By Mark Rossano

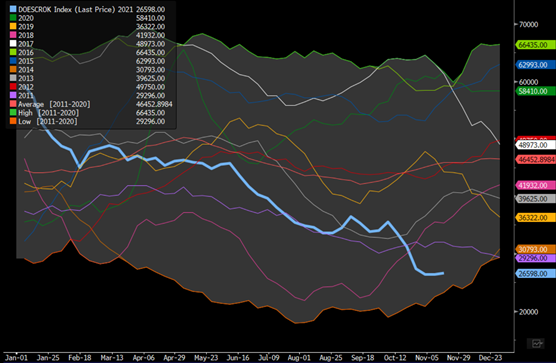

The energy markets remain as volatile as ever given the “tape bombs” or “headline risk” that continues to fly across the screens. Biden has been out threatening an SPR release and a coordinated effort with other countries. We don’t believe there will be an actual release, but if there is- the impacts will be short lived at best. An SPR release can technically only be done at a maximum of 30M barrels at a time, but they can be staggered back-to-back. We have neem saying that an SPR release would be meaningless, but it has been enough to get the attention of algos that play in the front month. The rumor mill was churning that after a small build in Cushing- there was a quick dump in futures as machines looked to “front run” the roll and the rise in Cushing. Again- this is pure speculation on the price action as Cushing did what we had described of a flattening of draws. We thought there would be a small drop, but instead we got a slight build. There will start to be a steady increase of crude left in Cushing as we approach December when PADD3 refiners look to manage storage more for the liquids tax. The shift in flows can start any time from end of Nov to 2nd week of December depending on the strength of the market and/or positioning of storage.

Storage at Cushing

We expect the pace to accelerate higher

Exports from the GoM remain a problem as prices are still elevated against the global market, but with the current fall- the WTI-Dubai spread is still $4.34. The PADD3 guys will still try to push more into the market, and we have seen a step up in exports to Europe.

PADD 3 Crude Storage

Europe’s crude imports from the U.S. Gulf are set to rise to a five-month high in November.

• 23 tankers carrying about 15m bbl of oil have arrived in Europe so far this month after loading crude from terminals in the U.S. Gulf, according to tanker-tracking data compiled by Bloomberg, port agents and fixture reports

• Another 27 tankers, hauling 18.8m bbl, are expected to arrive by the end of November

• Total volume for November is expected to be at 33.8m bbl, or 1.13m b/d, the highest since June, compared with a revised 1.05m b/d in October

Refiners will look to manage total storage by marrying exports with imports as they look to increase underlying throughput. Nominations on the Colonial Pipeline were being “given” away, but now they are making a come back as refiners compete to get product into PADD1 and PADD2. The East Coast (PADD1) is an area with broad shortfalls in gasoline/distillate, which is why there is a huge amount of opportunity for PADD3 refiners to increase runs and push more product north. But, they need to manage the slate of runs which will be a pick-up in imports (heavier crudes) while exporting some of the additional light-sweet. Colonial pipeline is looking to extend their volume incentives program, which will be good for keeping flows moving north and filling some of this spare capacity needed. The European arb is weighing on flows that has kept new exports coming across the Atlantic capped.

European gasoline exports to the Americas remain subdued in November even as major outlet like New York grapples with a fuel supply crunch.

• Weekly exports of European fuels to the U.S., mostly gasoline and blending components, were about 296k tons in the week-ended Nov. 6 and Nov. 13, compares to an average of 395k tons in October

• Total European fuel exports to the Americas are expected to be about 1.91m tons so far this month

• That includes 32 tankers that have sailed so far with 1.24m tons and an additional 16 tankers provisionally booked to load 668k tons in the coming days; more cargoes are likely to emerge for the month

• Comparatively, 38 tankers had sailed with 1.36m tons in the first 16 days in October; total tally for the month grew to 2.91m tons aboard 77 tankers

• Click here for a PDF showing the tankers en route and expected cargoes, along with historic charts

• Total volumes for the month also include about 351k tons diesel-type cargoes expected on the route so far, vs about 726k tons in the whole of October

As we head into Thanksgiving week, we expect to see demand move higher along seasonal lines, but just slightly below normal. The below shows the breakdown of TSA and how we will see a nice jump based on 2019 numbers.

The driving data will be a bit more mixed with GasBuddy showing a bigger decline vs what AAA is projecting. We believe the movements will be much closer to AAA numbers: The Auto Club Group predicts 53.4 million Americans will travel for the Thanksgiving holiday, up 13% from 2020.

This brings travel volumes within 5% of pre-pandemic levels for the 2019 holiday. GasBuddy has the following:

Holistically, the data is trending just below the trend we have seen from 2017-2019. We think we see the average at around 14.9M barrels a day of demand vs historics.

COVID is making a little run in Europe and China that is impacting driving and flight demand, which we think will continue as cooler weather comes through. Austria has reinstituted lockdowns, but we think they will be regionally based for most and not national levels. There have already been regional restrictions instituted in China and Germany, which I think will be more the norm vs a broad lockdown. But, it will impact economic activity and underlying demand as consumers try to avoid exposures in general and shift some spending habits. It will also be a big impact on inflationary pressures as we show in the next segment looking at underlying costs. The European data will keep trending lower while China stabilizes at these levels.

U.S. activity is slowing down a bit, but still remains closer to normal- which is a positive sign heading into year end:

Airline activity will be the biggest overhang as flight schedules are reduced well above seasonal norms as restrictions are implemented. This is something we believe persists into next year as countries keep areas open, but limit broader movements by air travel. Globally, the passenger flight schedule for the 11 weeks ahead has declined by less than 0.5% week-on-week. This follows a significant drop last week.

In Europe, departures in the Eurocontrol area fell by 3.5% weekon-week. Spain and Germany registered large declines in flight departures. ● In the U.S., passenger numbers increased by 2.5% as the country reopened to foreign international tourists. Passenger throughput levels are approaching levels seen in 2019. ● In Asia Pacific, departures cratered in China again, for the second consecutive week. Flight activity in Australia, India and South Korea increased as countries in the region continued to reopen slowly.

China | According to Airportia data, the number of flights kept dropping sharply below 2020 levels (down almost 50% YoY). It confirms that new restrictions, linked to #Covid_19 resurgence, have already affected the economy.

Global storage levels have also rebounded from some lows as demand declines, and more products hit the water looking for the highest bidder. We have been discussing a broad increase in flows and another data point has emerged bringing Middle East product into Europe and generally speaking the Atlantic Basin.

Shipments of refined products to Europe from the Middle East — mostly diesel and jet fuel — are set to surge this month, just as Covid-related lockdown concerns are starting to rise again on the continent.

• 18 tankers hauling about 1.16m tons of Mideast fuels have arrived in Europe so far in November

o An additional 16 vessels, or 1.1m tons, are en route and expected to arrive before the end of the month; this includes 774k tons sailing toward transit points and yet to signal a European port

o NOTE: Some tankers signal Suez Canal or Gibraltar as a transit point and may later sail on to other regions

o Compares with 25 tankers that arrived with 1.82m tons in October

• Shipments from Yanbu are set to more than double m/m to about 444k tons, after a multi-month low in October

• For December, 14 tankers have been provisionally booked to load 1.04m tons so far; another 3 tankers are underway with 220k tons

OPEC+, EIA, and IEA are now showing builds in 2022 that we have been talking about since June. The physical market has been indictive of slack in the market as China has chosen to release crude from internal storage instead of buying in the open market. They have taken normal term cargoes but have left all spot on the water. China has left the import quota flat year over year while increasing a tax probe into independent refiners, which has dragged down some ESPO premiums as teapots slow purchasing. Chinese imports of crude was at 39 month lows, and while we expect a bounce in Nov- it will still be lackluster.

The physical market (especially crudes that normal go into the Chinese markets) still remain broadly available in the market. In my career, I have never seen so many Angolan cargoes available in the loading month.

WAF UNSOLD CARGOES:

• NIGERIA: 15-20 cargoes unsold for December loading

o That’s a slower pace than normal given January trading is underway; Still, the overhang is smaller than about a month ago when 25m bbl of crude was unsold, mostly for November loading

• ANGOLA: 4-7 unsold December shipments, a somewhat slower pace of sales than a typical month

o Drops from 7-8 unsold cargoes for November around a month ago

• DJENO: 1-3 consignments unsold for December

o Drops from 3-4 unsold for November a month ago

There remains a significant amount of slack in West Africa that keeps floating storage at near record highs as discounts will accelerate in order to clear Nov. Angola has already posted Jan, so they will be driven to clear Nov as Nigeria has already deferred some cargoes in Dec. The below chart shows how WAF cargoes are sitting at 2021 highs and seasonally adjusted- the highest of all time.

The middle east will be an important place to watch as more cargoes come to market and floating storage is already trending slightly above average. They are still in a very normal range, but the trend is starting to shift higher a bit. This will be a much broader signal for softness in the market if these cargoes start to show up in storage.

We expect headwinds to persist in the physical market, while the paper market fluctuates based on some macro events including the US Dollar. As inflation fears increase at Emerging Markets, they will be forced to raise rates and purchase USD to help stabilize local markets, which will keep the USD supported at these elevated levels. So the paper market should find some buyers around here as investors were waiting to increase holdings, but remain fairly capped as the dollar and physical markets weigh on total movements.

Before I go into the broader inflation and retail sales story: Prices received vs prices paid is a massive lag and depending on inventory cost and what prices paid looks like going forward you will get a broad deviation on “how fast” prices are passed on to the consumer, and the cost of raising prices is extreme for some companies which is why the Fed as “Flexible CPI” and “Sticky CPI.” I can have a conversation about inflation from an academic standpoint through monetary policy and liquidity, but those are talks left best for academia. As costs rise- businesses will have to push through whatever price increases they can to help maintain normal business operations. We can dissect the “phenomena” of inflation and monetary policy utilizing Milton Friedman and other economists, but cost increases remain the biggest driver of pricing in today’s market- and there is NO sign of it abating. We expect it to give way to stagflation over time, but that is more a 2H’22 event vs 2021. For example, if a company is seeing all 10 of their input costs going up 3%-5% a month- will they raise or keep prices the same? For some companies, it is very costly- which is why I go through the different of “flexible” vs “sticky” inflation in the below segment because it is more costly for some companies to raise prices vs others- so we have to take all of this into account.

Quick update on food:

All sections of grocery stores are seeing rising food prices, National Grocers Association President and CEO Gregory Ferrara says on Bloomberg Television Friday.

• When costs are rising across the supply chain for food, grocers “can’t absorb everything,” Ferrara says

• Much of food inflation is being driven by labor shortage, especially a shortage of truck drivers

Trucking isn’t getting any better as long haul flows still remain well off normal, and the demand rises across the board- as we discussed last week.

October retail sales came in stronger than estimates and right inline with our thinking that spending has been pulled forward. The data has been showing that customers are worried about price increase and supply chains, which accelerated their purchases “ahead” of normal holiday spending. The biggest question will be how Nov progresses- because it will be a good test on how much activity was moved forward to Oct and if inflationary pressures are starting to curb buying. Retail sales are always reported in nominal terms, but even when we factor in inflation- retail sales remain elevated across the board.

Even when we normalize inflation, retail sales remain well above pre-COVID levels- down year/year but still hanging in strong even though underlying consumer data worsens. The Consumer Reports and Michigan surveys all point to concerns and reduced spending, but their actions are something very different as spending remains robust. Real retail sales increased at 6.7% annualizes pace through Oct, which is flat over the last 4 months but still above the pre-COVID average of 2.5%. The spread below is the interesting backdrop between what people say vs what people do. There was a lot of spending pulled forward into Oct, and as prices continue to increase- pressure will only grow on spending. “Target warned that cost pressures are creeping up, stoking anxiety among investors that inflation will weigh on profits at big retailers. Walmart Inc. Chief Executive Officer Doug McMillon said Tuesday that the company’s costs are rising more quickly than its prices.” The bigger companies are now struggling to pass through prices fast enough to cover costs, which will show up in profit margins as we go forward.

Savings have continued to fall as real wages decline and the additional spending is financed with savings and credit.

Credit has seen a strong bounce, and all the recent data suggests more people are buying goods with credit or buy now/pay later structures. This is increasing the revolving credit in use, which is still below pre-COVID levels but growing steadily as savings are dwindled and real wages don’t keep pace with inflation. Revolving credit usage is still nearly 8% below its pre-pandemic peak, so there is room for it to expand further to fund consumption. This is a key reason why it is so hard to nail down when the consumer is “tapped out” because Americans utilize credit more than most places around the world. We are a culture built on consumption, and the view that we need it “now.”

For example, consumers are answering surveys highlighting the concern people have over pricing, inflation, and future financial conditions. But, even with these concerns- spending still remains elevated.

The global economy is facing a broader issue when we look at leading indicators and what that will do for ISM manufacturing data around the world. Locally speaking- the U.S. data remains supported with some better leading data out of US Empire State Manufacturing and Philadelphia Fed Business. Some of the other indicators have been either right in line with expectations or just slight misses. The internals still show a fairly mixed bag with employment being fairly strong, but delays and pricing are still huge upward drives showing the stickiness with the underlying inflationary pressures still front and center.

The only thing we can do is look at leading indicators and how wages are managing with the upward pressure in living expenses. The problem is the relationship between prices and wages because they become circular creating a feedback loop. As living expenses rise as prices for goods rise, companies raise wages to keep pace with the increase in prices, but as wages increase- companies have to raise prices to cover the rising costs. The only way to get out of this never-ending cycle is to raise rates, and essentially slow the economy. We have seen consumers “balking” at prices, but so far it hasn’t resulted in a reduction in spending. One of the big reasons we haven’t seen a decline (yet) is the availability of replacement goods or substitutes. Consumers are expecting prices to increase, so the sticker shock is minimized to a point because everyone is going into the store with the view prices will be elevated. People are also still holding out hope that prices will normalize, which is true to a point as the supply chain catches up and some of the insane prices on shipping/logistics abate. But, companies are currently predicting more price increase because as supply chain costs are reduced- it will be quickly replaced by rising wage costs.

The below chart helps to depict the shift in “lower-cost alternatives”, which can help bridge near term demand as below trade down. The focus on deals/ discounts is logical, but as companies struggle with costs- they are less willing to offer broad discounts. They will use marketing ploys, but typically the net benefit to the consumer is reduced. For example, instead of getting 20% off the total- it turns into 20% off one item, or something being 30% off instead of 40% off. Another big one- instead of Buy One Get One Free- it shifts into Buy One Get One Half Off. The consumer can still believe they are getting some sort of discount, but when we compare it to previous years- the savings are actually reduced.

As more people move down to the lower-cost alternative, shortages increase and drive-up prices for the “cheaper” product as supply chains limit availabilities. Another important point is the shift in unit price or shrinkflation. Companies are reducing volumes in products while either maintaining or slightly increasing prices. This also helps hide some inflation because volume isn’t considered in the underlying CPI calculation- so it is a way to buffer some of the increases.

The shift in the calculation is a key reason we look at underlying movements across varying inflation metrics. The one that we have been highlighting most recently is the “sticky” inflation metric. The flexible inflation metrics is pulling the “sticky” side higher as the pressure grows and more cost is moved down the supply chain. As the “Flexible” calc remains elevated it will keep pulling the sticky side higher, which will provide a prolonged impact to underlying consumers. This will be driven by the increase in wages as well as housing.

Price Stickiness in the Consumer Price Index

What makes a price sticky? The answer to this question has puzzled economists since John Maynard Keynes built his General Theory around sticky prices more than 70 years ago. The prevailing belief is that, in some markets, changing prices can involve significant costs. These costs can greatly reduce the incentive of firms to change prices.

While a sticky price may not be as responsive to economic conditions as a flexible price, it may do a better job of incorporating inflation expectations. Since price setters understand that it will be costly to change prices, they will want their price decisions to account for inflation over the periods between their infrequent price changes.

While some economists wrestle with the question of what, exactly, causes prices to be sticky, others have taken on the tedious task of documenting the speed at which prices adjust. The most comprehensive investigation into how quickly prices adjust that we know of was published a few years ago by economists Mark Bils and Peter Klenow. Bils and Klenow dug through the raw data for the 350 detailed spending categories that are used to construct the CPI. They found that half of these categories changed their prices at least every 4.3 months. Some categories changed their prices much more frequently; price changes for tomatoes, for example, occurred every three weeks. And some goods, like coin-operated laundries, changed prices on average only every 6½ years or so.

Using this information, we divided the published components of the monthly CPI (45 categories derived from the raw price data) into their “sticky-price” and “flexible-price” aggregates. While it isn’t at all clear where one should draw the line between a sticky price and a flexible price, we thought the average frequency of price change found in the Bils and Klenow research was a natural separating point. If price changes for a particular CPI component occur less often, on average, than every 4.3 months, we called that component a “sticky-price” good. Goods that change prices more frequently than this we labeled “flexible-price” goods.1

There are some signs that spending is starting to slow down a bit:

Consumers still indicating strong interest in goods & services spending per Google search activity; but recent sore spots include clothing, movie theaters, and restaurants per DataArbor. There is usually a seasonal slowdown, but it normally kicks off closer to Dec with Jan being the “worst” month when considering spending activity. The below data was a leading indicator for how strong Sept/Oct were so it will be a good test for how much activity pared back in Noc.

We have been talking about the weakness in real wages, but here is a look when we go back to look at underlying mix-shift effects. There is underlying weakness when we consider the year over year, but the movements have been continuous higher when we consider the top part of the chart. “Mix-shift effects always have to be taken into account with average hourly earnings, but level of inflation-adjusted earnings (blue) still largely around pre-virus trend despite y/y growth (orange) being in negative territory.” The pressure is still in the system, but when we compare it differently there is still some earnings power that remains in the market.

The problem with the earnings power is “where” it resides. The highest earning quartile is seeing a big shift lower in wage growth while the lowest faction shifts the highest vs all other quartiles. This is pulling excess discretionary income from the system because the wealthier individuals typically spend more on goods and services. The additional money to the lowest quartile is just trying to keep pace with the rising costs as they are exposed the most to increasing food and energy prices.

While the lowest earners are seeing an increase in wages, they are also the most impacted by the rise in food and energy prices. We have been covering the food movements for some time, and as fertilizer and all underlying costs continue to push higher- it locks in higher prices in ’22 already. This will keep the pressure on the lowest quintile as more money is pushed into just general living expenses.

This chart goes a step further to look at the percentage of income spent on food vs the actual dollar value. Peril of rising food prices is that lowest-earning cohort in U.S. spends (on average) $4k on food per year, representing 27% of income … conversely, highest-earning cohort spends (on average) $12.2k on food per year, which is just 7% of income. The below chart is also from 2020, and doesn’t capture the recent run up in pricing and how that has shifted the percent of income to be spent on food. The rise in wages can bridge some of that gap, but we have seen a big spike in these key areas which will exhaust budgets and force a change in consumption and spending patterns.

The below is the average breakdown of the amount of money spent per category (I wish my healthcare was that cheap). Groceries is the second biggest expense for the average household, so the increase across the food supply chain will be the biggest drain on resources.

When we look down the supply chain, the costs are still ricing for companies as they look to pass them down again. There is still a divide between Prices Paid and Prices Received.

Even as the supply chain gets a bit better- the wages side is picking up the slack on the cost front.

When we pivot for a moment to housing, rents have shifted up again and will be a big driver of the next round of inflationary pressures.

The next stop for inflation is stagflation. Prices are going to be sticky as supply chain costs are replaced with wages and other input costs. The Producer Price Index is moving higher around the world, especially in key areas that are big trade partners with the U.S.

Even as we have container rates and shipping day rates starting to come down, the products sitting on those ships are getting more expensive. We will see elevated pricing on goods leading to stagflation as consumers slow down their purchases to avoid the higher prices.

On the wholesale/retailer level, inventories remain at record lows and have started to move lower again. The problem is companies don’t want to be sitting on high priced inventory if the consumer slows so they are trying to balance their underlying levels. If a company buys up inventory now- they will have a huge underlying cost that they will try to pass through to the consumer, but if the buyer is already balking now- it will be difficult to pass it through and protect margin and underlying profitability. On the flip side, they need a certain amount of cushion to maintain normal operations so they are still beholden buyers, but no one is looking to lock in big orders at these price levels. This is another reason new orders have slowed as companies wait for backlogged orders to clear and take delivery.

Even as prices start to normalize- companies will be in the market trying to replenish some of their inventory, which will slow the “normalizing” process because there will remain buyers. There is always a chance of a much bigger buyer strike, but it is unlikely we get a big reversal in consumer spending barring a recession.

Based on the underlying calculation- as the sales slow (the denominator)- it can help inventories grow- but that will also leave retailers with more expensive inventory that they may not move through the system. Therefore, the rebuild of stock will take time even as some parts of the supply chain normalize.

The pressure is not just in the U.S. as China also faces problems across their economy. The data recently disclosed was mixed, but when you normalize some of the data it still looks weak across the board.

Data dump – econ data

China’s stats bureau published the monthly econ data for October on Monday.

• Retail sales rose 4.9% y/y in October, up from 4.4% y/y growth in September.

• Fixed asset investment (FAI) fell 2.9% y/y in October, compared with a 2.5% y/y fall in September.

• Value-added output at industrial firms rose 3.5% y/y in October, versus 3.1% y/y growth in September.

The consensus forecast for retail sales was for 3.8% y/y growth.

Industrial value-added output was expected to increase 3.0% y/y.

However, China is not yet out of the woods.

• The recovery in retail sales was largely a result of higher prices:

• In real terms, growth slipped from 2.5% y/y growth in September to 1.9%.

• The stabilization in industrial activity reflects the easing of previous power-related supply constraints more than a recovery in demand.

• Power supply jumped 11.1% y/y last month.

The continued fall in FAI also bodes ill.

Outside of last year’s lockdown, FAI has never recorded y/y falls before.

• The drop in FAI reflects a huge drop in real estate investment, but there is no sign of Beijing stepping in to make up the difference:

• Infrastructure investment fell 4.8% y/y, the sixth month on the trot that spending has been down on the previous year.

• Get smart: The better-than-expected numbers are being used to explain why officials haven’t been doing more to support the economy.

• But a dig under the surface reveals that the economy still faces a host of problems.

Get smarter: Beijing isn’t engaging in stimulus because it thinks the worst of the slowdown is now over.

• Such restraint also highlights that strong economic growth is no longer the main priority.

The key here is in real terms retail sales only rose 1.9% compared to the real industrial output growth of 3.5%. Another overhang is the slowing across the real estate market that has weakened further in Oct with the pace of the slowdown accelerating in Nov. China is now starting to issue/ talk through more tax cuts in order to stimulate the economy or at least provide needed cash to the:

• In October China’s economy continued to rebalance towards consumption, as in recent months, but much too slowly to make up for the deep worsening of the imbalance that occurred last year. Retail sales were up in October by 4.9% compared to last year.

• They rose by an average of 4.6% a year compared to 2019. This was higher than consensus expectations, but still fairly low. During the first ten months of 2021, retail sales were up by 14.9% compared to last year and by an average of 4.0% a year compared to 2019.

• Industrial production was up in October by 3.5% compared to last year and by an average of 5.2% a year compared to 2019. This was also higher than expectations, but also still fairly low.

• During the first ten months of 2021, industrial production was up by 10.9% compared to last year and by an average of 6.3% a year compared to 2019.

• Whether you look at just at October numbers or year-to-date numbers, retail sales – a proxy for consumption – grew faster than industrial production in 2021, but growth in the former still seriously lags growth in the latter in the two years since 2019.

• Although the growth data came in above expectations, the stock market was still down today, probably because additional data suggested that property prices in China were broadly down in October. New home prices declined by 0.25%, after a 0.06% decline in September, and second-hand homes declined by more. What makes this risky is that if it doesn’t turn around soon, and leaves Chinese homebuyers convinced that the days of ever-rising prices are permanently over, it will cause a substantial deflation in future demand.

The issues in the real estate market are continuing to expand and driving down the need for industrial metals within the country.

Evergrande has slashed the amount of money they are charging for apartments in a fire sale to raise capital and complete some of these homes that remain half finished.

China’s home slump deepened in October as declines in prices, sales and property investments widened, adding pressure on authorities to stabilize the market. New-home prices in 70 cities slid 0.25% last month from September, when they fell for the first time in six years, National Bureau of Statistics figures showed Monday. Residential sales dropped 24% from a year earlier, the most since last year, striking a blow for developers during what is traditionally a busy season, Bloomberg calculations based on official data showed. At least 21 cities, mostly smaller and with weaker economies, have imposed floors on the lowest prices developers can sell to limit the market slump there, the China Business news reported Monday. Values dropped 0.37% in so-called tier-3 cities, bigger than tier-2 declines.

The issues in the real estate market has caused enough panic that the PBoC is allowing some additional lending by the companies with some new issues recently announced. But, it doesn’t change the fact that the local consumer still has MASSIVE exposure to the real estate market, and as the completion of new buildings is delayed- no one is getting paid on their investments.

The use of shadow banking remains an important function as well as the Wealth Management Products (WMPs) to finance activity.

While there’s no indication that protests over WMPs have turned violent, even small-scale demonstrations are notable in a country where public dissent is rare. In Shenzhen, hundreds of angry investors have stormed the headquarters of both Evergrande and Kaisa. Similar scenes have played out in Shenyang, near the border with North Korea.

Regulators have been tightening rules on WMPs and other parts of China’s $13 trillion shadow banking system for years. But it was only recently that they moved to cut off one of the last major sources of developer-linked investment products. Earlier this year, authorities banned local over-the-counter exchanges from issuing WMPs with real estate as the underlying assets, two people familiar with the matter said.

This is why the consumer has so much exposure to the underlying real estate market.

The consumer is getting hit from all sides as prices are now rising within the country as companies struggle to pass through rising costs. This is another key reason that the government is looking at ways to reduce the stress and new tax cuts are being considered to support local companies.

No matter what China tries to do- all parts of their economy are slowing. Some at different paces, but they are all moving in a flat or deceleration direction.

Here are some important periods to watch for maturities that could create a liquidity event:

The level of debt is massive across the country, and given the linkage of banks with “perpetual bonds” and the consumer with MVPs- these debt levels are concerning.

Even though the Chinese market has fallen- there is still more risk to the downside as some parts of the markets have yet to respond to the issues.

As the market turns to the government to protect the economy, it is interesting to see how much land sales drove local government revenue. As we look at the revenue generated by land sales to the local government, and as this cash flow stops and tax cuts are expanded- the shortfalls will only grow.

Inflationary pressures are also growing in India again after some of the base effects fall away and food prices/ vegetable oil prices start to shift higher again. We are a bit more aggressive on our views for inflation in India and believe they breach the RBI top limit by Jan of next year. There is accelerating pressures around the world, and they will show up everywhere as rising input costs. Bloomberg Economics is saying by 2Q, but based on wholesale prices and import pricing- we think that is pulled forward.

“The base effects that have contributed to lower inflation until now are set to turn less favorable in the months ahead. Our analysis of components of the CPI basket also shows the recent drop since May was largely driven by a tumble in a set of food items where price changes tend to be short lived — and they are already showing signs of turning higher since October.

• We expect inflation to escape the RBI’s 2-6% target band by the second quarter of fiscal 2023.

• The reduction of roughly 5% in gasoline prices and a 10% decline in diesel — reflecting the government’s decision in November to reverse last year’s fuel tax hikes and additional price cuts by state governments — should counter the surge in prices in October and mitigate further upside risks to inflation.”

While industrial growth fell in Sept, there will be a nice bounce in Oct and Nov, which will help support activity in the near term. Diesel sales still remain a concern, but the consumer (gasoline) demand is still strong with little adjustment in the near term, but as wholesale prices and PPI rise globally- more pain to come.