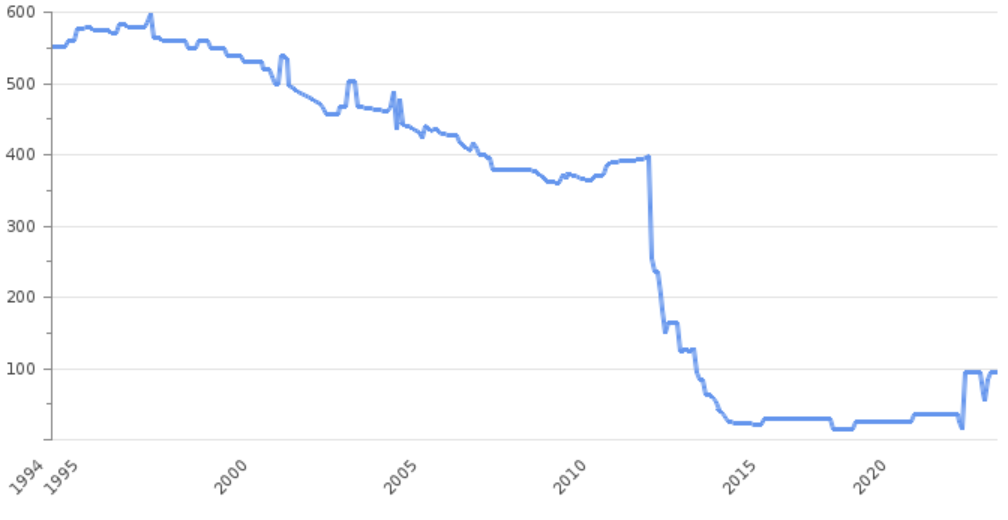

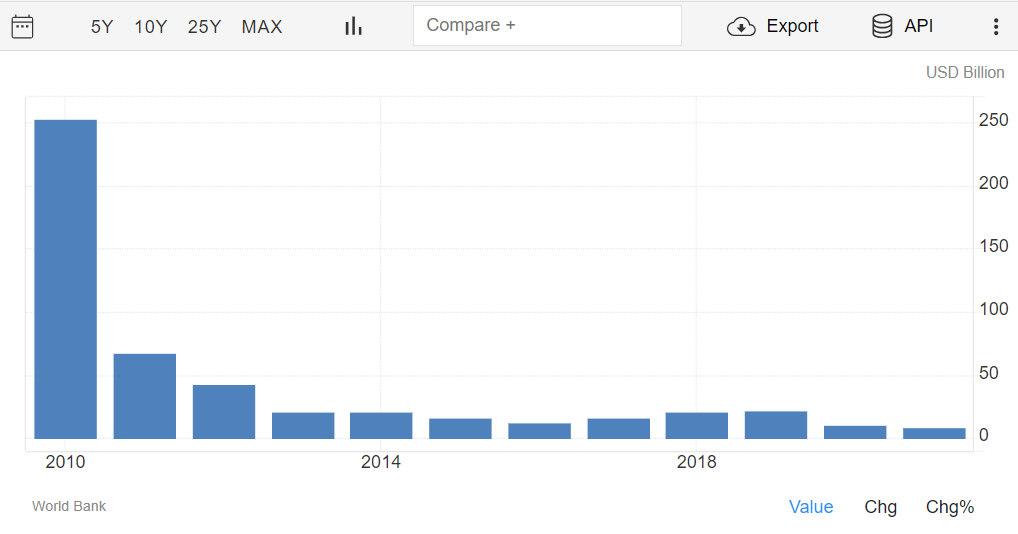

Syria’s oil and gas sector, once a critical economic pillar, now faces a complicated and uncertain path forward following the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. The energy industry, already decimated by more than a decade of civil war, is confronted with extensive infrastructural damage, fragmented control, and geopolitical complexities. Before the conflict began in 2011, Syria produced about 383,000 barrels per day (bpd) of oil, contributing roughly 25% of government revenue. By 2023, production had plummeted to an estimated 40,000 bpd, underscoring the immense toll of war, sanctions, and mismanagement.

At its peak, Syria’s oil and gas sector was a significant contributor to the national economy, sustaining domestic energy needs and generating export revenues. The civil war, however, shattered this stability. Oil fields, primarily located in the east of the country, became battlegrounds, with various factions vying for control. At one point, ISIS leveraged these fields, generating an estimated $500 million annually from crude sales, primarily to local traders. Post-ISIS, control shifted to the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), who now manage a substantial portion of Syria’s oil reserves, particularly in the resource-rich Deir ez-Zor governorate. This region accounts for approximately 40% of the country’s oil reserves but remains a focal point of contention as Turkish-backed rebel forces gain ground. The Assad regime’s reliance on Iranian oil imports—approximately 121,000 bpd as of late 2023—highlighted the crippling effects of international sanctions on Syria’s ability to sustain domestic energy production. These sanctions, imposed largely in response to the regime’s actions during the war, rendered Syria unable to export oil since late 2011. The collapse of Assad’s government has renewed calls for easing these restrictions to enable post-war reconstruction, though geopolitical realities suggest this will be a protracted process.

The immediate aftermath of Assad’s fall saw the establishment of a transitional government under Mohammed al-Bashir. One of the new administration’s primary challenges will be to stabilize the energy sector and address the infrastructural damage sustained during the war. Most of Syria’s oil fields are either inoperable or operating at minimal capacity. Refineries in Homs and Banias, with respective capacities of 107,100 bpd and 120,000 bpd, struggle to meet domestic demand, which currently averages 100,000 bpd. Despite the sector’s dire state, opportunities exist for revival. Experts like Robin Mills of Qamar Energy note that oil revenues could play a crucial role in Syria’s reconstruction, provided central authority is restored. However, parallels with Libya and Yemen caution against fragmented control over resources, which could exacerbate existing divisions and fuel further conflict. Without cohesive governance, rival factions may leverage oil revenues to fund militias or consolidate power, perpetuating instability.

Global energy companies that suspended operations during the conflict, such as Canada’s Suncor Energy and the UK-based GulfSands Petroleum, may cautiously eye re-entry should sanctions be lifted and security improve. Suncor’s Ebla project, which once produced 80 million cubic feet of natural gas daily, and GulfSands’ assets in northeast Syria are among the dormant projects that could be revitalized. However, the extensive damage to infrastructure and logistical challenges will require substantial investment and time. The geopolitical landscape further complicates the sector’s recovery. Russia’s naval base in Tartus, a strategic asset, remains under Russian control, and it is unclear how Moscow’s interests will align with Syria’s rebuilding efforts. Meanwhile, Iran, a key backer of the Assad regime, faces its own challenges, potentially limiting its ability to support Syria’s energy sector as it has in the past.

On the international stage, Syria’s energy potential is unlikely to significantly impact global markets in the near term. Analysts, including Christof Rühl from Columbia University, argue that the country’s diminished production capacity poses minimal threat to supply stability. The focus, therefore, will remain on domestic reconstruction and securing energy independence.

The transitional government’s priority must be restoring functionality to key oil fields and refineries while fostering an environment conducive to investment. This includes negotiating with international stakeholders to ease sanctions and attract funding for infrastructure rehabilitation. However, achieving these goals requires navigating complex political, social, and economic dynamics, ensuring that resources benefit all Syrians rather than perpetuating inequality or conflict. Syria’s oil and gas sector, while no longer a regional powerhouse, holds the potential to drive post-war recovery. Realizing this potential will depend on political stability, effective governance, and the ability to rebuild relationships with the international community. For now, the road ahead remains fraught with challenges, but the sector’s revival could mark a critical step toward a brighter future for Syria.