By Mark Rossano

The U.S. Release of Crude From the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR)

The “tape bombs” have been dropping for several weeks now about an SPR release and a “coordinated” effort to bring down the price of crude. There is a global effort to release crude from countries’ reserves, with the U.S. announcing 50M barrels (which is effectively 32M because 18M was already scheduled); India will release 5M barrels, the U.K a potential 1.5M, South Korea about 3.8M, with more to follow out of China and Europe. It is important to understand what the purpose of the release was: Are they trying to slow the rise of crude prices, or adjust the price of gasoline, diesel, and heating oil? Crude prices fell by about $8 prior to the announcement and bounced once the details of the SPR release became official, but the price of gasoline still remains elevated heading into one of the biggest travel days of the year. It is also important to consider: How will OPEC+ respond to the SPR release?

There are many different types of crude in the world, and each one creates a unique amount of refined products requiring a different process depending on the attributes of the oil. The cost of refining “sour” crude has been rising given the price of natural gas and hydrogen to effectively “crack” or process the oil into its different products. This has created more demand for light-sweet (higher API-viscosity and much less sulfur) as well as medium-sweet crude that simplifies the refining process by reducing sulfur from the very beginning.

Why is this important? Because the U.S. release from the SPR is 100% sour crude, which doesn’t have much demand in the world right now, ESPECIALLY in the United States. Refiners in the U.S. have been trying to manage cost by running sweeter blends. In order to make gasoline and ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD)/ ultra-low sulfur heating oil (ULSHO), a refiner can only leave 15 parts per million or less of sulfur in the stream. So the crude leaving the U.S. reserves will mostly go to the export market.

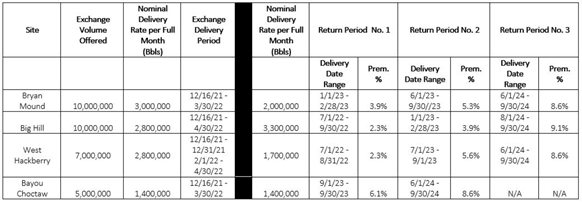

Because 18M barrels were already slated for sale per the earlier agreement passed by Congress, this means that the announcement was only 32M barrels, and is being put out on “loan” because it has to be paid back with interest. The 18M is a straight sale into the global market, but the 32M has to be “paid back” to the SPR between July ’22 and Sept ’24 depending on the location and return period listed above. Given the quality of the crude being sold, it is more likely to end up in India and China vs the U.S. based on the current slates being run.

The important thing to watch going forward is the number of bids that will come from refiners or trading houses, because no one is forcing them to take these barrels. A higher quality crude from West Africa has been struggling to find buyers highlighting some weakness in the physical crude market. By adding barrels of lower quality crude to the market, may not have the lasting impacts on price that the governments expect. The SPR may receive no nominations or less than the 32M slated over the program’s lifecycle. A refiner will have to evaluate the current price of the SPR release, as well as the cost of returning the crude in the future. In the market’s current backwardation, it may seem attractive, but the elevated cost of processing sour crude will limit total purchases. The front of the crude curve fell in anticipation of the official announcement. This “achieved” the goal of bringing down prices . . . for now. On the other hand, the cost of gasoline was already starting to slow prior to headlines talking about an SPR release.

Based on the quality of crude being released and its likely final destination, the release of SPR barrels will do little to adjust the price of gasoline and diesel/heating oil based on several factors:

1) U.S. refiners are currently consuming 15.397M barrels per day and given the sour slate, refiners will maintain import operations to achieve their current crude blend. We will see an increase in activity to about 90% utilization rate over the next few weeks as refiners exit shoulder season, but the ramp in runs will pull more crude in from the international market that is sweeter vs sour.

2) The U.S. has a location problem. PADD 1 (East Coast) is short gasoline and distillate, while the rest of the country is well situated for product. As refiners increase operations targeting heating oil, they will naturally create more gasoline, helping to close the shortfalls in some storage locations. Roughly speaking, when a refiner creates 1 gallon of diesel (heating oil) they also create 2 gallons of gasoline. This is why we normally see a big spike in gasoline storage during the winter months. The issues have expanded in the distillate world as heating oil and road diesel compete in the market. The broad supply chain problems have increased the demand for trucking and the diesel used to power the rigs. Road diesel vs Heating oil: In 2012, NY became the first state to require ultra-low sulfur heating oil (ULSHO)—heating oil to have a sulfur content of 15 parts per million or less. DE and NJ transitioned to ULSHO in ’16, and all six NE states transitioned to ULSHO on Jul 1, ’18. Between the rising demand and the destroyed Philadelphia refiner, there are shortages on the East Coast with limited ways to close that gap. The East Coast can either purchase produce on the Colonial Pipeline or purchase it from the international markets.

3) Total demand for refined products fluctuates from 19M–21M barrels a day, which means that we are still importing products (especially into PADD 1, which has broad shortfalls keeping the arb open into the region). The SPR release does little to change that because our imports typically come from Europe and the Middle East, and the crude being pushed into the market will end up in Asia.

The 32M being released is a sizeable number when we consider it is in addition to current production and exports globally speaking (it is a month’s worth of Angola production, for example)—but the quality remains the biggest hinderance to its underlying effectiveness. West Africa produces a large amount of medium sweet, which should be in high demand, but they are currently sitting on a record amount of crude in storage. Asia has been slow to buy crude at these prices and underlying OSPs (Official Selling Prices), and instead have been trying to pull down more from inventories. They have been taking contractual allocations, but not picking up any spot cargoes given the cost of refining and underlying OSPs. Asia is always bargain hunting (especially China), so they could pick up some of the cheaper U.S. SPR barrels in the near term.

Countries are trying to find ways to address the “emergency” that has become accelerating inflation, and the SPR is just one of the tools attempting to bridge the gap into expected 2022 builds. West Africa has struggled to sell their loading programs for months now and have even reduced their production well below the levels allowed under the OPEC+ agreement. There has been a broad disconnect between the physical and futures market given the expectations of builds next year as supply rises out of OPEC+. Typically, the first quarter of the calendar year has the lowest demand for the year. This was a reason I thought OPEC+ could adjust their current production increases. By making more crude available through an SPR release, there is a hope that this will bridge a gap to slow the rise of inflation as we head into 2022. But, governments continue to misunderstand the refining process.

Unfortunately, inflation is rampant across the global supply chain and crude is only one piece of a much bigger puzzle. It is a VERY important piece, but inflation will remain a problem well into Q3’22—with or without this SPR release. The rise in “sticky” inflation is the biggest cause for concern, because even if the market sees a slowdown in the pace of price increases, we are still far from a normal market.

The pace of “flexible” inflation can normalize, but the elevated levels will keep pulling all inflation metrics higher, keeping the action of an SPR release muted at best.

OPEC+ will maintain their normal production increases in December and January even with the global SPR releases. West Africa is already well below their allowed levels and any pause in OPEC+ production would be to address the record amount of crude sitting in floating storage and the rise of COVID19 cases impacting near-term demand. It will be very hard to get sign-off from the UAE and Russia at this point on a pause in production increases. The best thing OPEC+ could do right now is to maintain production increases while lowering OSPs, because it would help pass on some margin to refiners struggling with elevated costs. This would also help lower the price of gasoline/distillates because their prices are globally set. For example, the price of U.S. gasoline is set by the most expensive incremental barrel, which is imported crude (dated Brent) and not WTI (West Texas Intermediate). Many OPEC+ nations are also facing their own inflation and rapidly increasing cost of food, so the additional revenue brought in from rising exports is a natural way to import U.S. Dollars and manage economic pressures.

Another “fun” idea being thrown around (again) is to ban U.S. crude exports. The average crude run through a refiner is 33 API, while most of the oil produced in the U.S is 35 or greater, with more than half being over 40 API. This means the 3M barrels a day of crude being exported would just sit in a storage tank because most refiners have ALREADY maxed out their ability to process U.S. light-sweet crude. It would also reduce the incentive to invest in U.S. production—realized prices would plummet as product is trapped in tanks with no buyer. There have been comments that refiners can just build new equipment, but that takes years and billions in CAPEX. It would also leave us short some products because light-sweet crude doesn’t have the ability to process into heavy products (asphalts, for example). The reconfiguration isn’t remotely feasible, so the goal needs to be addressing the underlying shortfalls in the market.

Typically, SPR releases are reserved for “emergencies,” which means the government is looking at price and underlying inflation as such. But there are other steps that the government could take to address rising prices in the market. For example, an easier and cheaper way to counter imbalances between the East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico would be to temporarily waive the Jones Act. This is an emergency response often taken after hurricanes, which allows non-U.S. flagged, built, and manned vessels to transport products between U.S. ports (i.e., this would allow a vessel flagged in the Caribbean to move product from Houston to New York Harbor). The government can make it cheaper to process and move products between U.S. ports and help alleviate specific shortfalls in the market. They can also temporarily waive EPA guidelines to make it cheaper to process crude. Environmental regulations add another layer of pricing to refined products, and adjusting them temporarily would help alleviate near-term costs. This would cause the least amount of damage during the winter months, where regulations are already at their lowest due to the atmospheric changes in the winter vs summer. For years, we have slowed down the progress of building pipelines to address broad disconnects in the market—especially between the U.S. and Canada. Building pipelines is a longer-term solution to provide reduced pricing because it would deliver heavier crude directly to the market that needs it the most: Gulf of Mexico refiners. These are examples of short- and medium-term solutions that we could enact to tackle the problem of rising prices, but we must act now.