SUMMARY

• Quick Crude and Earnings Summary

• U.S. Completions Activity

• OPEC+ Meeting and Physical Market Update

• Russia-Ukraine Deep Dive and My Base Case Scenario

• Brief China Roundup

• Quick Crude and Earnings Summary

Crude surged again today with focus remaining on Cushing as the spread between WTI-Brent collapsed. I go into more detail later, but the quick summary is- European buyers have stopped purchasing Urals driving down diffs to -$3. This is allowing more U.S. crude to move into the European markets even as the spread limits/stops exports into Asia. In a “normal” market, the tightness between WTI-Brent would shut down exports, but as long as Russia-Ukraine remains in focus- we will see steady flows into Europe. The spreads will also support additional buying from Nigeria into Europe/U.S. given the differentials. Spreads out of Nigeria have weakened, which just makes it even more attractive to move more barrels into the Atlantic Basin/ GoM. On a side note, I outlined last week how the Fed has a dual mandate: full employment and inflation. We had a very strong jobs number today with a BIG revision higher in January that will support rate hikes at the next meeting as well as the end to QE next month. This will support the USD and push yields higher that will add to the uphill battle for broader commodities. I think the dollar holds firm at these levels with a steady move back to the highs of 97 as the 10-year approaches 2%. This will be a broad pressure point for commodity prices as the expectations for a Chinese resurgence is overblown on a broad spectrum. On a positive crude note, at $92 a lot of acreage becomes profitable, and supports the commentary we have already heard from the majors (more on that below).

As we progress through Q4 earnings and hear about future drilling plans, we are getting color around expanding activity within the U.S. Chevron, Exxon, and ConocoPhillips have all spoken about production growth throughout 2022. Our view was for an exit rate in ’21 at 11.7M barrels a day (at the top end) and an exit rate in 2022 at 12.2-12.3M barrels a day. This works out to 500k to 600k barrels a day of growth over a 12-month period, but the CEO of COP Ryan Lance upgraded his forecast on growth to 900k barrels a day following commentary from the majors. We discussed last week how the public companies are just getting started, and they will be the key growth drivers over the next 12 months. While I think 900k is possible, I am sticking with my increase estimate of about 500k-600k barrels per day. If I factor in growth in liquids production, I get to his 900k number so it could easily just be semantics on U.S. production increases. This is the chart we referenced last week:

Exxon and Chevron have talked about growing Permian production and bringing rigs/spreads back to work. Here is just a sample from the CVX call:

“A – Michael K. Wirth

Yes. So, let me speak first to activity. And then I’ll let Pierre, who’s now in charge of our supply chain organization by the way, speak to any signs of inflation in how we’re managing that — activity in the Permian is really increasing, aligned with the guidance that we’ve issued previously and spending this year up from $2 billion to $3 billion wells put on production a little bit over 200, we anticipate this year, which is up about 50% versus 2021 and we’ll share an update on all of these things when we see you in March.

So, I would say this is really very well aligned with what we’ve already guided to and indicated, and reflects the ongoing efficiencies that we continue to see in the field and just the quality of this asset, which endures as we go through cycles like the one we just went through. It’s really quite nice to have an asset in your portfolio that is this large. That’s this flexible when it comes to capital and that we can demobilize, remobilize, not that we would intend to do this frequently. But when conditions call for it, we’ve been able to exercise that flexibility here over the last couple of years. So strong progress there and I’ll let Pierre comment on input costs.

A – Pierre R. Breber{BIO 18332161 }

Jeanine, we continue to manage our costs. We think very well in the Permian and across our portfolio, our capital budget, which we announced in December expected some COGS increase, modest in the low single digits and what we might be seeing a little bit more than that in the Permian, it’s very manageable and we think we can offset with efficiencies.

So, as we’ve talked about although rates are up, there’s still below where they were pre-COVID on rigs, capacity in the industry for specific oil and gas, equipment services is still below pre-covid levels. So, whereas we are exposed to labor and steel, and certain other elements, cost elements that are tied to the broad-based economy, oil and gas specific equipment. Services are still well under control and our ability to contract well be a very good partner to work with all gives us confidence that the little bit of cost pressure we’re seeing is a very manageable within the range of what we expected, and we intend to deliver our capital program in line with our budget.”

A – Kathryn A. Mikells Unsurprisingly with the size of our upstream business relative to downstream and chemicals, the biggest increase year-over-year comes from over all the upstream business and further spending in Guyana, further spending in unconventional, especially the Permian, beginning to up weight our spending over all on our own emission reductions, and again, the Permian would be another place that we’re particularly focused, restarting paused projects, that we had in the downstream. And then, you’ll be well aware of the big projects that we have ongoing in chemicals. So, that’s really what’s driving the difference and I’d say how we think about landing towards the middle versus a different and within that range. But obviously, tightening the range relative to the range that we’ve given over a longer period of time, which is the $20 billion to $25 billion.

A – Darren W. Woods: So we grew our Permian production from 2020 to 2021 by over 25%. Our expectation as we go into 2022 is to grow another 25%. And that’s, when you’re doing that with a very tight control on capital. So that’s how we’re playing the game and we continue to look at within our — the approach that we outline a couple of years ago and the success that we’ve seen with that and bringing to bear a lot of the technology and application expertise, I think, drilling and reservoir managing, the rest of the corporation has really seeing the benefits of that.

• U.S. Completions Activity

These are just two operators in the Permian that are going to drive up more activity in the U.S., and when you factor in the privates that have a head start- to see 500k barrels of growth in the U.S. to close out the year is a conservative estimate. “ConocoPhillips is concerned about overall levels of U.S. oil production growth getting too big, especially after recent announcements of Permian Basin increases from Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. The U.S. will add as much as 900,000 barrels of oil a day over the course of this year, Chief Executive Officer Ryan Lance said on a conference call, upgrading his prior forecast by about 100,000 barrels. U.S. growth is “right at the front of our mind,” he said. “If you’re not worried about it you should be.”

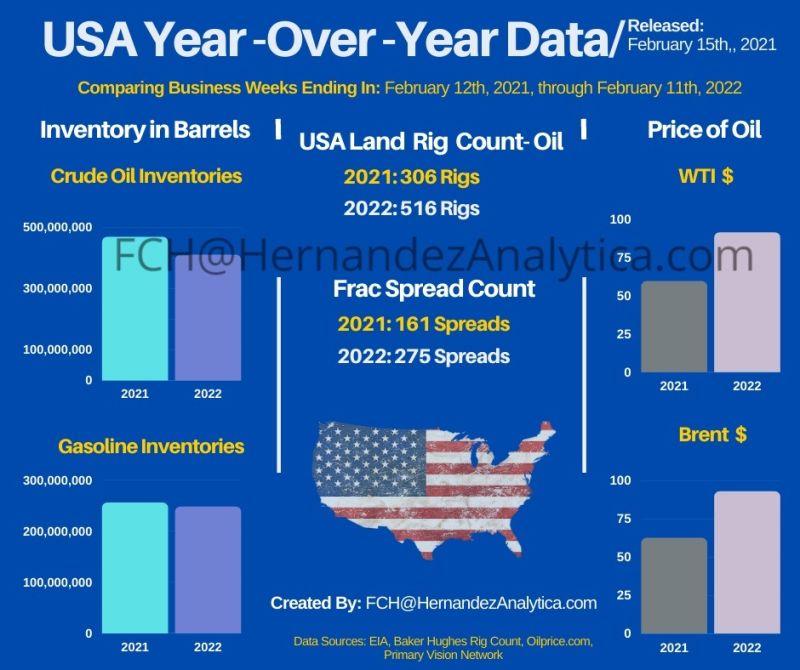

When we add crude and crude equivalent, we are in agreement with COP on their projections, and it will result in additional spread activity especially in the Permian. The move back to 275 spreads is still on pace as we gradually increase activity across the U.S.

The Permian is already outpacing 2020 and will reach ’18-’19 levels by the beginning of March. It is a mixture of easier comps, but also the growing focus on Permian activity driven by the majors increasing activity in the region. We will get to about 150 spreads in the Permian by the time we cross into earlier March. Exxon and Chevron have already increased their CAPEX spend in the region to address the general rise in costs across labor and equipment.

The national spread will keep pushing higher along the rate of change we saw in 2017 as there is a steady addition of activity in key growth areas: Permian, Western Gulf, TX-LA-SALT, and Anadarko. We are expecting to see an increase in crude production by about 500k barrels a day with another 500k barrels of liquids production coming to market. The blend between the two may vary, but we are well positioned to see steady growth in 2022.

The commentary from the majors gives us confidence that we will get to 275 in short order, and there will be enough CAPEX to get additional spreads back into the market. This will get us to 300 by the beginning of the summer for a strong push throughout the summer months. The price of crude and liquids remains supportive of additional activity across the U.S.

• OPEC+ Meeting and Physical Market Update

The OPEC+ meeting happened exactly as we have broken it down before with just another 400k barrel a day increase allowed. The additional 400k barrels a day that is allowed to be produced is a target number while the countries in OPEC+ use the market to dictate how much should actually come to market. The excessive floating storage in Asia and West Africa has limited the amount of new production that has come to market over the last few months. We have seen the physical market start to widen a bit depending on the grade and originating seller of the crude. Some European refiners have paused buying urals for fear of sanctions against Russia and being stuck with cargoes they can’t use or sell. This has caused some broader disconnects in the market, which is complicated further by the Lunar New Year and extended downtime in China. The spreads will also be driven by the type of refined products that can be produced from each cargo. Crudes that are heavy in middle distillate (diesel) will have the higher bid given the demand shifts in the global market. Middle Distillates remain the bright spot as storage levels for gasoline (light distillate) and residual fuels (heavy distillate) wane given the elevated amount of product in storage. The prices of middle disty will keep the FCC margins elevated, but as gasoline demand remains weak and storage builds- it will create a different problem for refiners. When you make 1 barrel of diesel it inherently creates 2 barrels of gasoline, which has to be accounted for and is resulting in big builds around the world. Given the current spread, refiners are fine running their cracks as hard as possible to capture the middle of the stack but unless we get a big surge in gasoline demand come March/April- we will be floating in a sea of gasoline.

Unipec bought two Urals cargoes at lowest prices in more than six months. Litasco and Glencore offered CPC Blend.

PLATTS:

• Urals:

o Unipec bought 100k tons for Feb. 14-18 delivery from Gunvor at Dated -$3.15/bbl, CIF Rotterdam: trader monitoring Platts window

o Also bought same amount from Litasco for Feb. 17-21 delivery at Dated -$3.10/bbl

• Traded prices were the lowest since mid-July, compared with -90c for previous deal on Jan. 17

• CPC Blend:

o Litasco offered 85k tons for Feb. 20-24 at Dated -$2.10/bbl

o Glencore offered 94k tons for Feb. 22-26 at -$2

o Petraco withdrew offer for 90k tons for Feb. 19-23 at -$1.95

o Equinor withdrew bid for 85k tons for March 1-5 at -$1.45

Nigeria’s crude sales have weakened in the past week, as a few unsold prompt cargoes for February are dampening sentiment, one of the people said; unsold tally not immediately available

• Vitol offered to sell 380k bbl of Nigeria’s Brass crude for Feb. 10-11 loading — to be co-loaded with 600k bbl of Okwuibome for Feb. 16-17 — at $3.65/bbl more than Dated Brent on CFR Rotterdam basis; vessel is Montesperanza: trader monitoring window

o Drops from +$3.90/bbl on Feb. 2, +$4.05/bbl on Feb. 1

About 10 of the 34 Angolan cargoes planned are yet to be sold, said traders with knowledge of the matter

• Unsold tally of March shipments drops from about 17 in estimates compiled on Jan. 27, when sales were running a little faster than normal

• Current pace of sales is largely steady with about a month ago, when 9-11 February shipments were still seeking buyers in estimates compiled on Jan. 6

Republic of the Congo’s Djeno crude is selling well, with 2-3 shipments still searching for buyers out of six scheduled, the people said:

o Drops from 4-5 unsold as of Jan. 27

o Republic of the Congo’s trading cycle runs from about the 24th of each month

The Lunar New Year is impacting the speed of West Africa sales as they will slow down over the next few days- especially for Angola and Congo. As more pressure mounts on Russian barrels, it will support additional movement of Nigeria into the European markets. Libya has also shut down six ports due to weather, but those will come back online quickly. Nigeria had an explosion today on the FPSO Trinity Spirit, but according to state records the owner, Shebah, didn’t produce any oil in 2020/2021 and was in receivership. So, there shouldn’t be any near-term impacts to Nigerian exports and production. U.S exports will struggle to compete into Asia as the spread widens between WTI-Dubai, but as the Europeans pull back on buying Russian crude- it will provide some near-term support. This will move the 4-week rolling average of U.S. exports to about 2.7M barrels a day, but it will still be limited keeping additional crude in PADD3. Imports will remain elevated as heavier crudes are imported to help support the need for middle distillate production.

The crude in transit remains elevated as purchased made in Nov-Jan remain in motion and heading to their end location. Between crude in storage and in motion, we still have a record amount of crude on the water. As additional ships show up at the coast, we will have it transitioning from “in-transit” to “floating storage” once it has been stationary for 7+ days. The level of crude on the water is another key reason that some OPEC+ nations are holding back on hitting their allowed targets.

The elevated amount of storage in this key producing and consuming region has kept some of the actual production levels reduced in key OPEC+ countries. As we see some of these spare cargoes clear, there will be a gradual walk up in some production levels.

The Asian storage will remain a bit elevated as Teapot refiners in China have reduced utilization rates, which will remain depressed throughout the month of February. Between the Lunar New Year holiday and Olympics, activity will remain depressed throughout the rest of the month. They will start to increase activity in March but remain below the 2021 levels as import quotas were cut and new facilities come online. When the Olympics end, we will see a pickup in activity, but it won’t be a quick recovery of the 20% but rather an increase of 10%. The market is factoring in a robust Chinese market/economy, but everything that we look at says those expectations are grossly overblown. China is sitting on a significant amount of all commodities, and the hope is that they eat through spare inventory quickly as we move into March. The issue remains the weakness in their market as well as the underlying consumer.

• Russia-Ukraine Deep Dive and My Base Case Scenario

Russia-Ukraine has a deep history that is filled with a significant amount of distrust and broad blame for the collapse of the USSR. “For three decades, Ukraine has been “a space where the interests of the great powers clashed and yet no conflicts were resolved,” Serhii Plokhy and M. E. Sarotte wrote in 2020. “As long as Ukraine’s status is unsettled and insecure, the consequences will continue to reverberate beyond its borders.” Ukraine was pivotal part of the USSR with over 85% of their nuclear and ballistic missiles being built and assembled in the country. As the USSR collapsed, Russia tried to setup a “union” with the satellite nations, but needed Ukraine to remain a part of Russia to make the plan a reality. Without the Ukraine economy, Russia faced a big drop in economic activity and the ability to keep the fragile union in place. “To most American policymakers, Ukraine has represented a brave young country—one that, despite the burden of history, successfully launched itself on a path of democratic development as part of a new world order after the fall of the Berlin Wall. To the Kremlin, meanwhile, it has remained an indispensable part of a long-standing sphere of influence, one that operates largely according to old rules of power. The difference between these two views goes a long way toward explaining why post–Cold War hopes have given way to the strife and uncertainty of the world today. “Yeltsin, who by then had edged out Gorbachev as the preeminent leader in Moscow, belatedly realized how much he had misjudged Ukrainian desires to break free from the collapsing Soviet empire. After the failed coup, he had been trying to keep Ukraine in the union by threatening Kyiv with the annexation of Crimea and the Donbas. The December vote proved, however, that Yeltsin’s threats had backfired; they had instead stiffened resistance in Kyiv and alarmed the rest of the Soviet republics (and Washington, as well).”

The U.S didn’t want an independent Ukraine either- President Bush gave a speech ahead of the vote describing the different between Independence and Freedom. The backbone of the speech was explaining that you can have freedom WITHOUT independence. The U.S. also wanted Ukraine to remain a part of Russia because we believed it would destabilize the region further as well as create the third largest nuclear power. The Ukraine swiftly voted YES for independence and become the third largest nuclear power in the world. “On independence, Ukraine immediately became a direct threat to the West: it was “born nuclear.” The new state had inherited approximately 1,900 nuclear warheads and 2,500 tactical nuclear weapons. To be sure, Ukraine had physical rather than operational control over the nuclear arms on its territory, since the power to launch them was still in Moscow’s hands. But that did not matter much in the long run, given its extensive uranium deposits, impressive technological skills, and production capacities, particularly of missiles; every single Soviet ballistic missile delivered to Cuba in 1962, for example, had been made in Ukraine.” Yeltsin, who by then had edged out Gorbachev as the preeminent leader in Moscow, belatedly realized how much he had misjudged Ukrainian desires to break free from the collapsing Soviet empire. After the failed coup, he had been trying to keep Ukraine in the union by threatening Kyiv with the annexation of Crimea and the Donbas. The December vote proved, however, that Yeltsin’s threats had backfired; they had instead stiffened resistance in Kyiv and alarmed the rest of the Soviet republics (and Washington, as well).”

In May 1992, Moscow and Kyiv clashed over the fate of the Soviet Union’s Black Sea Fleet, which was based in Sevastopol. A dispute over the division of the fleet and control of the port would drag on for the next five years. As tensions flared, the Ukrainian parliament began making new demands in exchange for giving up the formerly Soviet missiles: financial compensation, formal recognition of Ukraine’s borders, and security guarantees. In order to close this chapter, the US brokered the signing of the Budapest Memorandum to move the missiles back into Russia while giving “soft” security over the border.

This created a new challenge for the U.S and Russia on how to get the weapons out of Ukraine and back into the hands of Russia. We feared that they would fall into the wrong hands. But recently declassified documents show that the triumph was incomplete—something that Ukraine recognized at the time but could do little about. As a Ukrainian diplomat confessed to his U.S. counterparts just before signing the Budapest Memorandum, his country had “no illusions that the Russians would live up to the agreements they signed.” Kyiv knew that the old imperial center would not let Ukraine escape so easily. Instead, the government of Ukraine was simply hoping “to get agreements that will make it possible for [Kyiv] to appeal for assistance in international fora when the Russians violate” them. Having helped denuclearize Ukraine, Washington thought it could largely stop worrying about the country, believing its independence to be an accomplished fact. The reality was that Moscow never truly accepted that independence, in part because it viewed Ukraine not only as a key element of its former empire but also as the historical and ethnic heart of modern Russia, inseparable from the body of the country as a whole.

The Budapest Memorandum could not paper over that disconnect forever. Had the memorandum provided the guarantees of their country’s territorial integrity that the Ukrainians sought instead of mere assurances, Russia would have met with much greater obstacles to violating Ukraine’s borders, including in Crimea and the Donbas. (Another policy alternative would have been to strengthen the Partnership for Peace, of which Ukraine was a member, instead of marginalizing the partnership and promoting NATO’s expansion to a small number of countries.) Before long, the consequences of going without such supports would become clear- as we are founding out now.

After the signing of the Budapest Memorandum, the concerns over the region faded. Russia went into a deep recession and culminated in them losing about 98% of their market value. As the years progressed, President Clinton got involved in Bosnia. The U.S. went on a bombing campaign to target strategic assets, but we were considering the deployment of troops and ground assets to the region. As we were deliberating, Russia sent in a column of tanks and troops and warned the US to stay out of the region. This was their “reemergence” on to the world stage. This strained relations, but the US backed off and let Russia handle the situation.

The situation between Russia-US deteriorated further when: In March 2004, NATO accepted into its ranks the three Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—which were once part of the Soviet Union, and four other states. The accession of the Baltics signaled that NATO enlargement would not halt at the former border of the Soviet Union. The EU followed suit in May 2004, extending its border eastward to include a number of former Soviet republics and allies, including the Baltic states, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Since Putin, a leader of an empire denying its own decline, still considered Soviet borders significant, he viewed such moves as a massive affront. This movement enraged Putin as NATO moved closer to their underlying border. In response, Russia moved into Georgia in 2008, and “officially” reestablished themselves as an entity to pay attention too.

Fast forward to Syria where Russia came in to backstop the Assad government and turned the tide of the war in favor of Assad. This gave them a much bigger footprint and sphere of influence within the Middle East as they get more involved in global geopolitics and look to protect their economic interest. As the Sochi Winter Olympics neared, the Russian military was moving new assets into the region claiming “security” around the Olympics. But Russia/Putin was losing a lot of influence in Ukraine after his “guy” was voted out of office. Within Crimea, unmarked soldiers started patrolling the streets and things started to become a bit hairy when the Olympics ended, and the military kept a significant amount of assets in the region. Within a month, they had moved straight into Crimea and “Claimed” it as their own. This gave them significant control of waterways but resulted in broad sanctions from the international community- especially around Nordstream 2. Crimea has always been mostly Russian, so the international argument was- “well- they already speak Russian there and they have a Russian lineage.” Russia still faced sanctions, but Ukraine-Russia still maintained some economic cooperation regarding agriculture, industrial, and the sale of oil/gas through pipelines.

In 2014, Ukraine was disorganized and struggling to establish a sound government. In 2022, the country is way more organized and unified, which doesn’t make it easy for Russia to just “walk-in” like they did in Crimea. NATO and allies have sent equipment, advisors, and some troops to Ukraine to aid in their underlying support. Ukraine sits surrounded on all three sides by Russian military assets, and there are two distinct ways how this ends.

Base case: Putin is looking to protect economic/geopolitical interests by establishing the ability to muster a strong military response.

1) Putin wants NATO to stop admitting new countries into its ranks- especially the ones bordering Russia.

2) Specific NATO (US) equipment can never reside in bordering nations- IE THAAD

3) Sanctions have to be lifted against the Russian sale of natural gas/crude into the European markets- IE approve Nordstream2

4) Demonstrate to China that Russia can move military assets quickly across long distances

5) Provide a way to distract from a struggling economy and other local economic issues that continue to compound within Russia.

The 4th point is very important. Back in 2017- Russia invited Chinese advisors to come watch the war games in the eastern part of Russia. It included all three branches of the military and 54k troops that were responding to an invading force. For those confused, only China could possibly invade that part of Russia. This followed closely to the declaration of China’s 9-dash line that claims large parts of Russian territory as their own- including oil/gas assets and key ports for the navy and trade. After Chinese soldiers attacked Indian soldiers in Ladakh, Russia was the first country to side with India (after only 1 hour after the attack). Russia also sped up the delivery of S-400s, aircraft, and other equipment/training to the Indian military. As you read this, the Indian military is currently training within Russia on how to use the equipment. China has also been building new assets and nuclear missile silos within striking distance of Russia, which keeps things very tense between the two.

Putin needs the US to help counter Chinese expansion and military growth- so it is unlikely that anything progresses past one clash. There is too much equipment and personnel at the border to not have one brief battle that results in deaths on both sides. This will be the “flash point” of the conflict, and olive branches will be sent on both sides resulting in de-escalation where everyone “gains” something.

Why would Putin/ Russia attack?

Putin has been trying to re-establish the USSR and Russia’s prominence on the world stage. He blames the Ukraine for driving the death nail into the USSR/Russia following their independence. Putin has lost most/ if not all influence within the Ukraine government, and he is looking to bring them back into the ranks. This could very easily be a “pride” play and a way to effectively distract from the economic woes at home. If he does move, it will have to happen within February because as we get into March the ground will start to thaw, and no longer be able to support the weight of the heavy machinery, tanks, armored vehicles, etc. Russia would be picking up a lot of manufacturing, agriculture, and fertilizer exposure. It would also link some key pipelines and embolden Belarus. The problem is- the local populace would launch a counter military movement that would rival the French underground. Ukrainians would make life very difficult for the Russians and given the weakness in their economy- it would prove very costly.

Everything is a possibility- but it has to be measured. Russia has moved blood and medical equipment to the front lines, which is normally a precursor to an invasion. But, all of their movements have been well telegraphed and eliminates any type of surprise attack. I struggle to see how Putin would win at the end of the day invading.

Putin/Russia also has a huge advantage because the U.S. and Europe rely on them for oil, refined products, and natural gas. Putin (being a true bond villain) is playing his hand aggressively as the U.S. has increased their imports of diesel and urals. The U.S. is drawing more diesel from Russia this month than it has in at least three years as cold weather envelops the Northeast. About 1.55 million barrels of diesel is en route from Russia to the U.S. for February arrival, a record in data going back three years, according to oil-data provider Vortexa. So far that represents 22% of the nation’s diesel imports in February.

Russia has also been building their gold and foreign exchange reserves to help buffer against sanctions and increase the demand for the ruble. They have also reduced their foreign debt holdings to limit the severity from Western sanctions- especially on banking/USD access.

At $634 billion, central bank reserves are close to a record, thanks to policies that saved much of the oil windfall in a rainy-day fund. The budget ran a surplus of 0.4% of GDP last year and government debt at 18% of GDP is among the lowest of major economies. Moscow has reduced dependence on the dollar for trade and transactions and is building up its own alternatives to U.S.-dominated payment systems. Thanks in part to those defenses, economists say that the likely sanctions would knock the ruble as much as 20% lower against the dollar, fuel already-high inflation and thus require more interest-rate increases by the Bank of Russia, as well as possibly intervention to support financial markets and sanctioned banks.

These moves will insulate some of the damage of new sanctions, but it will still cause a broad drop in the ruble. Russia and China have agreed to extend their trade relationships across crude and natural gas, but would China accept transactions in Ruble? That would become the biggest unknown- if they do- it would buffer a lot of the expected drop (with a lot of it already baked in). If they didn’t, it would cause a huge problem for Russia but also China. China relies extensively on their natural gas and ESPO/ Sokol grades, so it is likely that China would play ball and accept transactions in Yuan/ Ruble.

• Brief China Roundup

Brief recap on the Chinese consumer and data sets- new orders and employment have all weakened throughout China. As wages weaken, retail sales slow, and inventory builds- the Chinese economy is facing more uphill battles that aren’t going to end any time soon. The “stimulus” that the CCP has launched will just help stabilize the decline, but is no where near enough to reverse the decline.

The biggest leading indicators (especially for an exporting nation) are in contraction and have been for several months. This is compounded by the steep decline in employment across both sectors.

We have been discussing the big drop in employment over the last 12+ months, but the big drop in manufacturing employment is just going to add pressure to what has already been weak since 2018- Non-manufacturing employment. It has resulted in a big build up of inventory and a slow down in general savings rates- IE less ability to spend.

The pressure on the local consumer is hitting the small businesses the most at this point as small firms keep getting crushed in China. Large firms are normally big exporters and are more insulated from the declines, but the small firms (mostly selling local) are showing how deep the cracks run. It is also a key reason why the CCP wants to try to support the smaller firms.

These impacts are going to hit businesses hard as operating income diverges and puts more pressure on the broader economy.

The still fast but braking corporate income trend hides a very important feature, namely the sizable gap between the mean and the median of the growth rates. This means there is a growing divergence in better performance in large firms versus lagged improvement in small firms. China isn’t coming to save the global market again… buckle up!