By Mark Rossano (Originally Published Feb 26th, 2021)

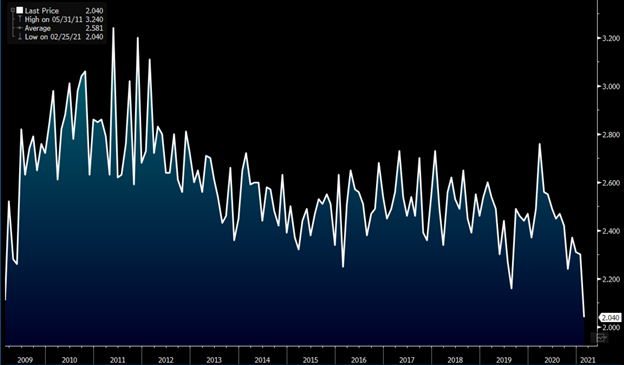

The most recent U.S. 7 Year Note auction saw the least amount of interest it’s had in the last 12 years. I have said increasingly in the past few months that a “failed” auction would mark the end of the central bank experiment. What happened Thursday shows that things are starting to shift in this direction. One weak auction doesn’t make a trend, but we have seen consistent weakness in the amount of investors or bidders showing up. Why is this happening? Who wouldn’t want the safest asset in the world? Is there a lack of demand in the market—have we exhausted all the buyers in the world? Are inflation fears catching up and investors will only buy if it is at a higher rate? As we look at some of these metrics, I will provide some answers and what I think will happen over the next few months.

U.S. 7 Year Note Bid-to-Cover

I will pick on the U.S. to simplify the article, but many countries are facing the same fate, and global yields are reacting with parabolic moves. The below chart shows that the amount of stimulus being pushed into the market pales in comparison to the Great Financial Recession. So why does the market suddenly care about rates after ignoring them for weeks?

Governments that run a deficit (and if you have not been paying attention: OURS IS MASSIVE) have to not only roll current debt, but also issue new bonds/treasuries/notes to pay our bills. Does the sheer size of our debt level make us no longer safe, or least a riskier asset? We have been issuing a ton of new debt to provide stimulus, but the last push comes at a precarious time. Inflation is finally rearing its ugly head (Ssshhh: it actually has been here the whole time!) and even though the Fed talks about WANTING inflation . . . they really don’t. Inflation is something they claim is a positive, but given the amount of liquidity they pumped into the market, it is a ticking time bomb. In my previous inflation article that published on Feb 5, I went through the velocity of money and the caveats we face—so I won’t bore you with that here. As inflation gets “priced in,” investors will demand a higher payment to cover the weakening value of the currency. Simply said: a dollar today is worth less vs. a year from now, or 5 years from now. So if inflation is increasing, the value of the dollar is depreciating faster, and buyers of the debt will need to be compensated for the risk.

The Treasury holds auctions, which have a lot of metrics that the market looks at to deem if it was a strong (well attended) auction or a weak one. Think of a livestock auction or charity event: the more people bidding on an item, the higher the price goes. The more investors that look to buy will drive the bond price higher and the yield lower (price and yield are inverse to each other). There are other key metrics, such as indirect and direct bidders, and obviously the final yield on the security, but I will focus more on the health of the auctions and what has been permeating the system.

The most straightforward metric for looking at the health of an auction is the bid-to-cover ratio, or the total number of bids vs. the number of successful bids. Depending on duration (length of time in a security), the asset will garner a different level of interest and compensation. The bid-to-cover ratio in short duration securities has maintained over a “3” for the most part, but the back end of the curve (bonds maturing later) has seen a drop in activity. Typically, an auction that ends over “2” is deemed a successful auction, but trends of activity are important. While the numbers have gotten “weaker,” they remain in a safe range for now and could potentially see a spike in activity— but the sheer size and amount is making that less likely. But what is the cost to bring more people to the table? Answer: a higher yield or interest rate. “Sure, I will buy your 30-year debt . . . BUT . . . it will be at 2.5% and not 1.3%!” This is why we also need to look at the “average” bid submitted, because that is the price investors are willing to buy. And to no one’s surprise (or at least no one that holds my views on inflation), investors are demanding a higher interest rate to be compensated for risk and inflation, especially on the longer dated bonds. The U.S. is issuing more and more bonds, which is saturating the overall market. The sheer volume and inflation expectations are causing a bigger divergence to appear.

UST 8-Week Bill Bid-to-Cover Ratio

Bid-to-Cover Ratios of the 10/20/30 Year Treasuries

Another important aspect of yield impacts in the market is the “rate of change.” If yields are shifting rapidly, it means there is growing panic in the market as investors sprint to make changes to their portfolios. The MOVE index looks at bond volatility, which has accelerated to highs not seen since the beginning days of COVID. By looking at the Fed balance sheet, you can see the correlation that every time volatility rises, the Fed increases its intervention through various metrics—most recently, bond buying—to keep the markets calm. But the Fed balance sheet is now at an all-time high, and is already set to expand by at least $120B a month with rates at all-time lows. Without inflation, the Fed can argue We can still do more and expand loose monetary policy because we aren’t seeing it in the data.

Fed Balance Sheet vs BofA Move Index

The below chart looks at the yield curve and just how quickly things have shifted over the last month. The move higher in rates (green line) has also pulled up the “real rate,” or the amount you’ll make once you factor in inflation (or at least what CPI claims). As inflation becomes more apparent, the real yields will be pushed positive, in turn sending rates to new highs. The sheer size of the move should give investors and general market participants pause to reassess their underlying risk.

U.S. Treasury Yield Curve

You might be saying . . . “Well, can’t the Fed just buy more bonds?” Sure, they can! But when they buy bonds, they give the bank U.S. Dollars. We are already facing a spike in real-time and leading inflation indicators, and throwing more liquidity at the situation would exacerbate the growing problem. The Federal Reserve has been hit by the Law of Diminishing Returns, which simply means that it is costing more each time they look to stimulate the economy through monetary policy. The cost of stimulus goes up to create an equal reaction in the market. The Fed has been in a period of near constant expansion since 2008 through all forms of monetary policy. Back in 2008, we saw a quick expansion of $1.3T with steady support into the European crisis, causing an acceleration in activity from 2012 until 2014. The cracks started to form in Sept of 2019 when the REPO (repurchase agreement) market seized up and the Federal Reserve stepped in to protect rates. The Fed also unleashed liquidity on the market in March after several large firms went fully insolvent, creating the monetary support we see today. The size of monetary policy has shifted to the stratosphere with the Fed maintaining $120B a month in Treasury purchase over the next year.

So what happens when the U.S. Government INCREASES borrowing . . . who is going to be the buyer? The most common comment I’ve heard from investors and others is: Not to worry! The Fed can always be the buyer of last resort! But if inflation is accelerating and we are already awash with dollars, doesn’t that just add fuel to an ever-growing fire? This will limit the total purchases in the market, which means that other investors will have to pick up the slack in the rising number of bonds being issued. These investors also have A LOT of debt to choose from, as every country in the world tries to tap an exhausted bond market.

Federal Reserve Total Assets

The U.S. Government (and most governments around the world) are carrying an increasing deficit, but the U.S. is at the top of the list of that massive expansion when looking at fiscal policy. The global debt market hit a new all-time high of $281 Trillion, or 355% of global GDP. The amount of debt in the market means that ANY change in rates has an exponential impact due to the sheer size. Many governments issue new debt to replace old debt, but as interest rates rise, it costs more money to pay off the debt. Due to COVID19, many of these governments have INCREASED their borrowing to stimulate the economy. The problem is, many of these governments have been trying to stimulate the economy for YEARS . . . essentially since 2008. So did the financial crisis ever really end?

Another problem rarely talked about is the amount of cash going into money market accounts or the overnight market. Competition is generated for short-term debt that the Fed buys in fistfuls, as more demand chases a shrinking pool of assets. This creates a steepening of the yield curve and underlying problems in short duration.

You might look at current rates in the below chart and think: I get what you are saying, but we are still below historic norms and don’t have much to worry about. Sure, the move was sharp and volatile, but things will calm down! But that is ignoring the amount of new debt coming to market, the limited buyers showing up, and the inflation indicators running red hot.

U.S. 10 Year Treasury Metrics

The first chart in the article shows the different rounds of stimulus and how the one in congress now doubles the amount of fiscal support in the market. Some economists are questioning the size of the fiscal stimulus at $1.9T because there has been recovery in some key metrics. Should the stimulus be closer to $900B, or should the Fed just start to “taper” monetary policy to allow the Biden stimulus bill to work its magic? The measure being used is the output gap, or difference between actual and potential GDP, which shows the excess capacity is smaller in the U.S. (meaning we don’t need a stimulus bill that large).

There are some good reasons why the Fed can’t taper—they would leave even more paper in the market and take away a key buyer! The Federal Reserve owns over half of the U.S.’s current outstanding debt, followed by Japan and China. Foreign buyers have been less active—putting more pressure on other holders, ranging across different direct and indirect buyers. China has been trying to reduce their Treasury holdings, pulling forward USD to increase near-term collateral against rising bad debt expense and replenish foreign reserves. They have also wanted to reduce exposure to the U.S. dollar and banking system to mitigate impacts of potential sanctions and other restrictions placed on them as the U.S.-China relationship deteriorates (that is next week’s article).

U.S. Debt Ownership Metrics

There is another key reason the Fed can’t start to ease: TAPER TANTRUM!!! The market is worse than my overtired, sick toddler. This panic in rates happened WITHOUT even mentioning a taper. Anyone that sees the headlines from Fed governors or reads the very exciting minutes—not a single soul has made the slightest hint of a taper. Most of the voting members remain extremely accommodative (or “Dovish” as it is called in market lingo). For those old enough to remember the 2013 taper tantrum, it created a rapid rise in yields and caused the Fed to reverse course and feed the junkie more drugs (liquidity). The recent move is happening without even a HINT of a Fed changing course . . .

10 Year Yield vs 2 Year Yield from Robin Brooks of IIF

“The U.S. Treasury Department said Wednesday the deficit from October through December totaled a record $573 billion, a 61% increase from the same period a year earlier. Federal outlays rose 18%, to $1.4 trillion, driven higher primarily by automatic safety-net spending such as jobless benefits, nutrition assistance and health care. Total receipts held steady, at $803 billion, the Treasury said.”[1] By looking at the below chart, the U.S. has been running an expanding deficit for a very very long time with no end in sight. The common view is: Not to worry! We will grow out of it! But doesn’t debt weigh on future growth because . . . you actually have to pay off your debts? How can you invest if you have a rising interest expense?

Even as interest rates have fallen, the federal government’s interest expense has remained at historic levels because of the increase in borrowing. A common view has been that cheap rates will be key to keep our payments low, but we have seen a ferocious move higher that will only see costs go up as we roll old debt and issue new to cover our stimulus.

The speed of the correction has caught some by surprise, but it also has implications for the market. The U.S. Treasury 10-year is now paying more vs. the S&P 500 dividend, which could pull money out of the riskier equity asset and into the “safe haven” of the Treasury. The rise in rates increases the cost of companies’ borrowing, sends mortgage rates higher, and most importantly in today’s market, increases margin costs. Many retail investors are utilizing margin accounts and as the cost of borrowing goes up, so does your cost to trade on margin. A continuation of the bond sell-off will reverberate through the system, and because the size of the bubble is so massive, a small move impacts things exponentially.

S&P 500 Dividend Yield vs U.S. 10 Year Treasury

We have been in a world stuffed with liquidity and central bank easing since 2008, which is now setting off a chain reaction of rising rates. Central banks need perpetual motion to keep the merry-go-round operation and a buyer of last resort . . . they are losing both. The game isn’t over yet, but we are seeing the implications of what a bubble in everything looks like, and the fragile nature of the underlying economics. We are nearing the end of the circus: CHAIR POWELL: “[Lower interest rates] make it cheaper to borrow, they do raise asset prices, including the value of your home. But for people who are really just relying on their bank savings account earnings, you’re not going to benefit from low interest rates.” The activity from the Fed has driven inequality to all new heights, with wage compression everywhere and asset prices flying. People have scrambled to get involved, but at the risk of losing everything in the GameStops and other meme stocks. The coil continues to get wound and the spring is loaded. Bubbles have been inflated around the world, and because we are all so interconnected, the dominos are in place. A failed auction is just around the corner. That could be a bid-to-cover below 2 approaching 1, or a straight-up failed auction, where a key country fails to sell the full amount of debt being offered. This means no more spending . . . this means austerity . . . higher taxes . . . it means money is no longer free. The party’s over!

[1] https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-budget-gap-rose-61-in-first-quarter-of-fiscal-2021-11610564411