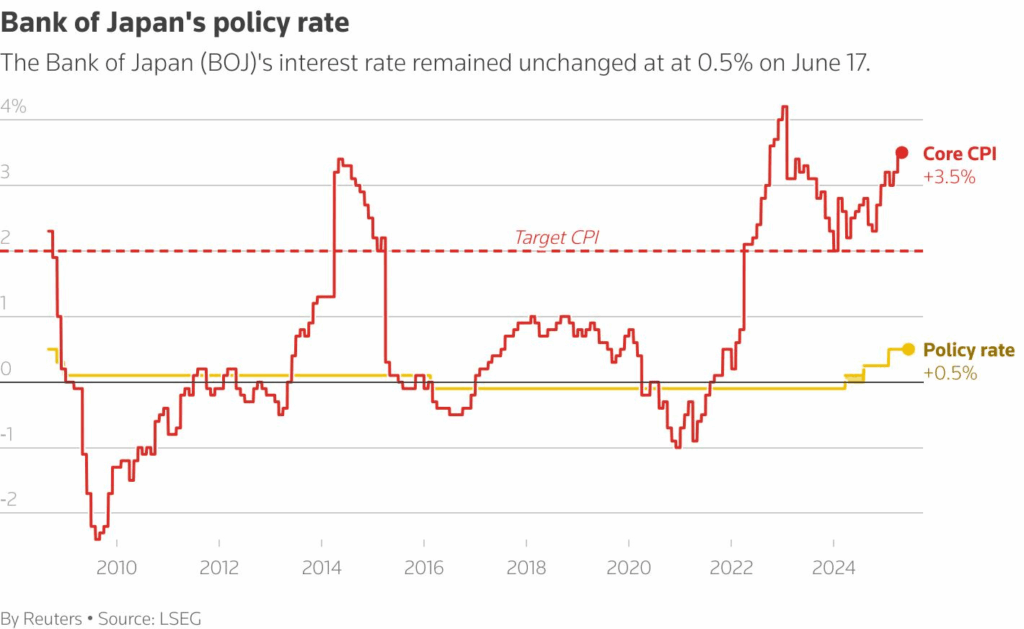

Coinciding with this, the Bank of Japan has cut back its bond‑buying pace, halving its monthly JGB purchases and slowing tapering to ¥200 billion per quarter starting April 2026. While designed to reduce its balance sheet gradually, this withdrawal of central bank support leaves yields free to respond sharply to market pressures. The uncertainty stirred by both fiscal and political developments has prompted institutions like pension funds and insurers to shift out of super‑long maturities, increasing volatility.

The surge in yields is shaking the carry‑trade foundations. For years, investors borrowed yen at ultra‑low rates and invested in foreign assets with higher yields. As JGB yields climb—especially across the long end—the cost of yen funding rises, shrinking the profitability of this trade. Furthermore, rising Japanese yields will likely lure capital back to domestic markets, pressuring global bond markets and strengthening the yen—a reversal of carry trade dynamics. Indeed, the yen has already weakened toward ¥150 per USD but could rebound as capital repatriates or carry unwinds. That said, the Bank of Japan may still tread carefully. Election‑induced fiscal expansion could constrain its ability to raise interest rates, as increasing policy rates amid volatility might further unsettle bond markets. Some voices suggest the BoJ might delay hikes until tariff uncertainty with the U.S. resolves.

Looking forward, market participants should expect continued volatility. The BoJ’s next moves, possibly a rate hike around October, will depend heavily on political stability and trade negotiations, including U.S. tariff discussions led by Treasury Secretary Bessent. Into the medium term, carry trades need to recalibrate: yen funding is no longer cheap and the risk of abrupt repatriation looms. For global bond markets, reduced Japanese demand may feed upward pressure on U.S. Treasuries and European sovereign yields. And domestically, Japan’s aging debt burden and structural challenges—such as demographics and energy reliance—demand more than short‑term populism to restore confidence.

Where this leads is still unclear. Much will depend on how fiscal ambitions translate into actual policy, how the BoJ navigates conflicting pressures, and whether external risks like U.S. tariffs escalate. What’s certain is that Japan’s yield curve is no longer insulated—market forces are asserting themselves, and investors will need to stay alert as a long-dormant dynamic begins to stir.