This week’s economic data isn’t just about growth or inflation—it’s about what happens when they collide. We’re at the edge of a classic macroeconomic dilemma: softening economic activity, sticky inflation, and deteriorating consumer sentiment. That’s textbook stagflation. We’re not in the 1970s, but the structure feels eerily familiar. In the U.S., inflation expectations are creeping up even as leading growth indicators soften. Europe is looking fragile, with consumers turning deeply pessimistic and industrial data still below water. Even in China, where headline PMIs suggest stability, deeper structural weaknesses persist. What’s alarming is the shift in sentiment—consumers across the U.S. and EU are flashing red. That’s usually the canary in the coal mine. So while headlines remain cautiously optimistic, the undercurrent is far more concerning.

United States

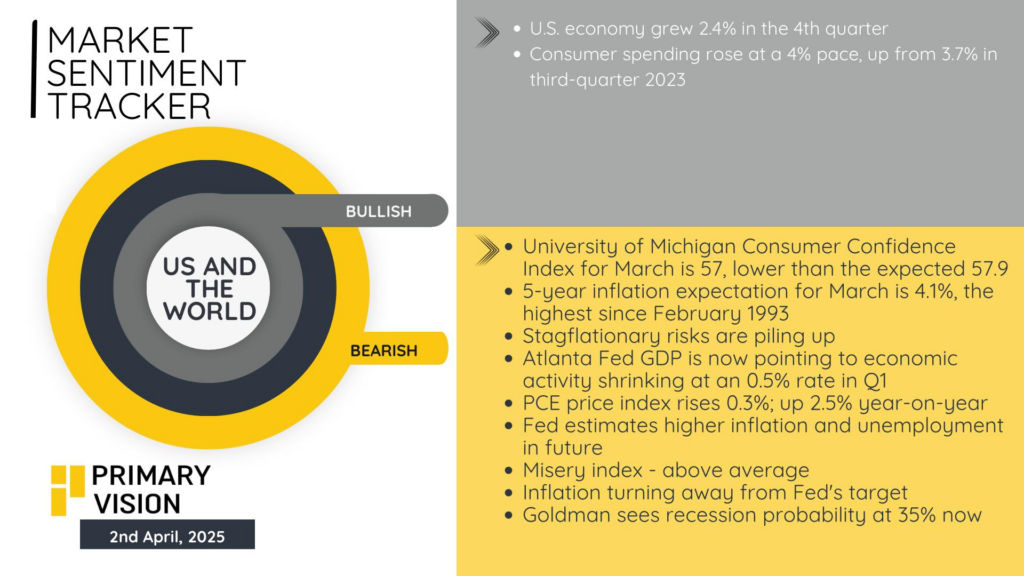

On the surface, the U.S. economy still looks alright. Q4 growth came in at a healthy 2.4%, and consumer spending remained strong at 4%—numbers that ordinarily would bolster optimism. But a closer look reveals emerging vulnerabilities. The University of Michigan Consumer Confidence Index dropped again in March to 57, well below February’s 64.7 and beneath expectations. Worse still, five-year inflation expectations jumped to 4.1%, the highest reading since 1993. That’s the kind of figure that starts to shift central bank thinking.

The Fed’s own projections are inching upward on both inflation and unemployment, while the Atlanta Fed GDPNow tracker points to a contraction of 0.5% in Q1. In other words, the market is seeing a slowdown, the Fed is seeing a slowdown, and yet inflation is still uncomfortably above target. That’s the worst of both worlds. The PCE price index rose 0.3% month-on-month and is now running at 2.5% y/y, edging away from the Fed’s 2% target again. Add in Goldman Sachs revising the probability of a recession to 35% and a rising misery index, and we’re left with a toxic blend: economic deceleration paired with rising price pressure. That’s not recession. That’s stagflation-light.

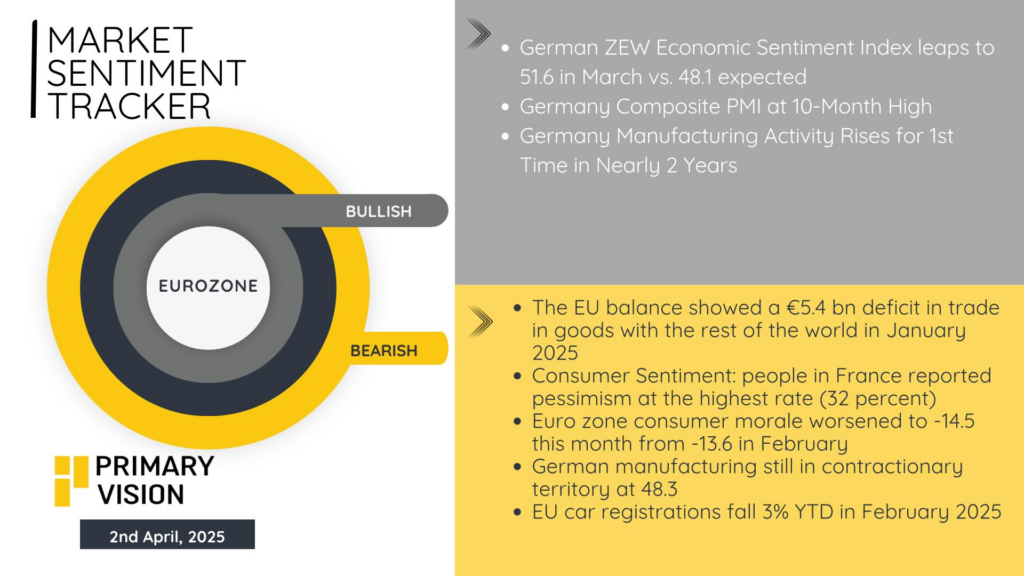

Eurozone

Europe isn’t looking any more encouraging. Consumer sentiment is sliding deeper into pessimism, with the Eurozone confidence index falling to -14.5 in March from -13.6 in February. French consumer negativity has reached new highs—32% of households now express a bleak view of their financial future, the worst reading in the bloc. This is showing up in the data: EU car registrations are down 3% YTD and German manufacturing remains in contraction, clocking in at 48.3. And while the EU balance of trade shows a widening deficit (€5.4 billion in January), internal demand doesn’t appear strong enough to compensate for weakening external demand.

That said, Germany is offering a few bright spots. The ZEW Economic Sentiment Index came in at 51.6, well above expectations, and its composite PMI reached a 10-month high. Manufacturing activity even expanded for the first time in nearly two years. This could be a turning point—but without stronger consumer demand across the Eurozone, the upside may remain limited. Europe’s challenge right now is structural: weakened confidence, stubborn inflation, and a policy stance constrained by fragmentation and fiscal rigidity.

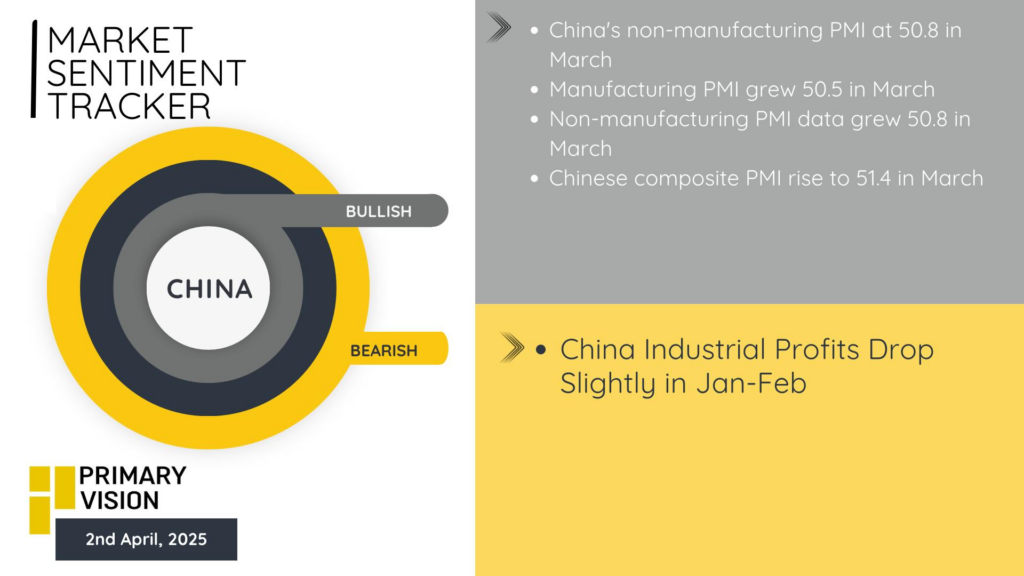

China

China’s data this week looks decent, but context is everything. Manufacturing PMI ticked up to 50.5 and non-manufacturing hit 50.8—both indicating mild expansion. The composite PMI at 51.4 suggests a broadly stable macro backdrop. Retail sales and industrial production were both solid in the January-February period, and Beijing has made it clear it intends to “vigorously boost consumption” through wage support and household de-leveraging.

But behind the growth lies persistent pressure. Industrial profits declined again, signaling weak earnings and margin compression across key sectors. This matters because China’s post-COVID recovery has been uneven: retail sales and services are doing okay, but manufacturing is still weighed down by overcapacity and soft global demand. And deflationary risks are simmering—February saw the fastest decline in consumer prices in over a year, and that could worsen if domestic demand doesn’t pick up materially in Q2. Policymakers are balancing support with restraint, but structural cracks remain—and the longer they linger, the more they feed into global disinflationary forces.