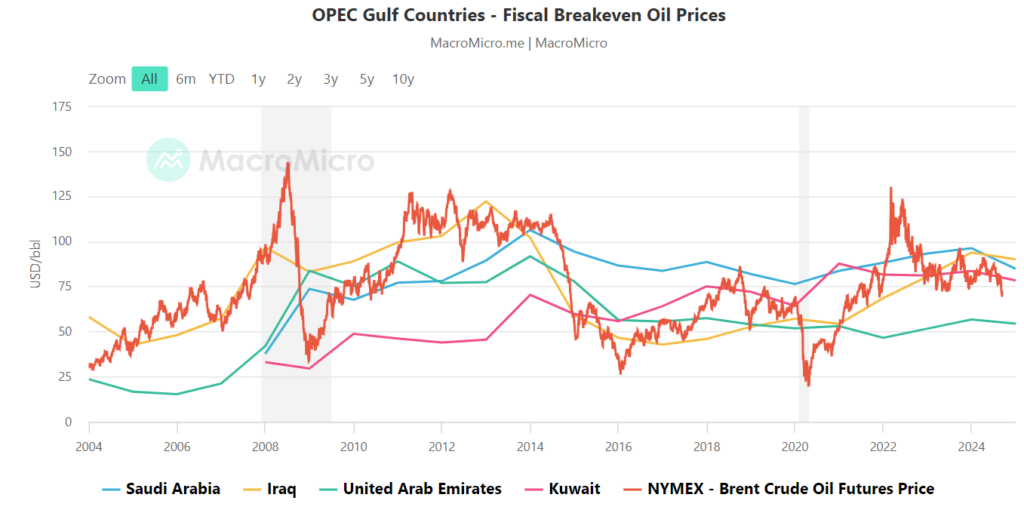

The million-dollar question for OPEC right now revolves around what the organization will do next as they seem to be running out of options. Global oil prices have slumped dramatically, and as the charts you’ve uploaded indicate, OPEC members are now facing a stark disparity between their fiscal breakeven oil prices and the current market prices. This widening gap, combined with mounting economic pressures within member nations, raises the question of whether the existing production agreement can hold or if we could witness cheating or a potential collapse in the agreement.

Let’s dive into the critical analysis of this situation, starting with the figures. Saudi Arabia’s fiscal breakeven oil price has climbed to $96.20 per barrel for 2024, and it could rise even further, potentially around $100 if oil consumption in China remains weak or other global economic indicators continue to falter. Right now, Brent crude is trading around $73 per barrel. This means Saudi Arabia is staring at a $23-per-barrel shortfall against its breakeven price, putting significant pressure on its budget. To put it bluntly, the math doesn’t add up, and this isn’t just an issue for Saudi Arabia. Iraq, OPEC’s second-largest producer, is facing similar difficulties. Their fiscal breakeven oil price is expected to surpass $90 per barrel this year, and the IMF has already warned that Iraq could face a widening deficit if oil prices remain subdued. The outlook for Iraq is particularly concerning, with public debt expected to almost double from 44% of GDP in 2023 to 86% by 2029. These rising breakeven prices represent an existential dilemma for OPEC members, especially in a world where the global demand for oil appears to be softening.

The reason behind the downward pressure on oil prices stems from various factors, but most notably, it’s due to a slowdown in global demand. The U.S. Federal Reserve is expected to cut rates by 50 basis points in the near term to stave off a recession, and this slowing economic activity is dragging down oil consumption. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global oil demand growth has already slowed significantly, and with China, the world’s largest oil importer, still grappling with an economic downturn, OPEC faces a tough battle to maintain oil prices at the levels they need to balance their budgets.

Now, let’s take a closer look at the situation in China. China’s imports of crude oil increased to 11.02 million barrels per day in August, up from 9.97 million in July. However, this increase may be short-lived, driven more by stockpiling ahead of the winter rather than an actual uptick in demand. Chinese refineries have been adjusting their crude purchases in response to price fluctuations, but with weak industrial output and plummeting home prices, it’s hard to see how Chinese demand will sustain itself at these levels in the months to come. According to the latest IEA oil market report, world oil demand is set to rise at its slowest pace since the pandemic.

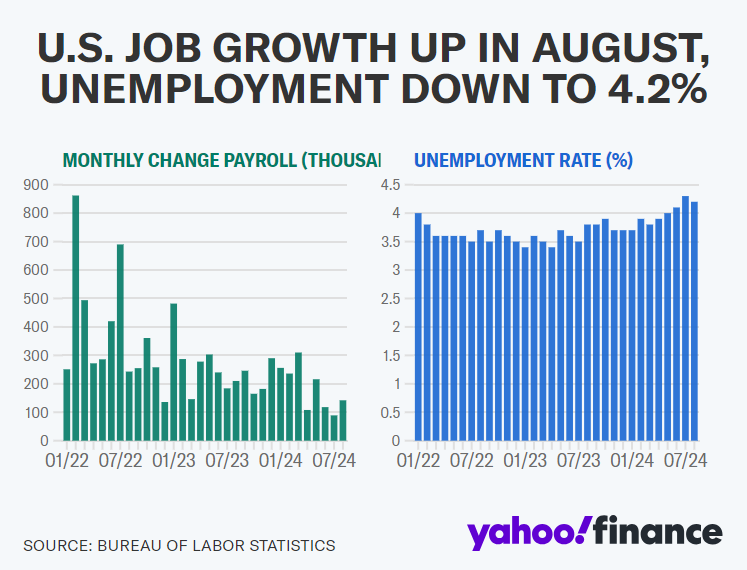

This situation is exacerbated by the U.S. jobs report, which showed that only 142,000 jobs were added in July—significantly fewer than the 161,000 expected. With U.S. manufacturing also slowing down, as indicated by the ISM, there are clear signals of a slowing global economy. These signals add more pressure on oil markets, as fears of recession typically lead to reduced energy consumption.

Given this backdrop, OPEC finds itself in a precarious position. The organization has already extended its voluntary production cuts, most notably a 1 million b/d cut from Saudi Arabia and 700,000 b/d from other members, until November. However, even these cuts have not been enough to stem the tide of falling prices. What lies ahead? OPEC might need to contemplate deeper cuts to stabilize the market. However, such a move is fraught with risk. As we saw during the oil price war of 2020, when the agreement between Saudi Arabia and Russia collapsed, the consequences of an all-out price war could be devastating. Iraq, for instance, has already been overproducing beyond its OPEC+ quota, and it’s agreed to make up for this by cutting more in the future. But how long can such commitments hold when the economic stakes are this high?

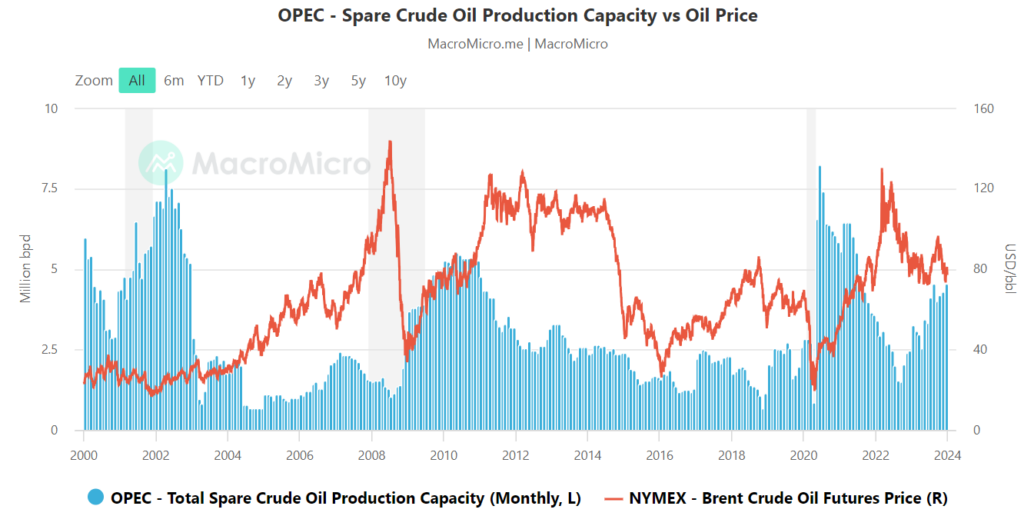

The following chart illustrates the spare crude oil production capacity in OPEC against the oil price, showing how OPEC’s capacity has often cushioned the market during supply shocks. But the problem now is demand, not supply, and that changes the equation. OPEC’s spare capacity is largely irrelevant when global economic activity is slowing, and without a clear demand-side recovery, any production cuts could merely serve to slow the inevitable price slide, not reverse it. Saudi Arabia, with its growing fiscal deficit, may still have some leeway due to its foreign reserves, which reached a 20-month high of $452.8 billion in July. But this cushion won’t last forever, especially given the kingdom’s ambitious Vision 2030 projects and hosting of major global events like the 2034 World Cup. Moreover, the kingdom’s public debt has grown significantly in the past decade, and while still low by global standards, it’s a clear sign that even the wealthiest OPEC members are feeling the pinch.

OPEC+ is standing at a critical juncture. The fiscal breakeven prices of its members are rising while global oil prices continue to fall. With no clear signs of demand recovery, particularly from China, and a slowing global economy, OPEC faces the very real prospect of its current agreement falling apart. If members begin cheating or if the global economy contracts further, we could see a repeat of the chaotic price war that rocked oil markets in 2020. The coming months will be crucial, and OPEC will need to act decisively to avoid a collapse.